[Image 1 / 152]

(Binding)

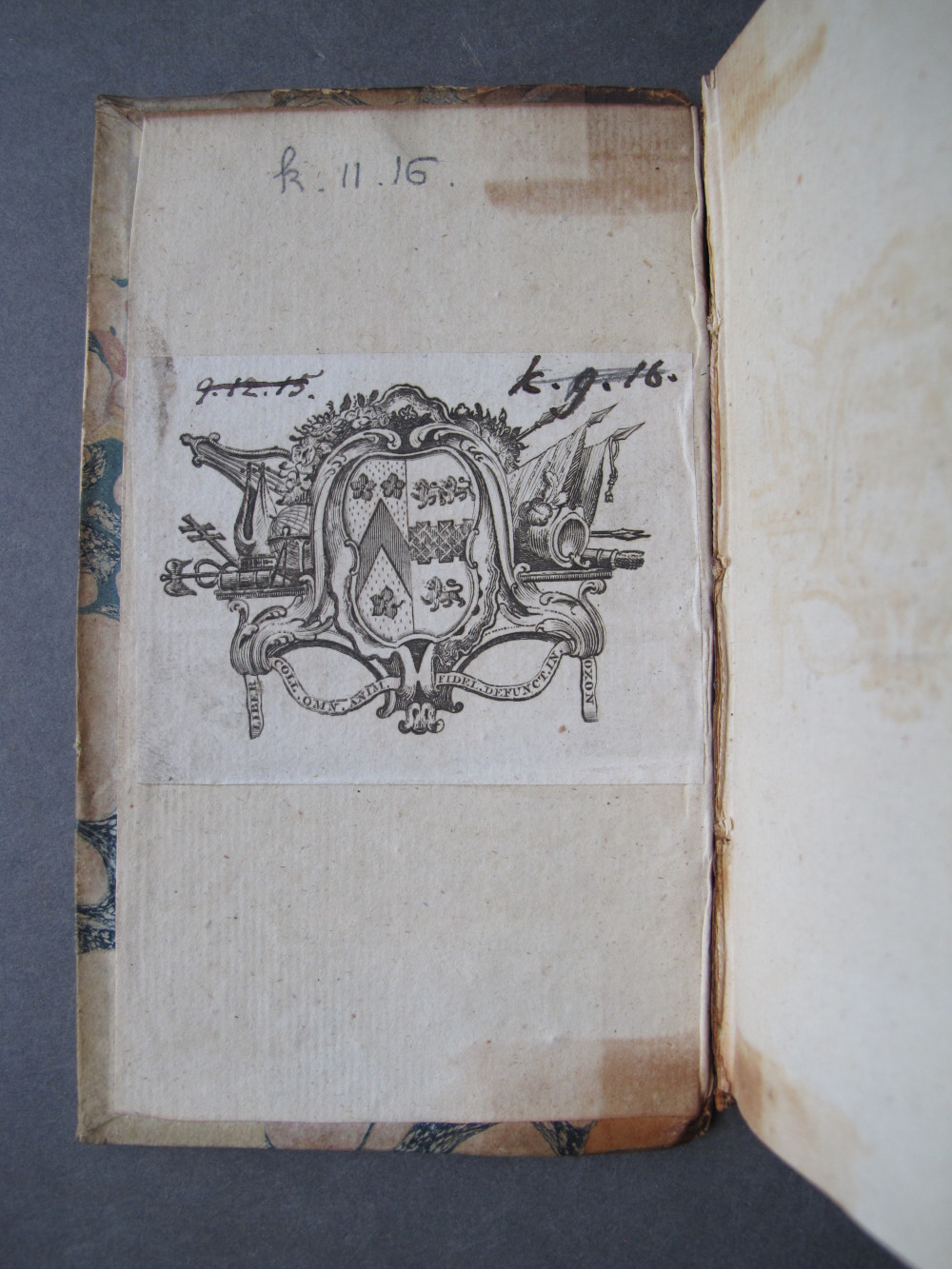

[Image 2 / 152]

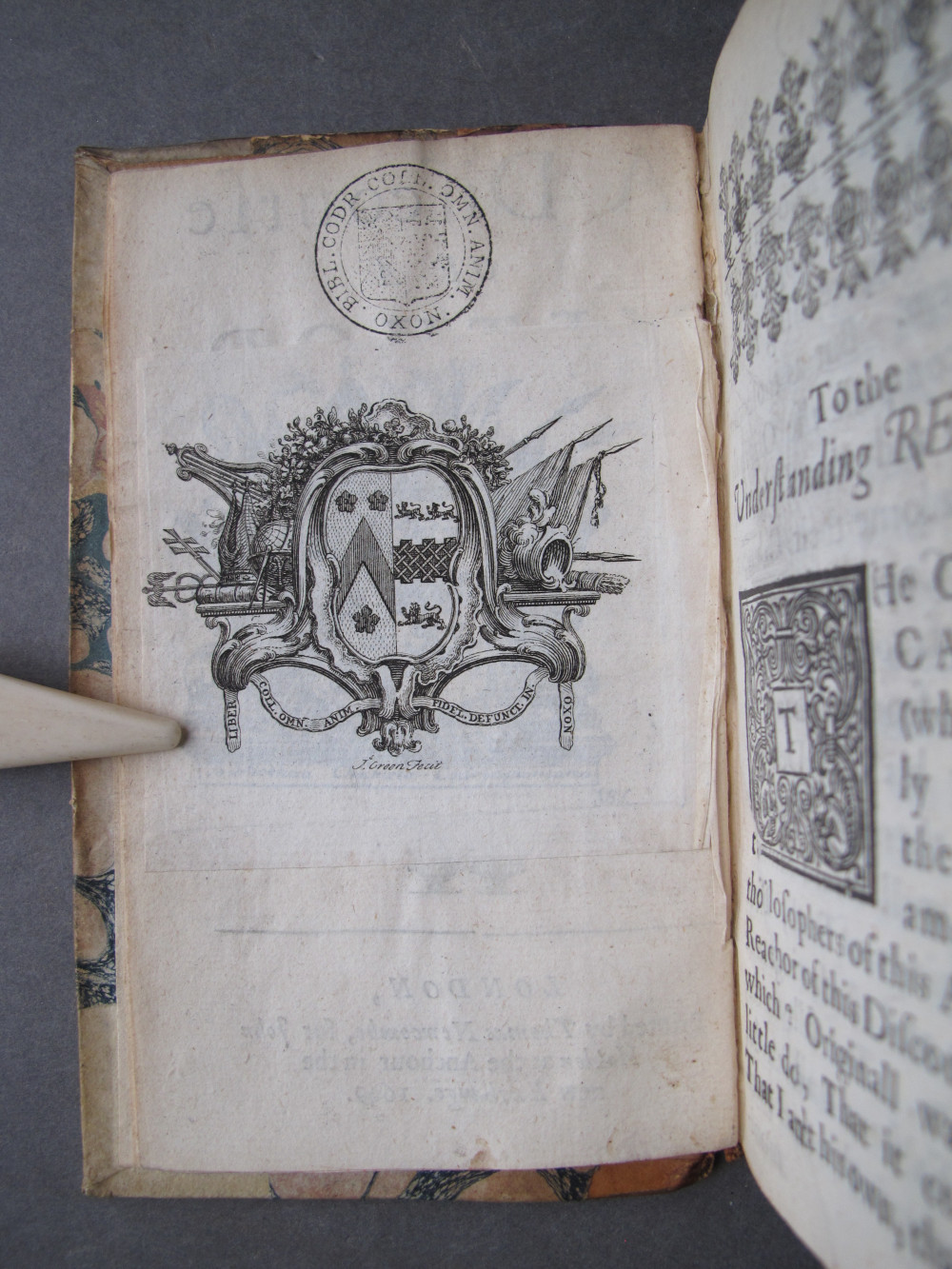

(Bookplate)

[Image 3 / 152]

[Image 4 / 152]

[Image 5 / 152]

[Image 6 / 152]

[Image 7 / 152]

[Image 8 / 152]

[Image 9 / 152]

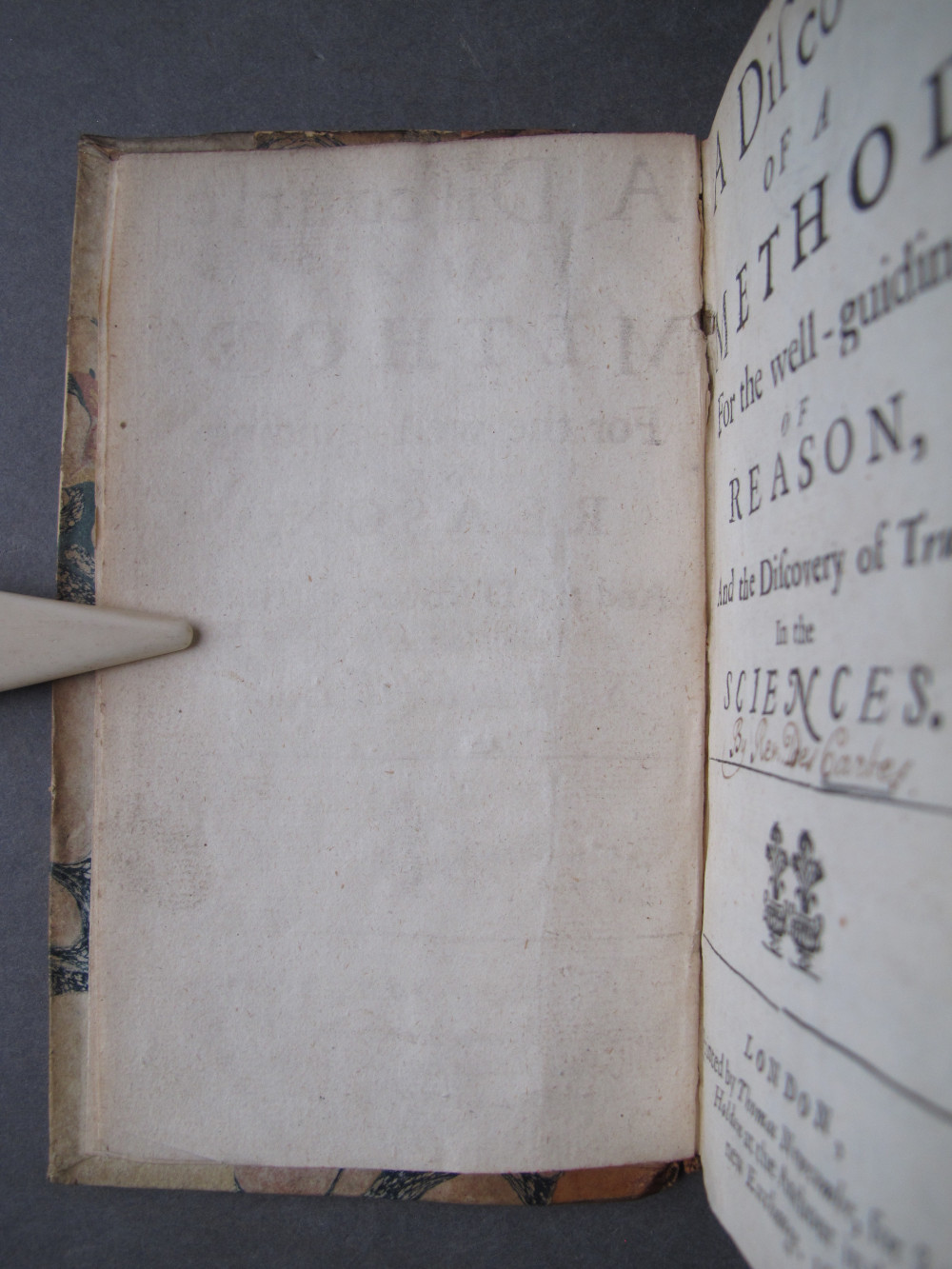

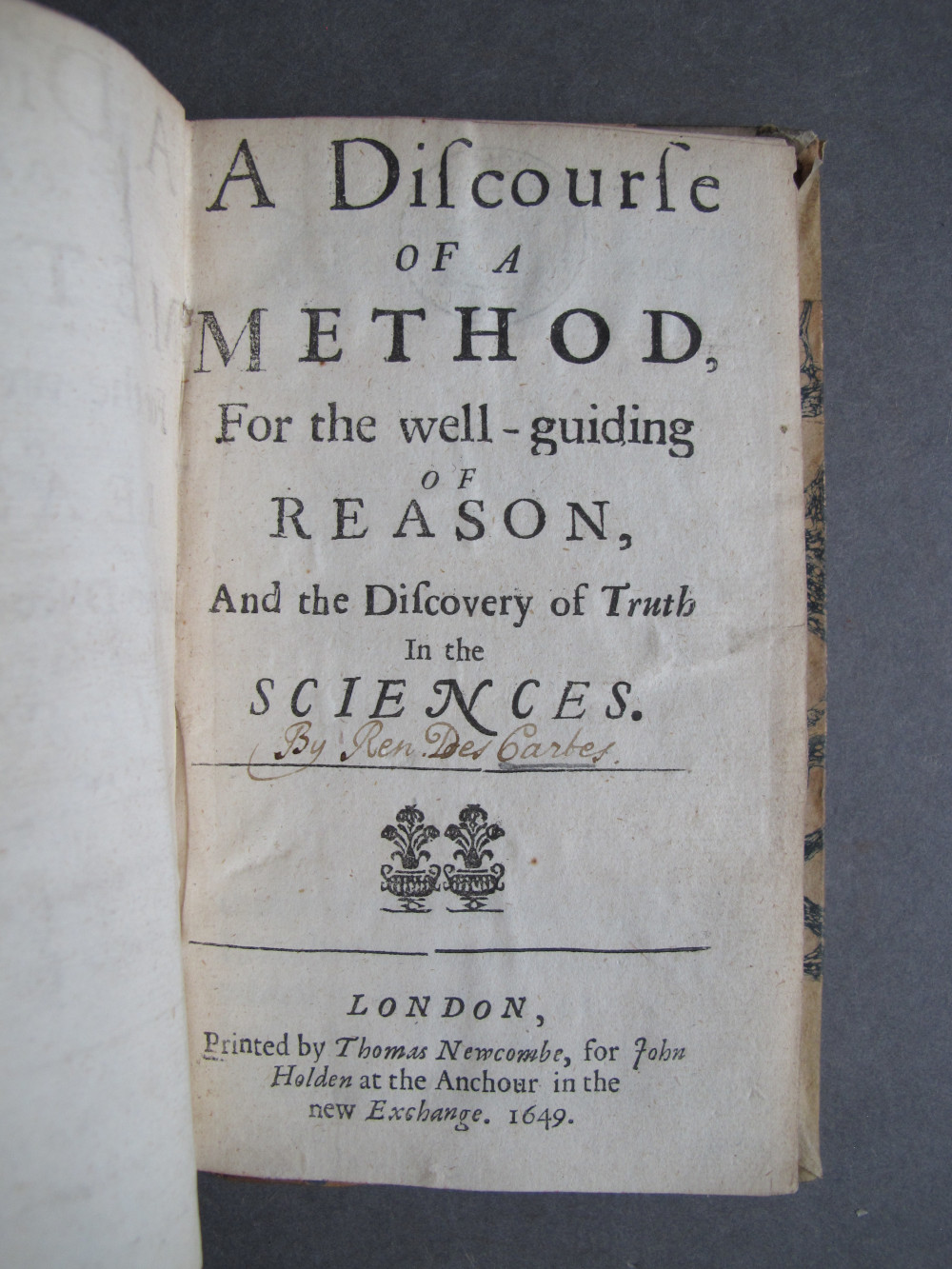

(Title Page)

[Image 10 / 152]

(Bookplate)

[Image 11 / 152]

([Page i])

![[Page i], text:

To the

Understanding READER.

THe Great DES

CARTES

(who may just-

ly challenge

the first place

amongst the

[phi]losophers of this Age) is the

[aut]hor of this Discourse; which

Originall was so well

, That it could be no

t his own, that his Name

was](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[011]_[p_i].JPG)

[Image 12 / 152]

([Page ii])

![[Page ii], text:

()

was not affic'd to it: I need say

no more either of Him or It;

He is best made known by Him-

self, and his Writings want no-

thing but thy reading to com-

mend them. But as those who

cannot compasse the Originals

of Titian and Van-Dyke, are

glad to adorne their Cabinets

with the Copies of them; So

be pleased favourably to receive

is Picture from my hand, co-

pied after his own Designe:

You may therein observe the

lines of a well form'd Minde

The hightnings of Truth, T

sweetnings and shadowings

Probabilities, The falls

depths of Falshood; all

serve to perfect this](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[012]_[p_ii].JPG)

[Image 13 / 152]

([Page iii])

![[Page iii], text:

()

piece. Now although my af-

ter-draught be rude and unpo-

lished, and that perhaps I have

touch'd it too boldly, The

thoughts of so clear a Minde,

being so extremely fine, That

as the choisest words are too

grosse, and fall short fully to

expresse such sublime Notions;

So it cannot be, but being trans-

vested, it must necessarily lose

very much of its native Lustre:

Nay, although I am conscious

(notwithstanding the care I have

taken neither to wrong the Au-

thours Sense, nor offend the

Readers Ear) of many escapes

which I have made; yet I so

little doubt of being excused,

That I am confident, my endea-

vour](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[013]_[p_iii].JPG)

[Image 14 / 152]

([Page iv])

![[Page iv], text:

()

vour cannot but be gratefull to

all Lovers of Learning; for

whose benefit I have English-

ed, and to whom I addresse

this Essay, which contains a

Method, by the Rules whereof

we may Shape our better part,

Rectifie or Reason, Form our

Manners and Square our Acti-

ons, Adorn our Mindes, and

making a diligent Enquiry into

Nature, wee may attain to the

Knowledge of the Truth, which

is the most desirable union in

the World.

Our Authour also invites

all letterd men to his assistance

in the prosecution of this Search;

That for the good of Mankinde,

They would practise and com-

muni-](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[014]_[p_iv].JPG)

[Image 15 / 152]

([Page v])

![[Page v], text:

()

municate Experiments, for the

use of all those who labour for

the perfection of Arts and Sci-

ences: Every man now being

obliged to the furtherance of

so beneficiall an Undertaking,

I could not but lend my hand

to open the Curtain, and disco-

ver this New Model of Philoso-

phy; which I now publish, nei-

ther to humour the present, nor

disgust former times; but rather

that it may serve for an innocent

Divertisement to those, who

would rather Reform them-

selves, then the rest of the world;

and who, having the same seeds

and grounds, and knowing That

there is nothing New under the

Sun; That Novelty isbut Ob-

livion,](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[015]_[p_v].JPG)

[Image 16 / 152]

([Page vi])

![[Page vi], text:

()

livion, and that Knowledge is

but Remembrance, will study to

finde out in themselves, and re-

store to Posterity those lost Arts,

which render Antiquity so ve-

nerable; and strive (if it be pos-

sible) to go beyond them in o-

ther things, as well as Time:

Who minde not those things

which are above, beyond, or

without them; but would ra-

ther limit their desires by their

power, then change the Course

of Nature; Who seek the

knowledge, and labour for the

Conquest of themselves; Who

have Vertue enough to make

their own Fortune; And who

prefer the Culture of the Minde

before the Adorning of the Bo-

dy;](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[016]_[p_vi].JPG)

[Image 17 / 152]

([Page vii])

![[Page vii], text:

()

dy, To such as these I present

this Discourse (whose pardon

I beg, for having so long de-

tain'd them from so desirable a

Conversation;) and conclude

with this Advice of the Divine

Plato:

Cogita in te, praeter Animum,

nihil esse mirabile.](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[017]_[p_vii].JPG)

[Image 18 / 152]

([Page viii])

![[Page viii] (no text)](./k_11_16_images/k_11_16_[018]_[p_viii].JPG)

[Image 19 / 152]

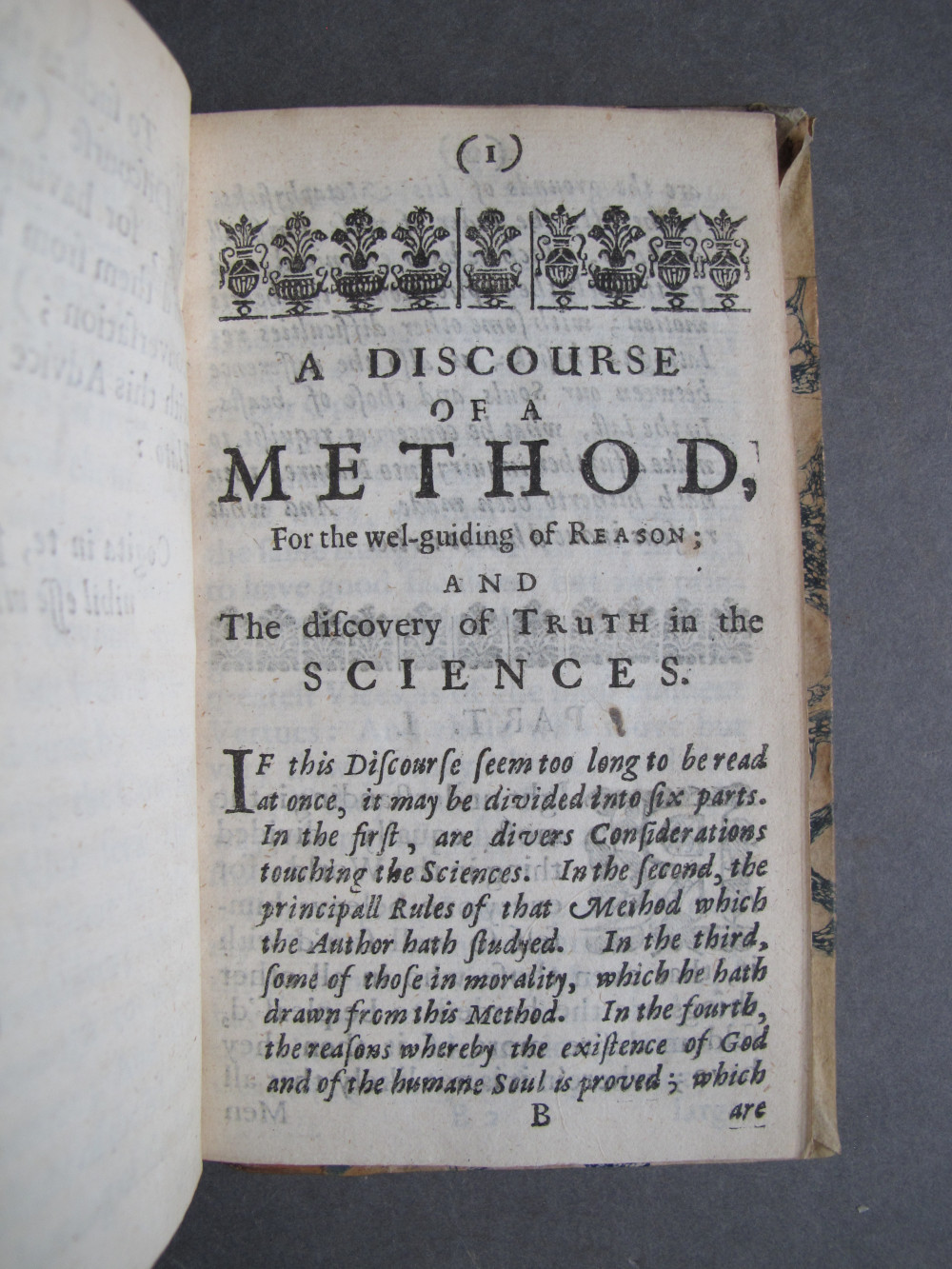

(Page 1)

[Image 20 / 152]

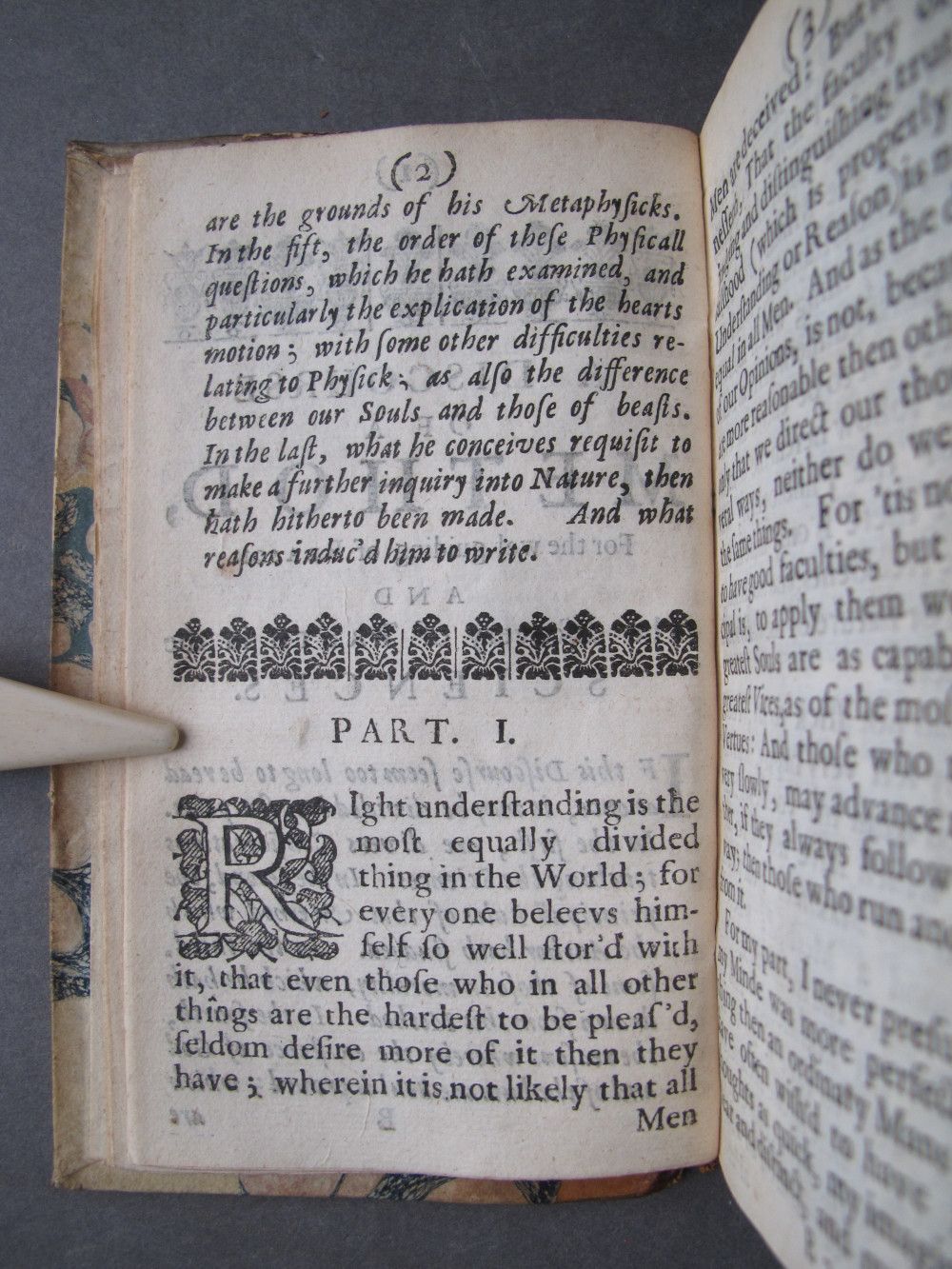

(Page 2)

[Image 21 / 152]

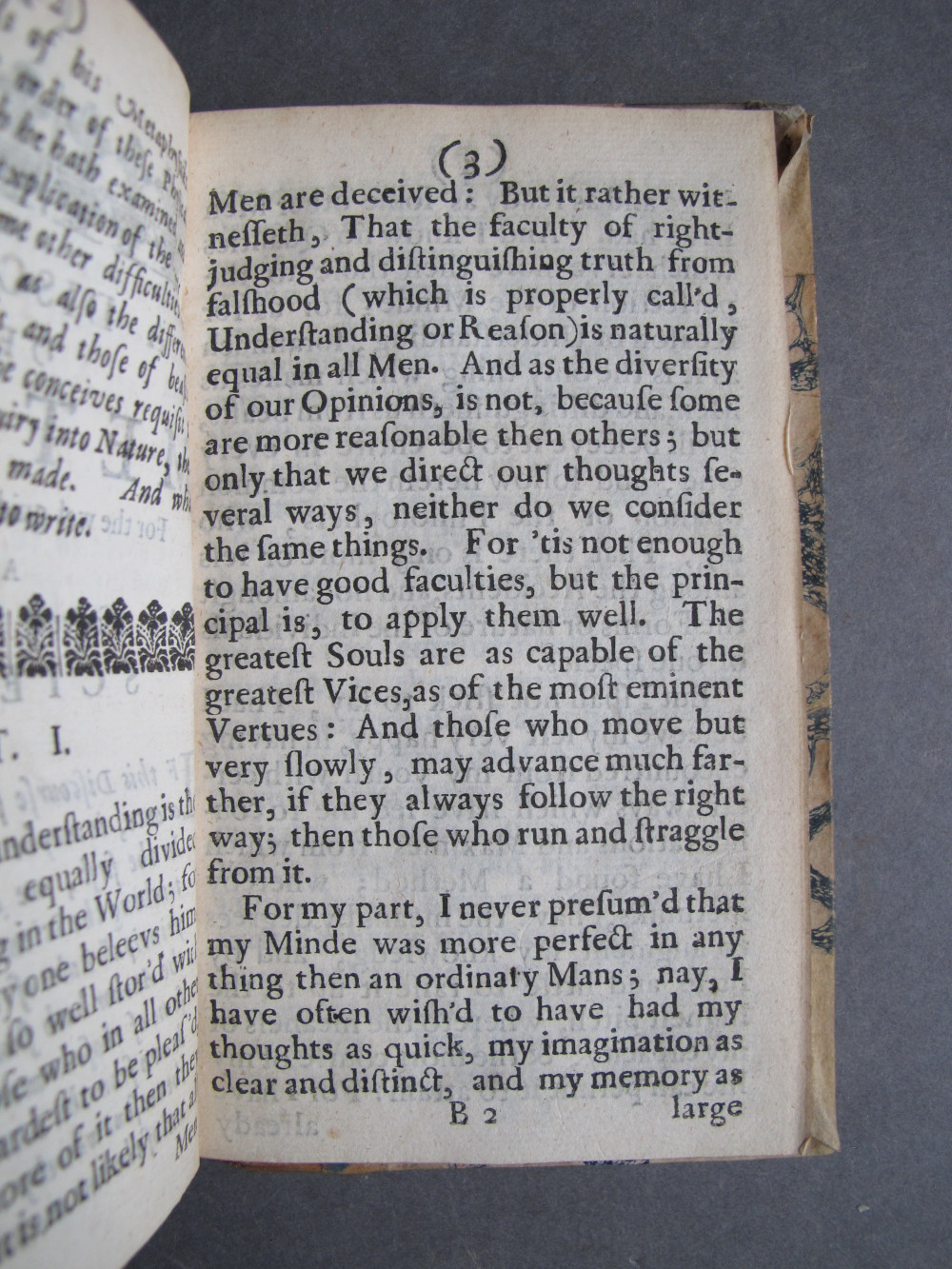

(Page 3)

[Image 22 / 152]

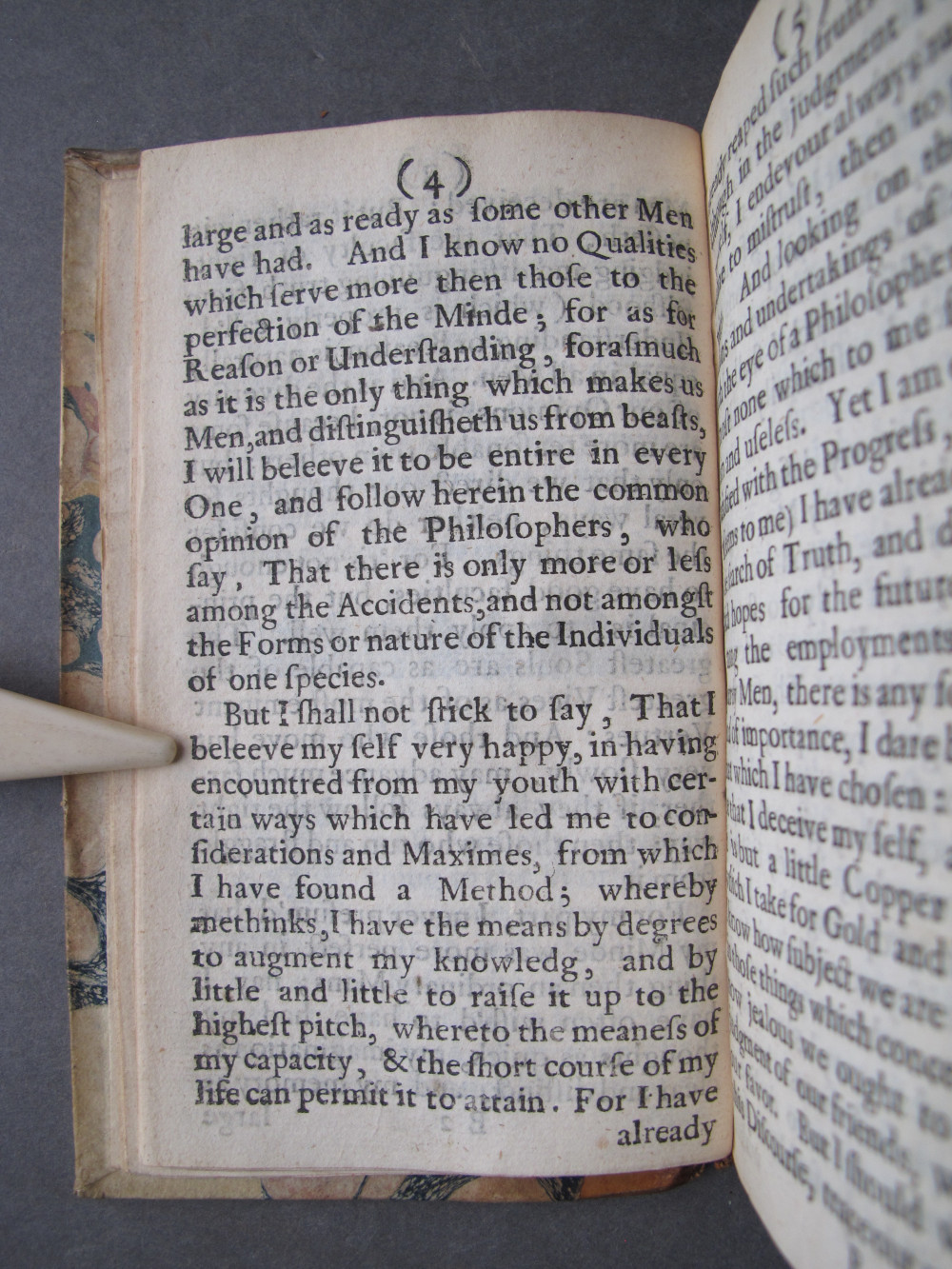

(Page 4)

[Image 23 / 152]

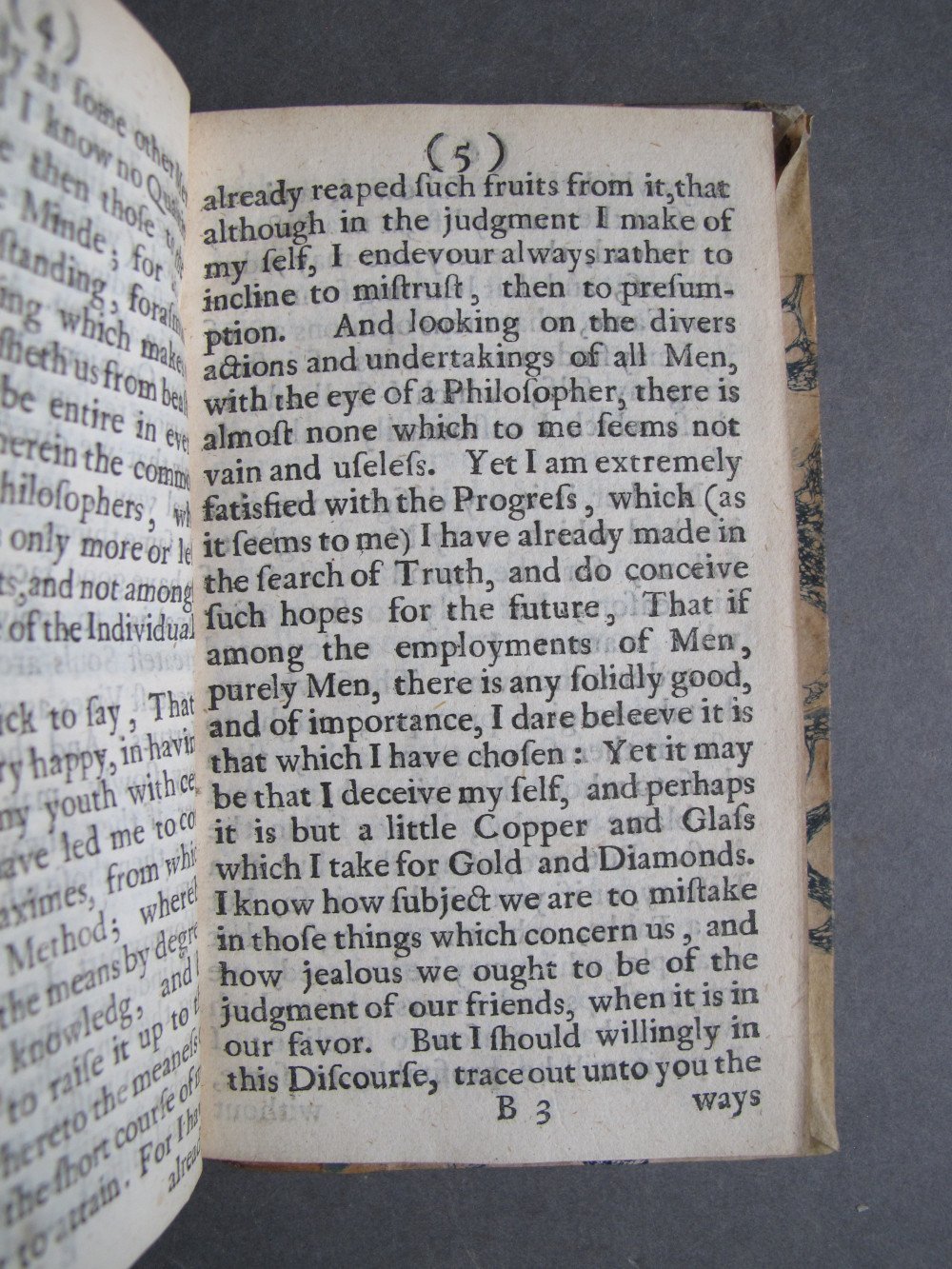

(Page 5)

[Image 24 / 152]

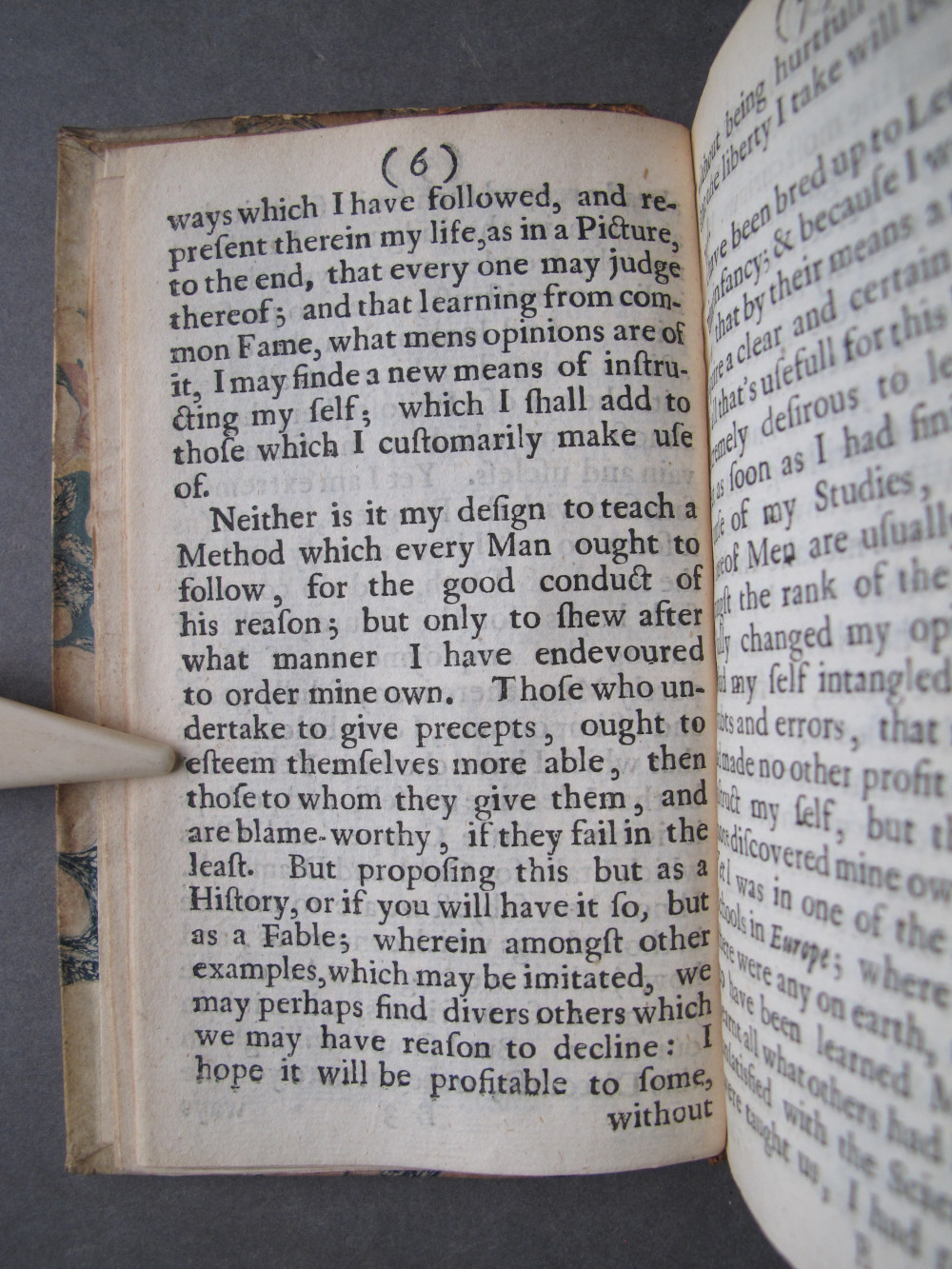

(Page 6)

[Image 25 / 152]

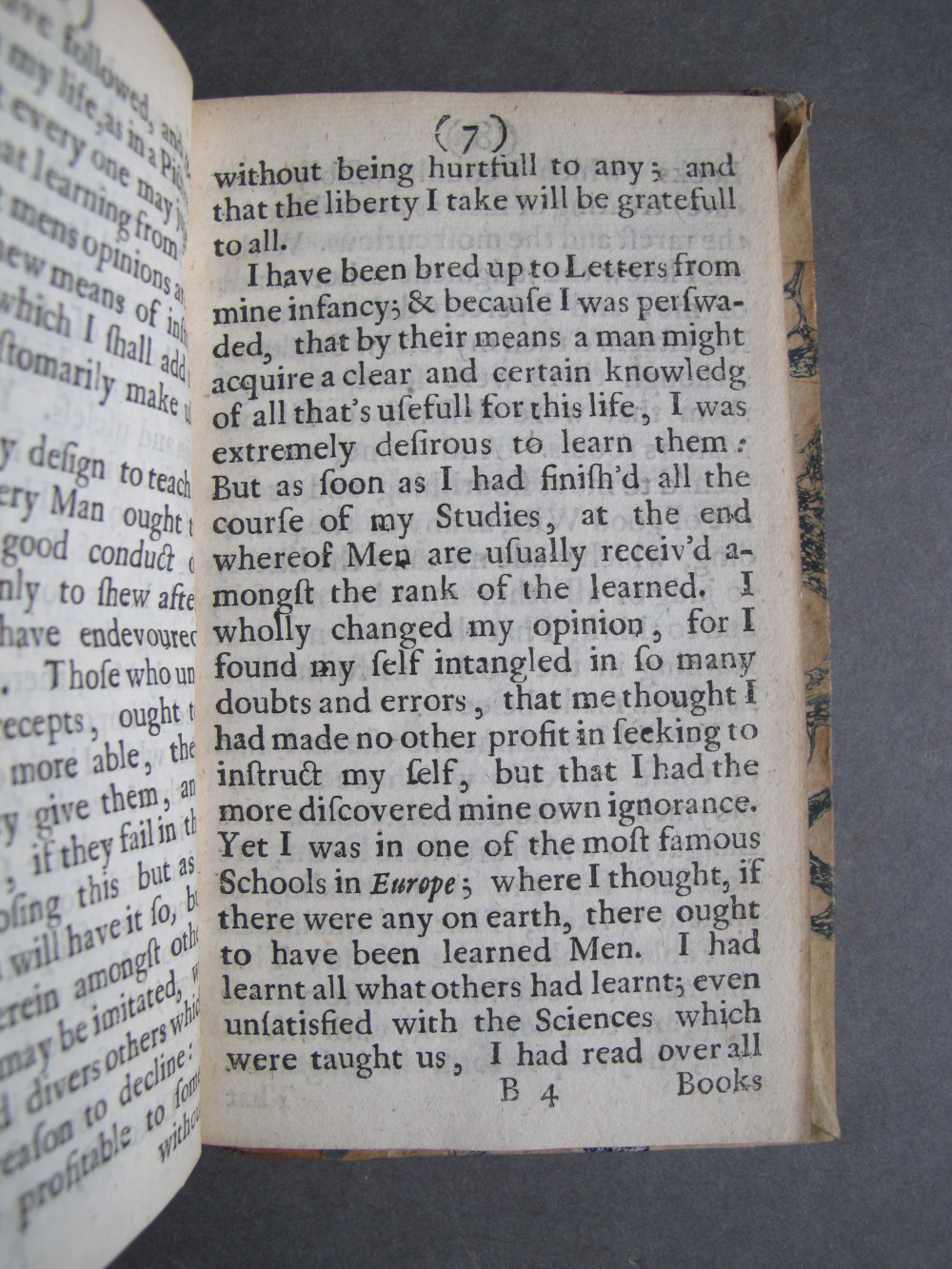

(Page 7)

[Image 26 / 152]

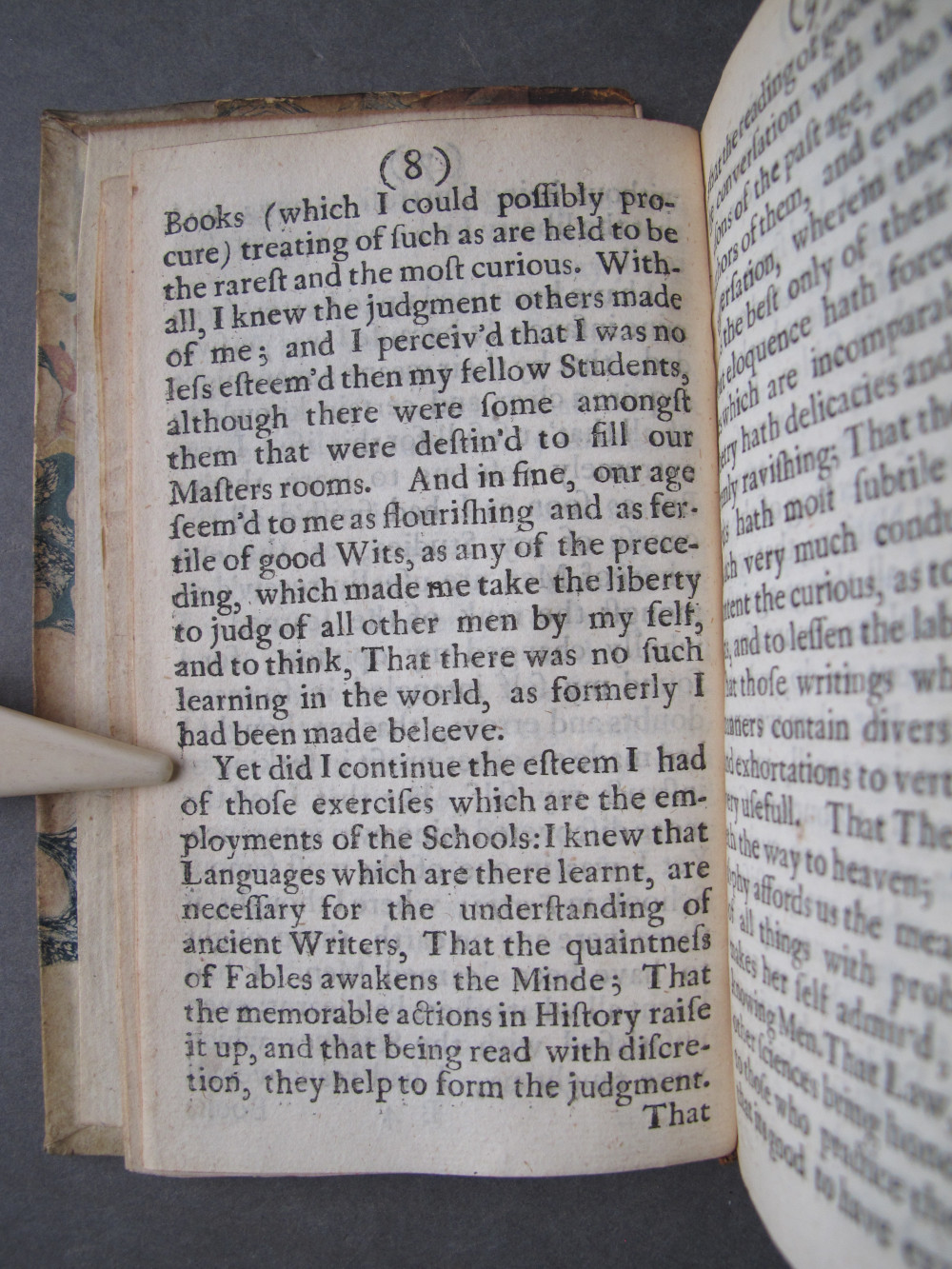

(Page 8)

[Image 27 / 152]

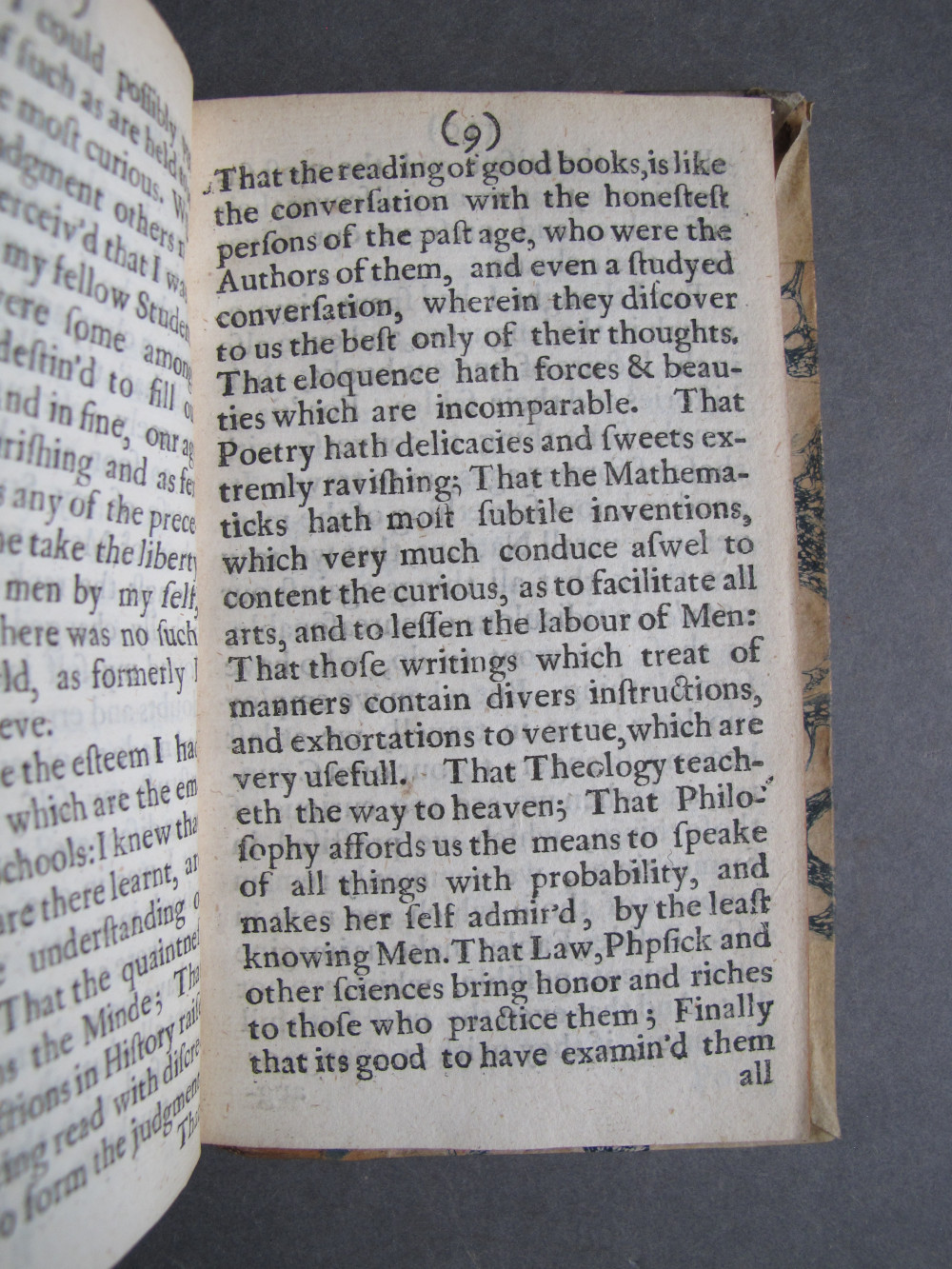

(Page 9)

[Image 28 / 152]

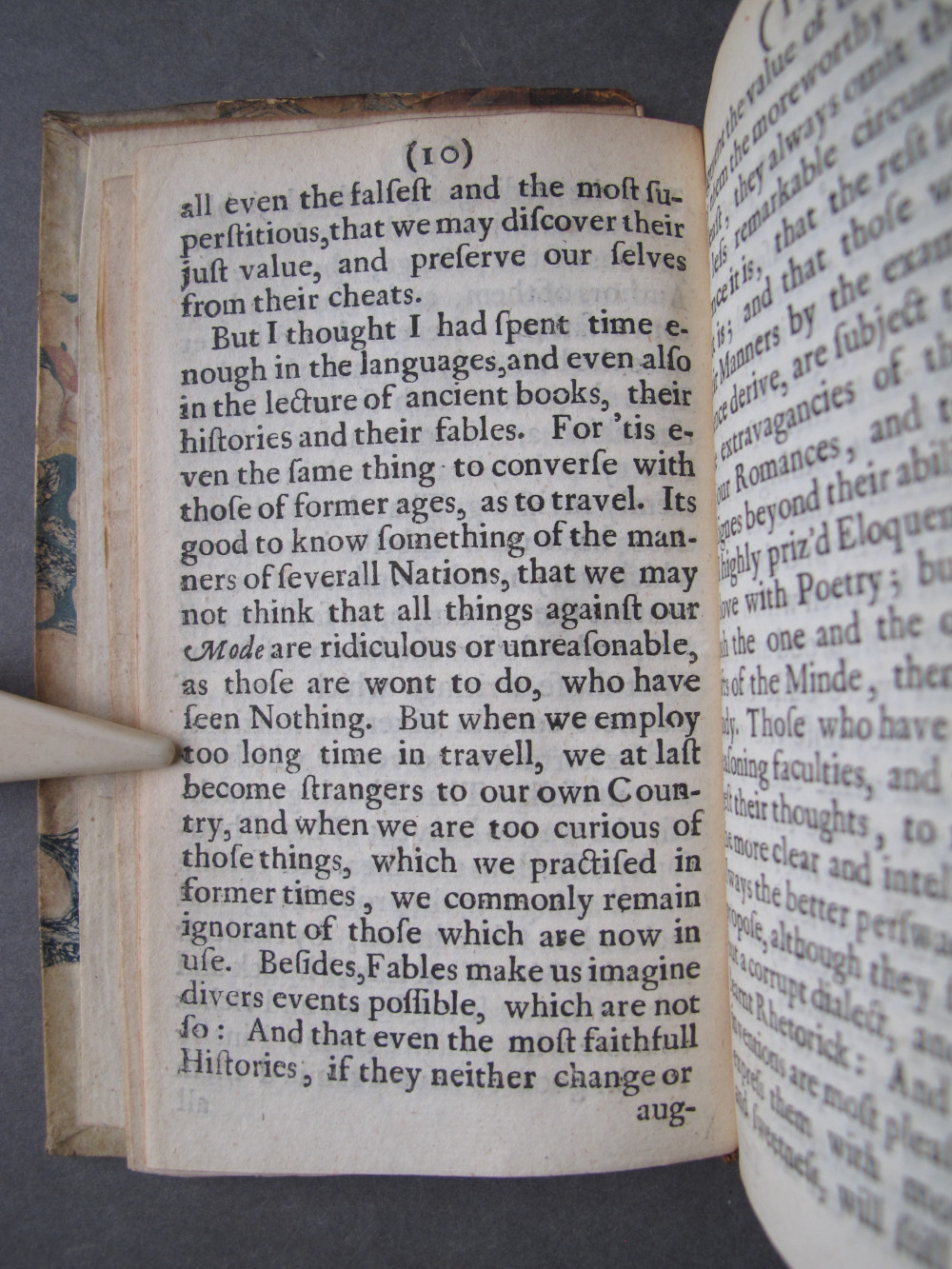

(Page 10)

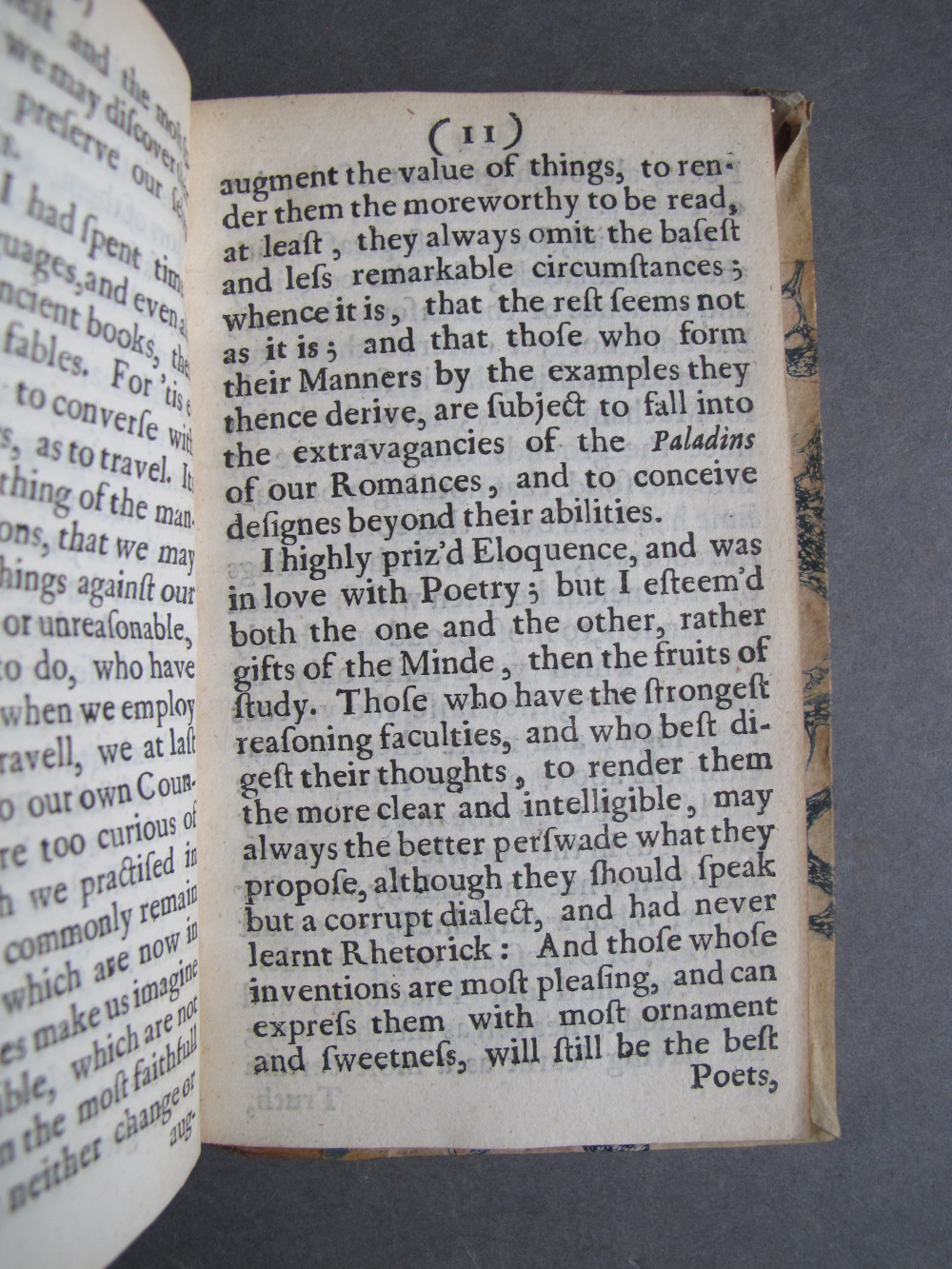

[Image 29 / 152]

(Page 11)

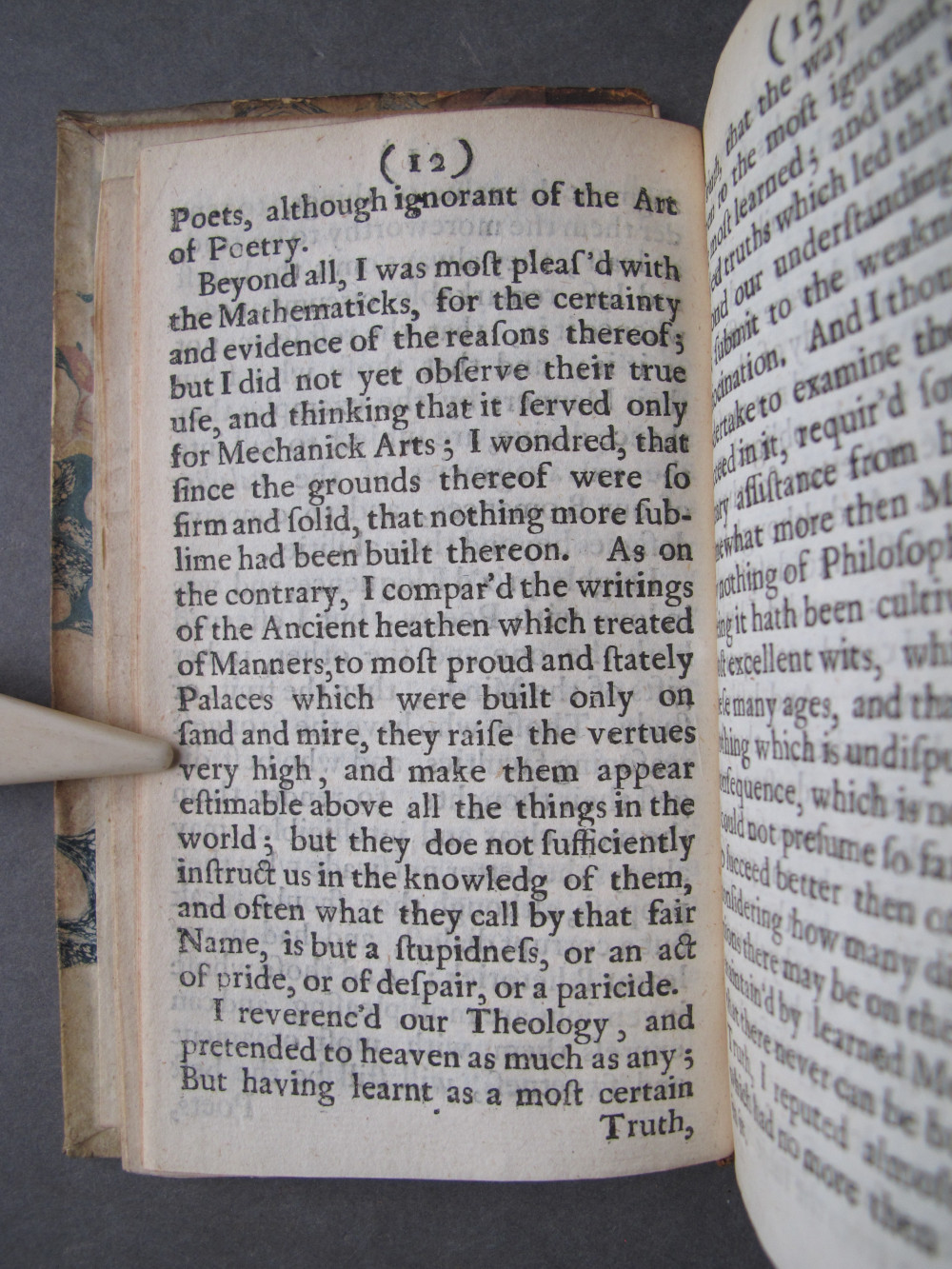

[Image 30 / 152]

(Page 12)

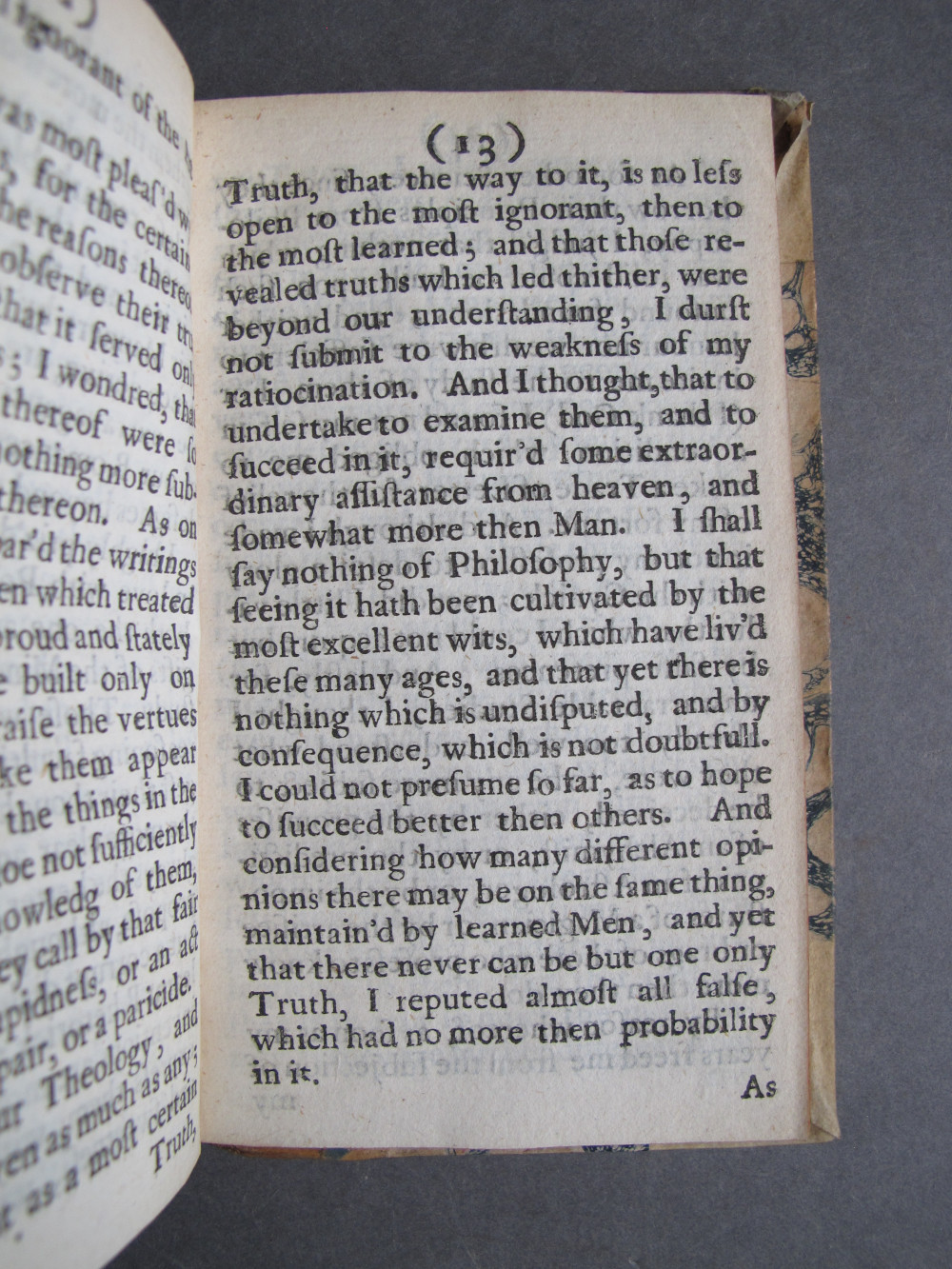

[Image 31 / 152]

(Page 13)

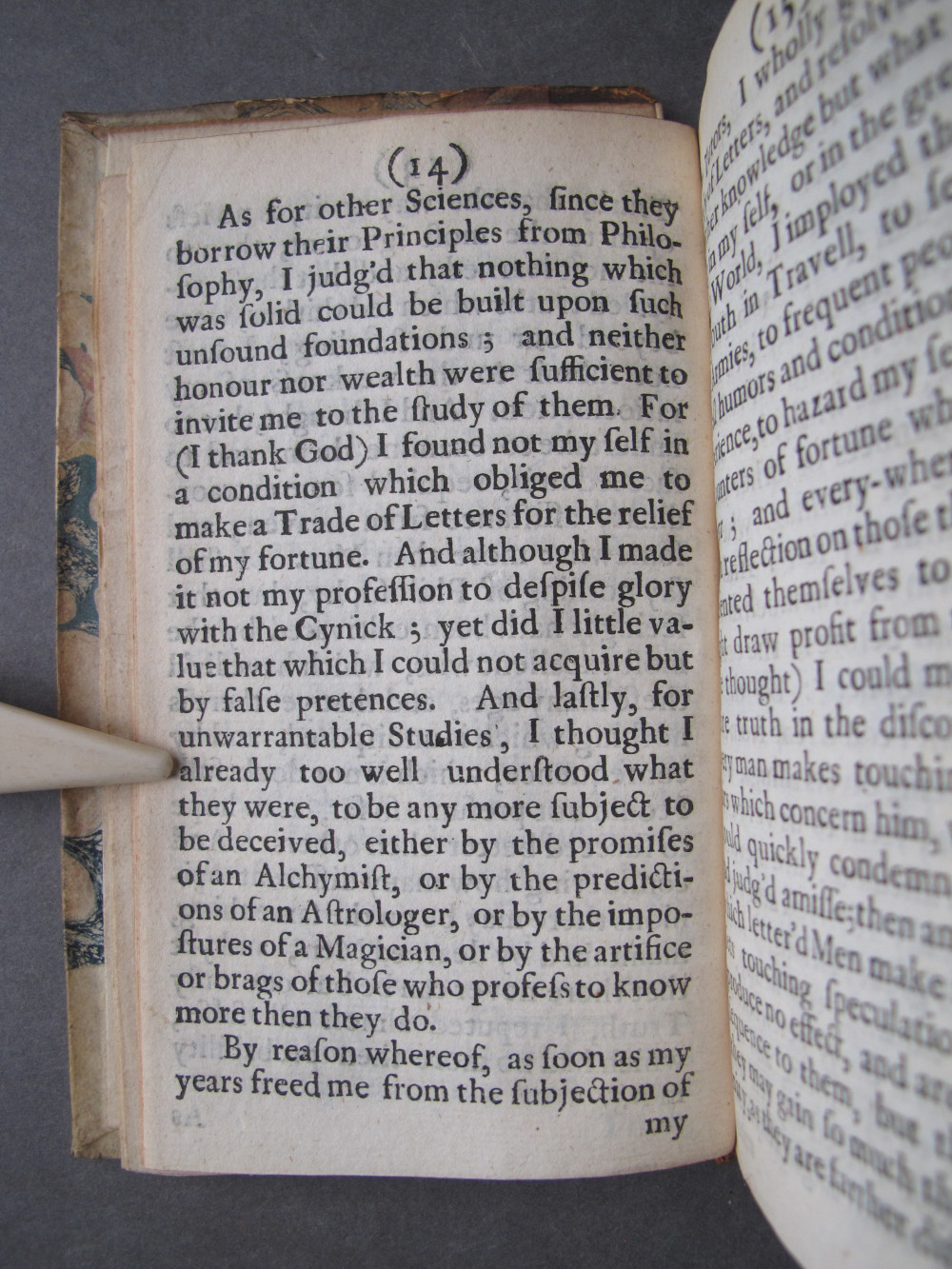

[Image 32 / 152]

(Page 14)

[Image 33 / 152]

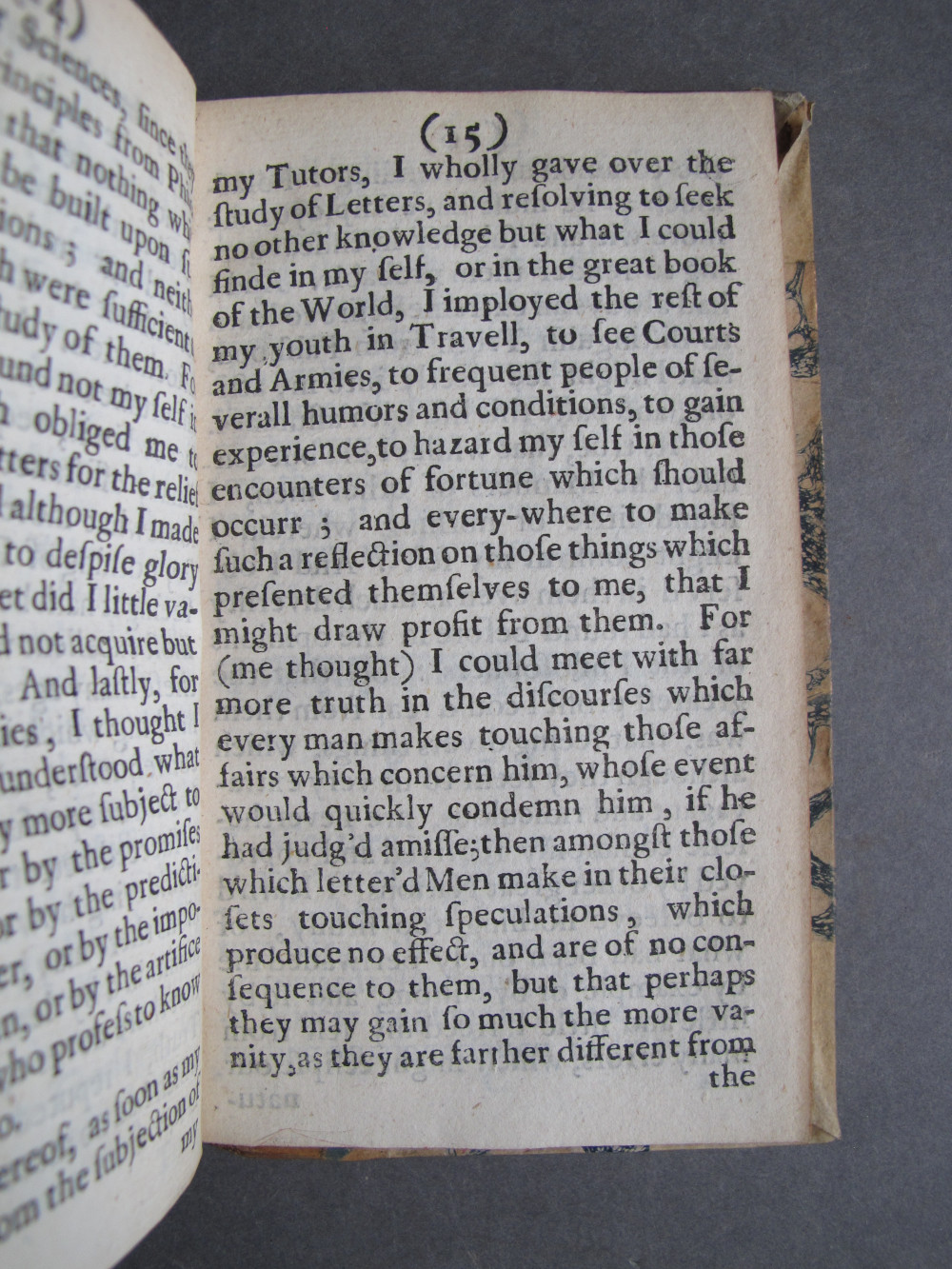

(Page 15)

[Image 34 / 152]

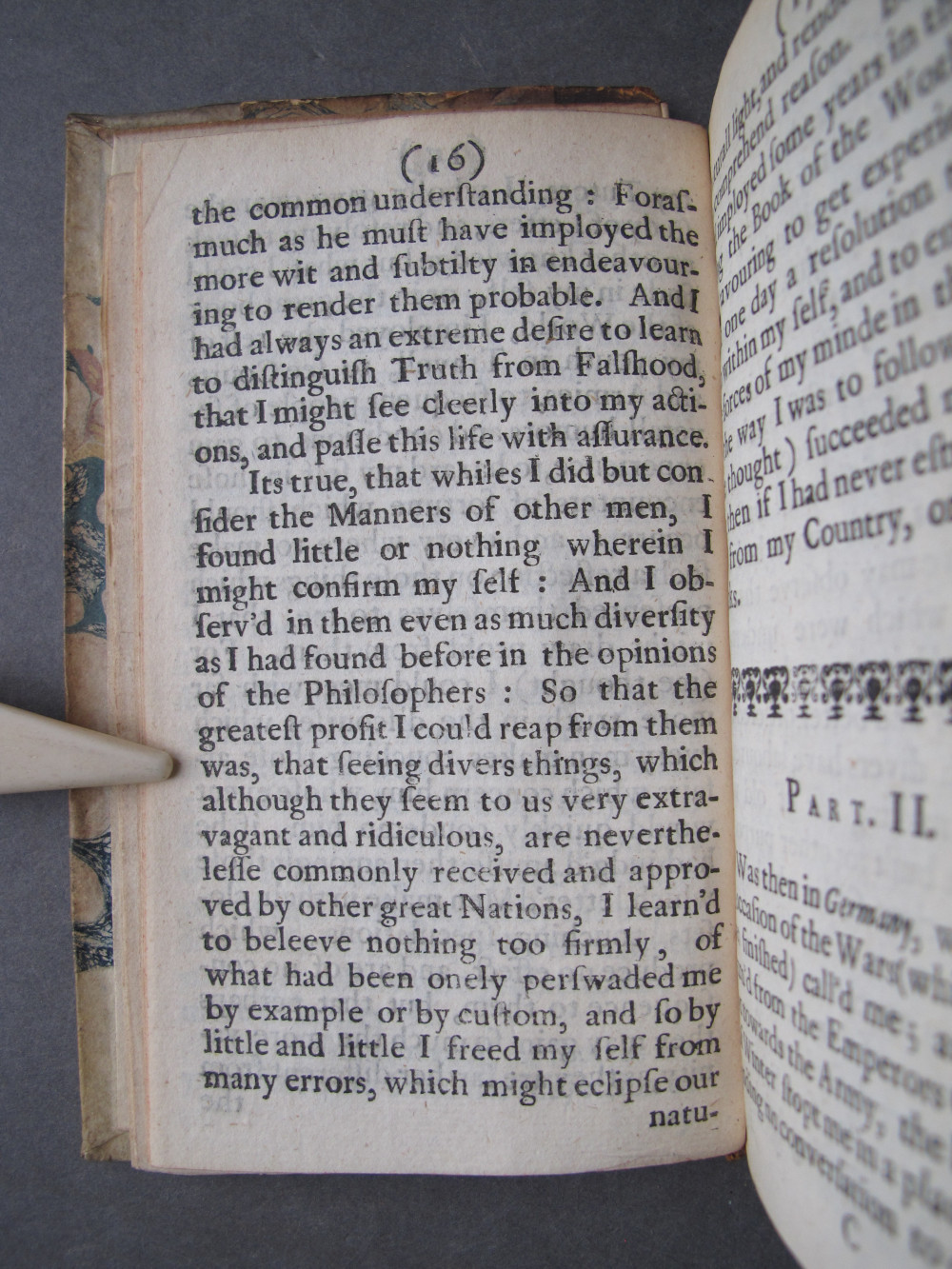

(Page 16)

[Image 35 / 152]

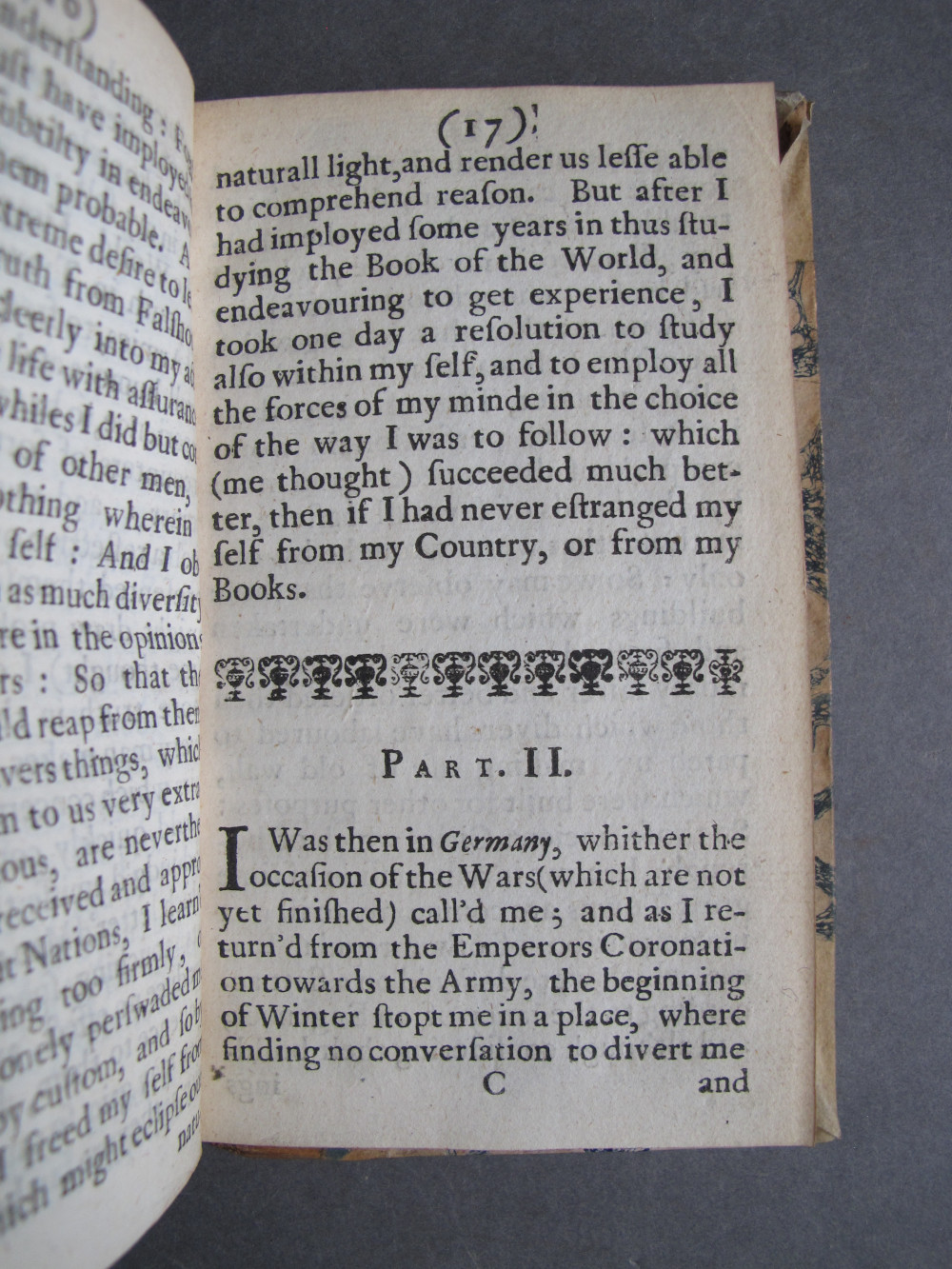

(Page 17)

[Image 36 / 152]

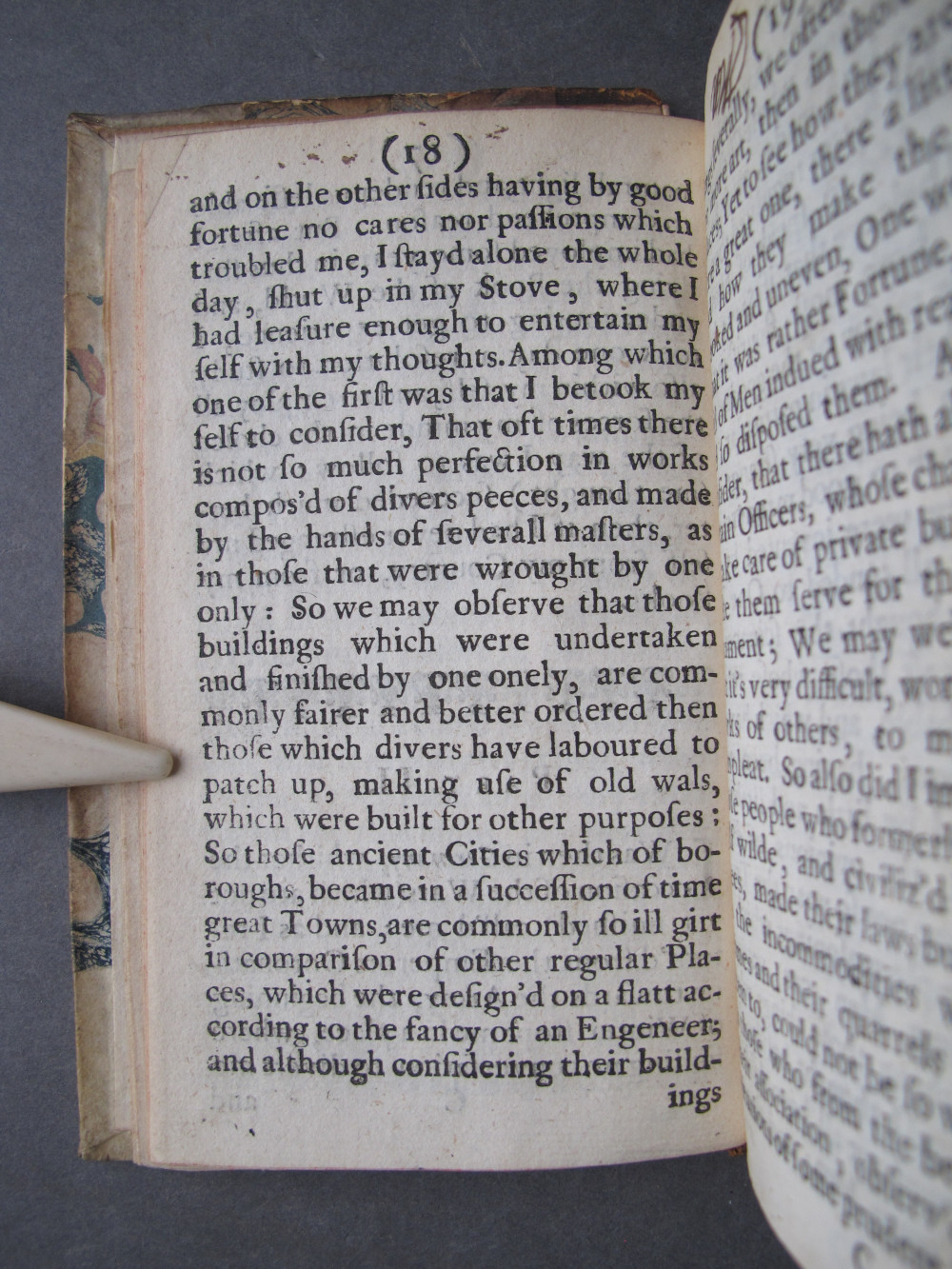

(Page 18)

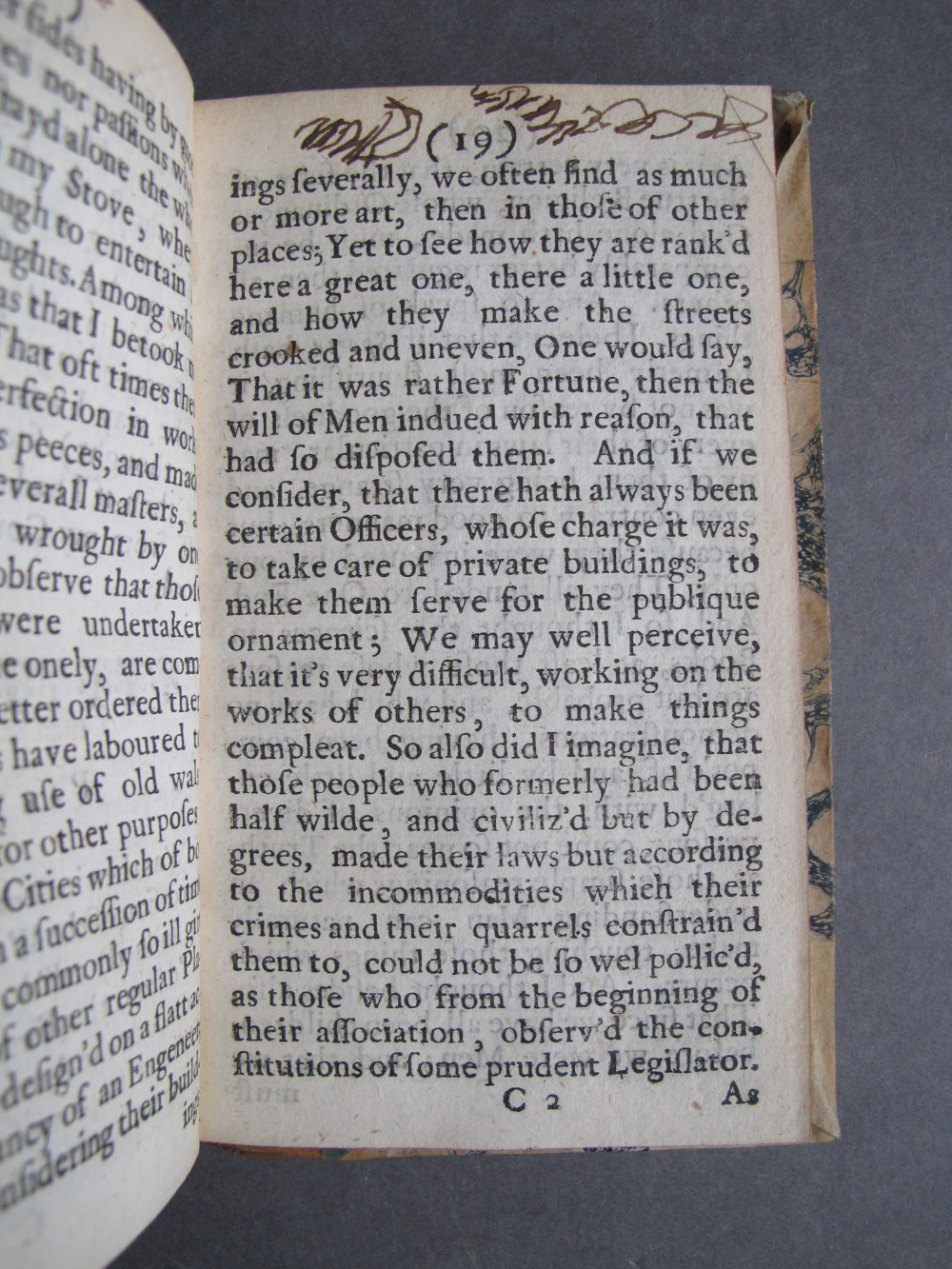

[Image 37 / 152]

(Page 19)

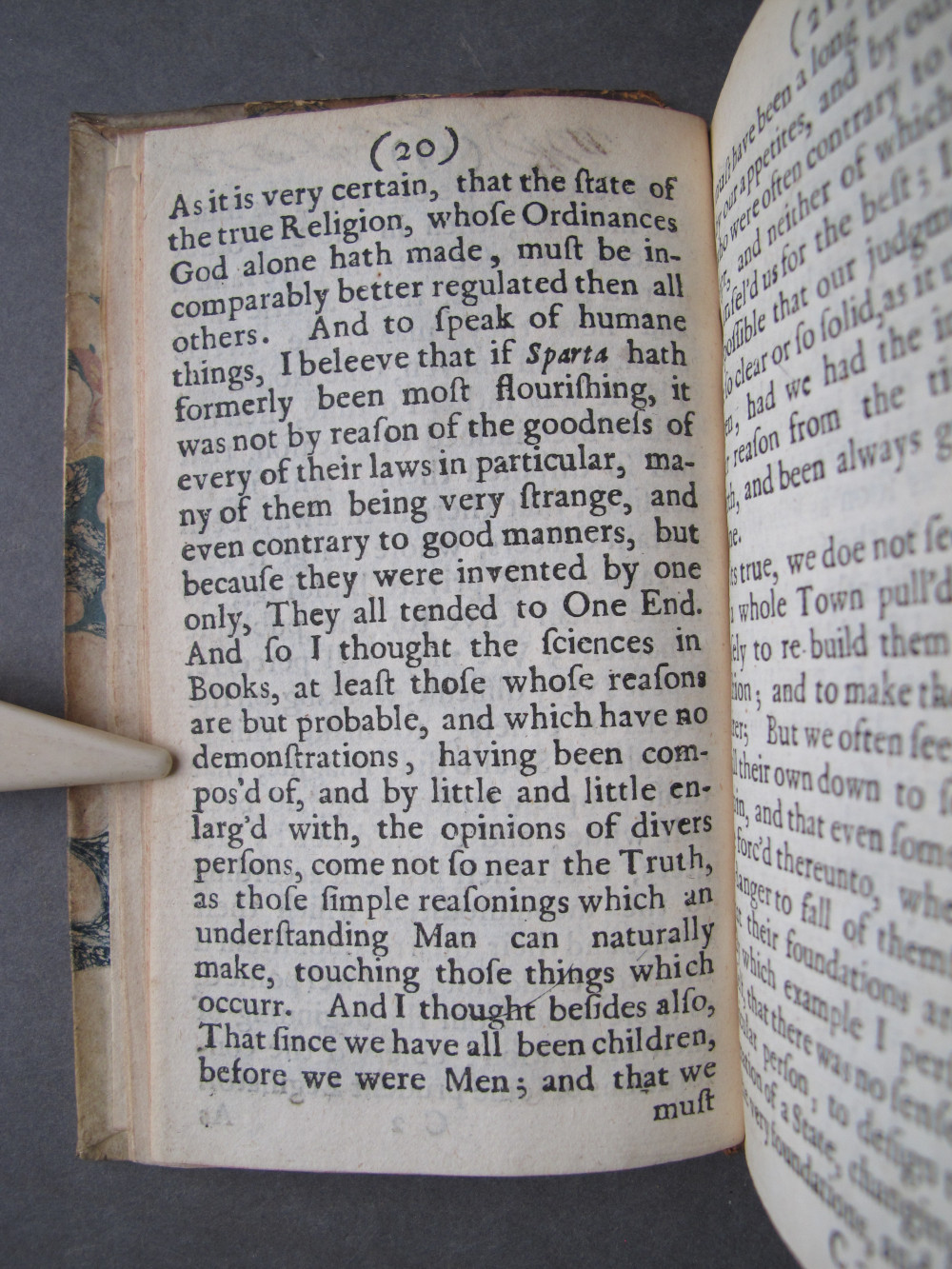

[Image 38 / 152]

(Page 20)

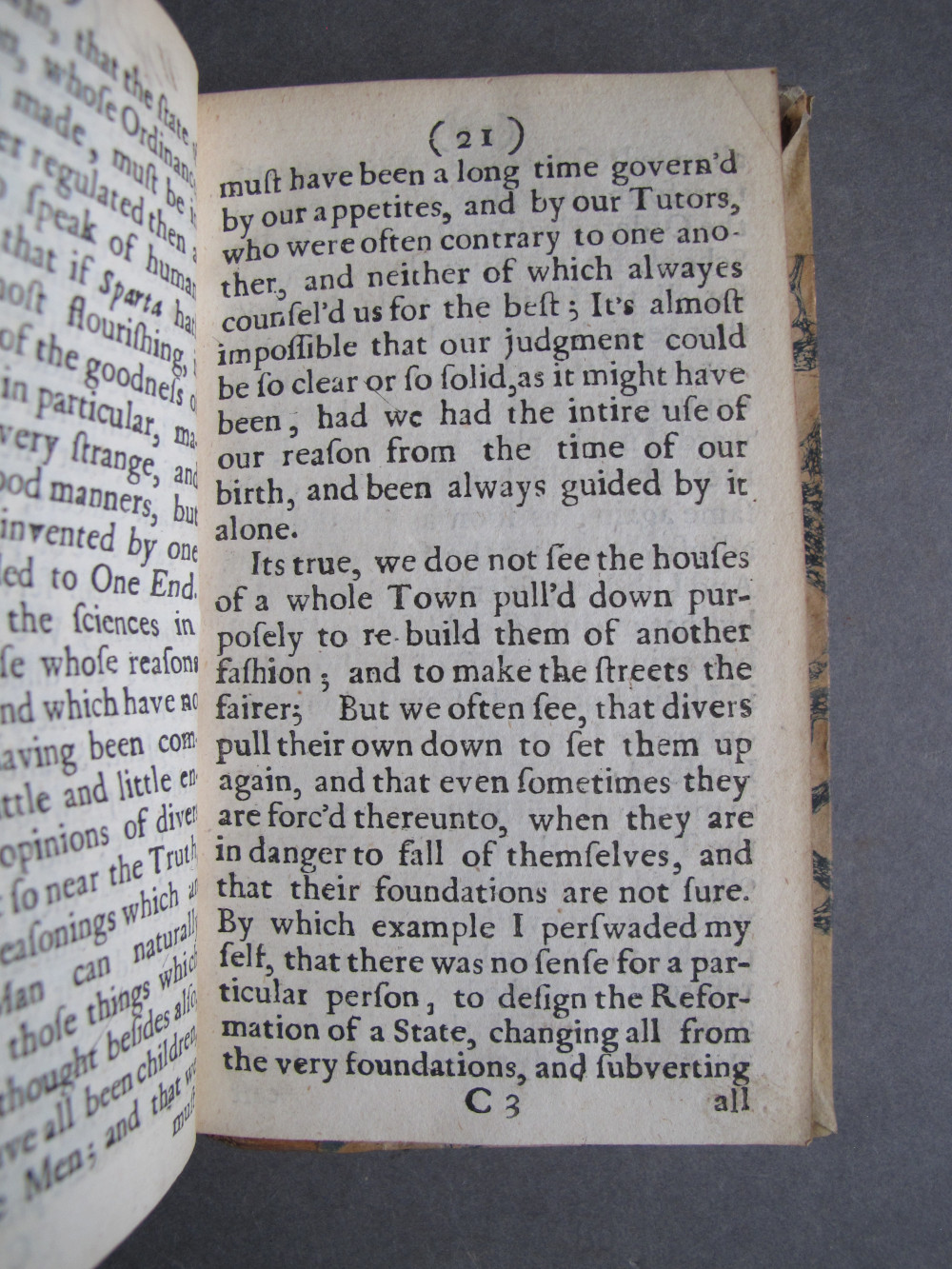

[Image 39 / 152]

(Page 21)

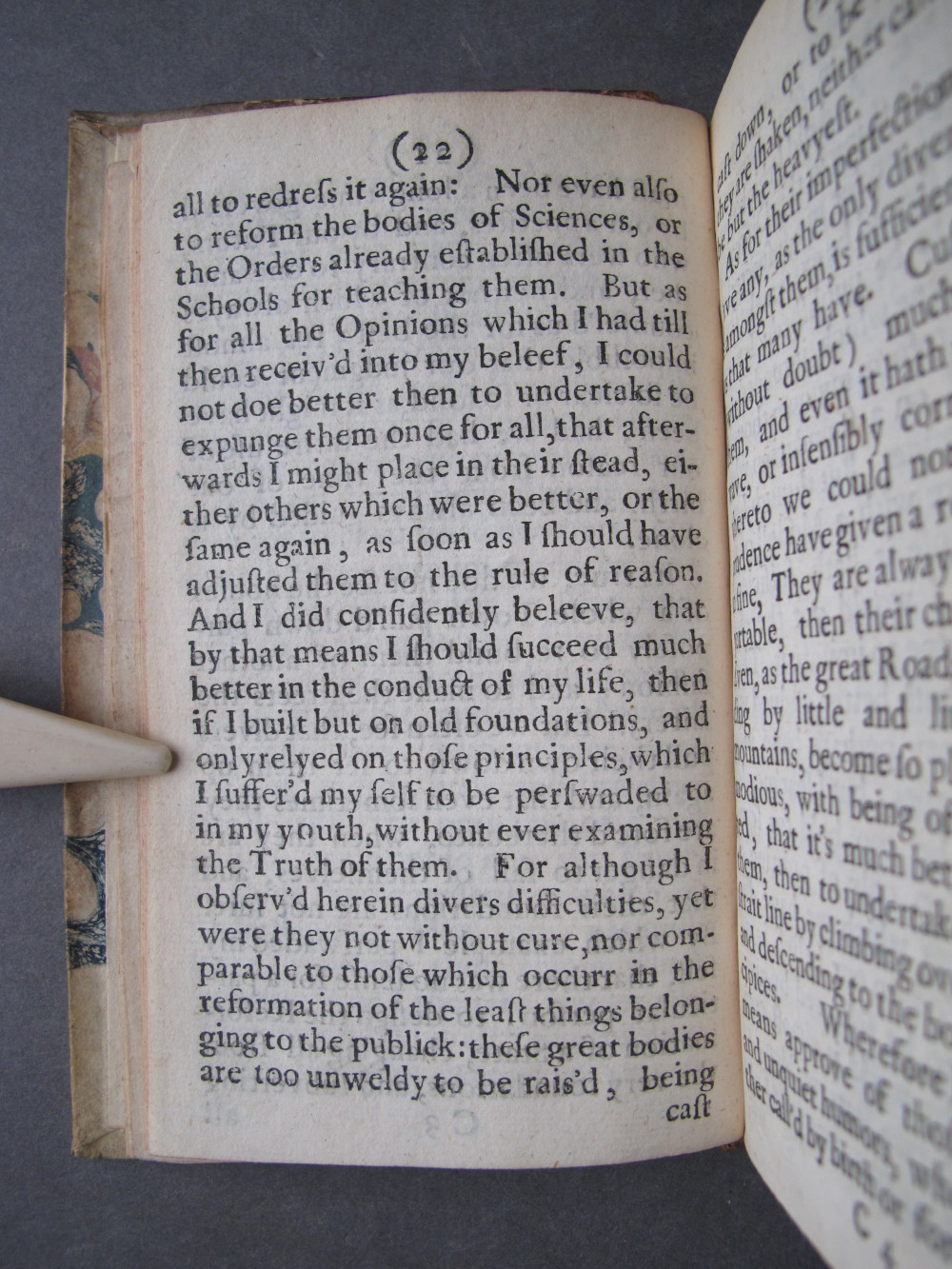

[Image 40 / 152]

(Page 22)

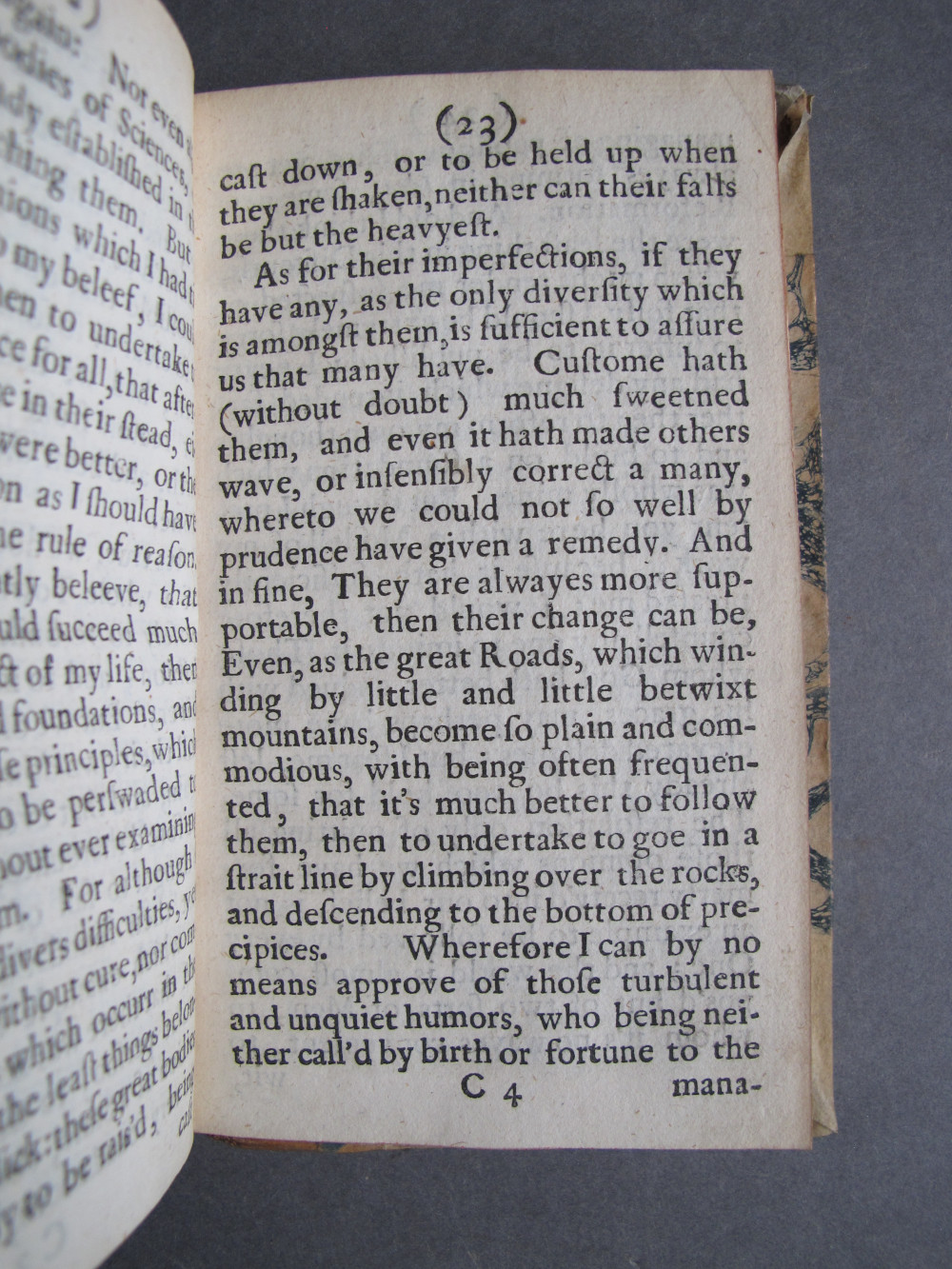

[Image 41 / 152]

(Page 23)

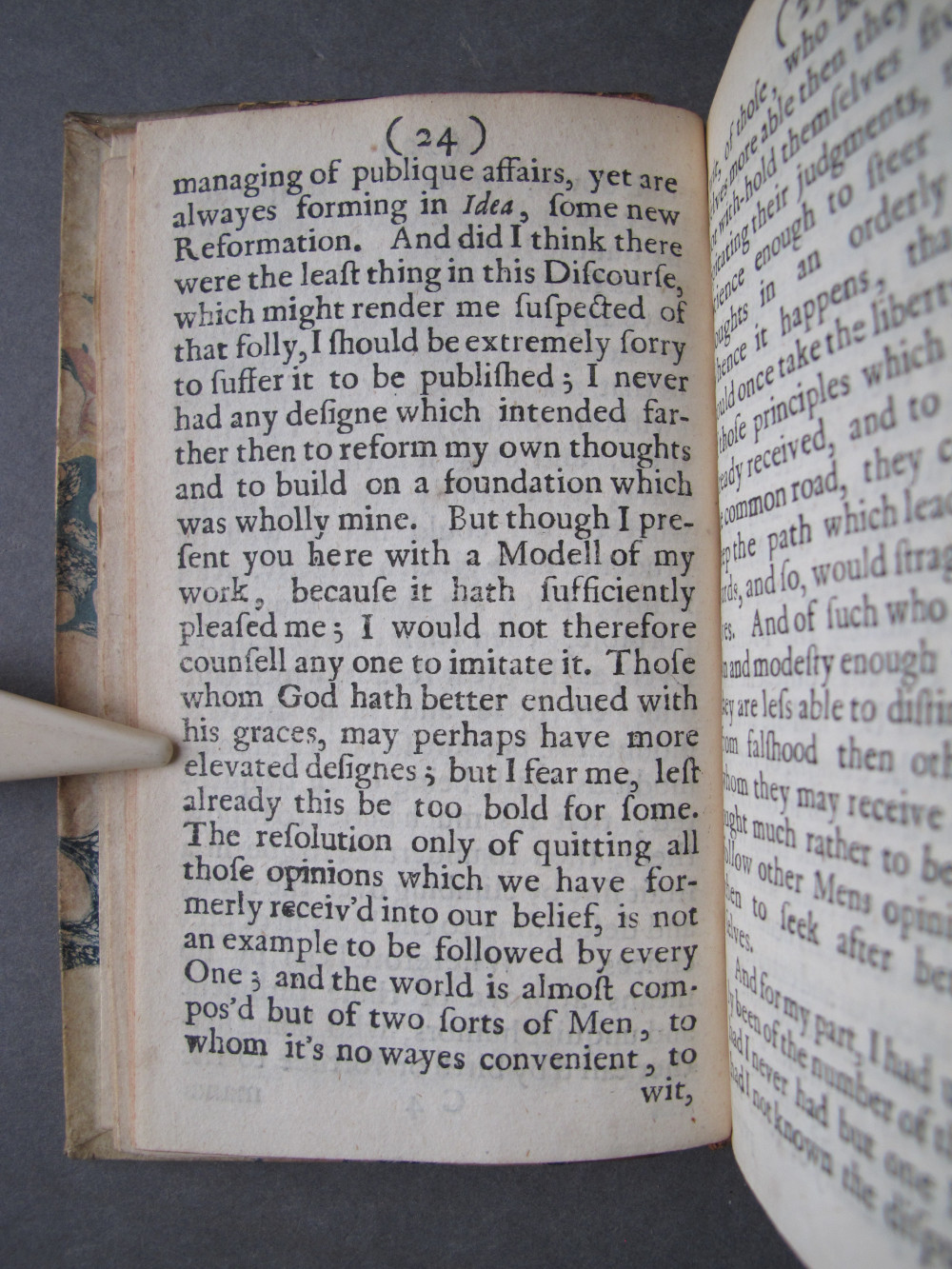

[Image 42 / 152]

(Page 24)

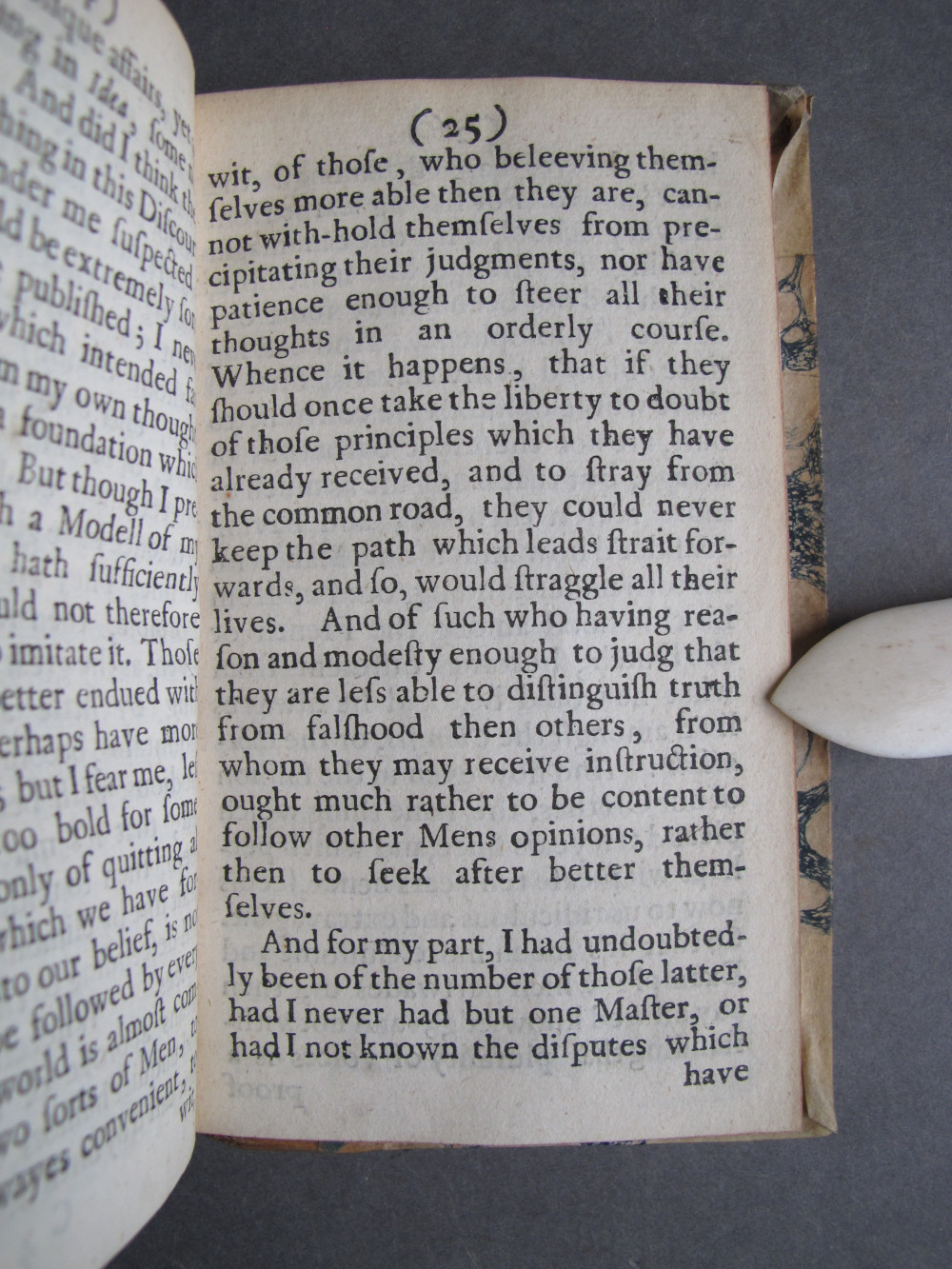

[Image 43 / 152]

(Page 25)

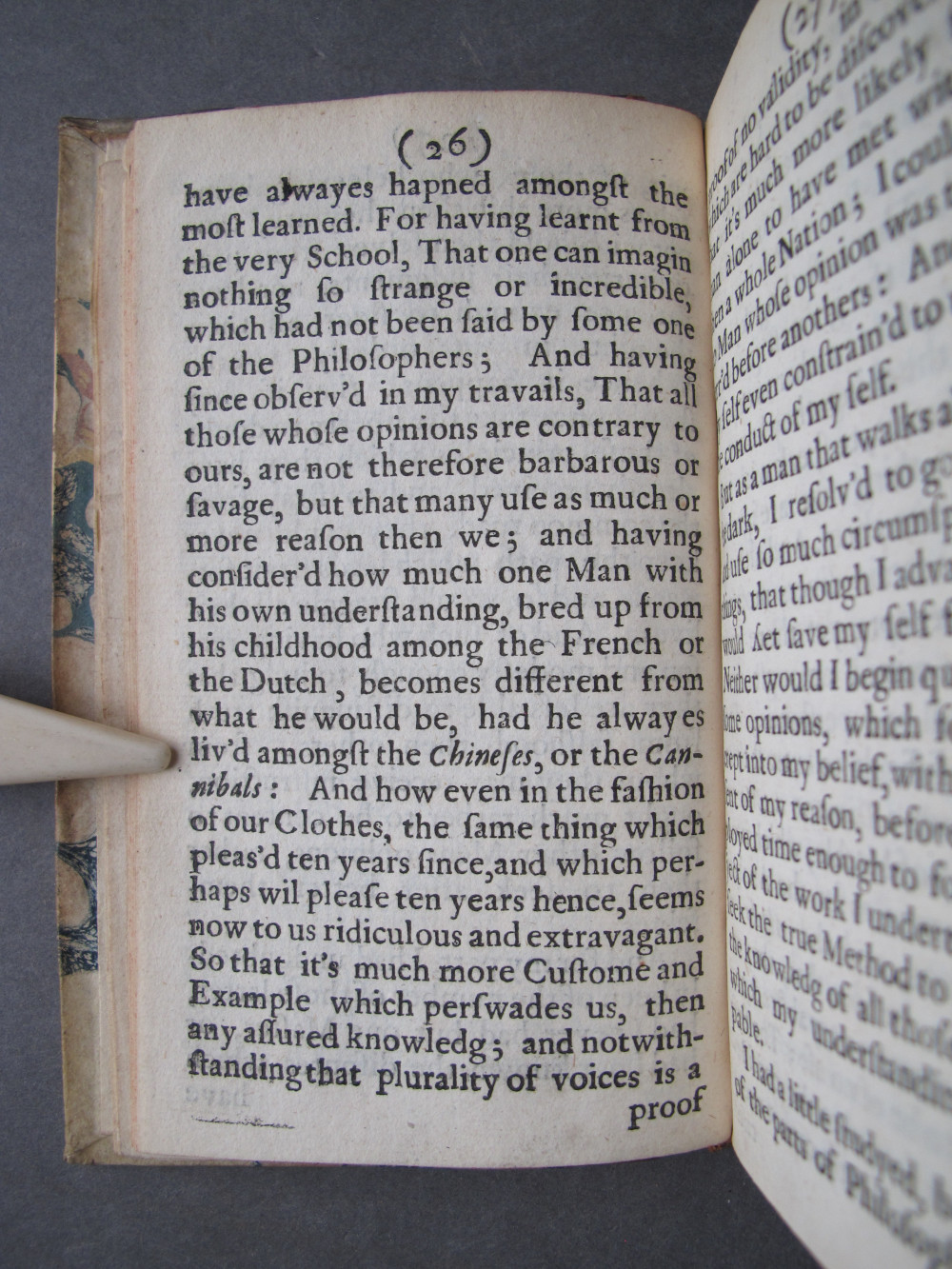

[Image 44 / 152]

(Page 26)

[Image 45 / 152]

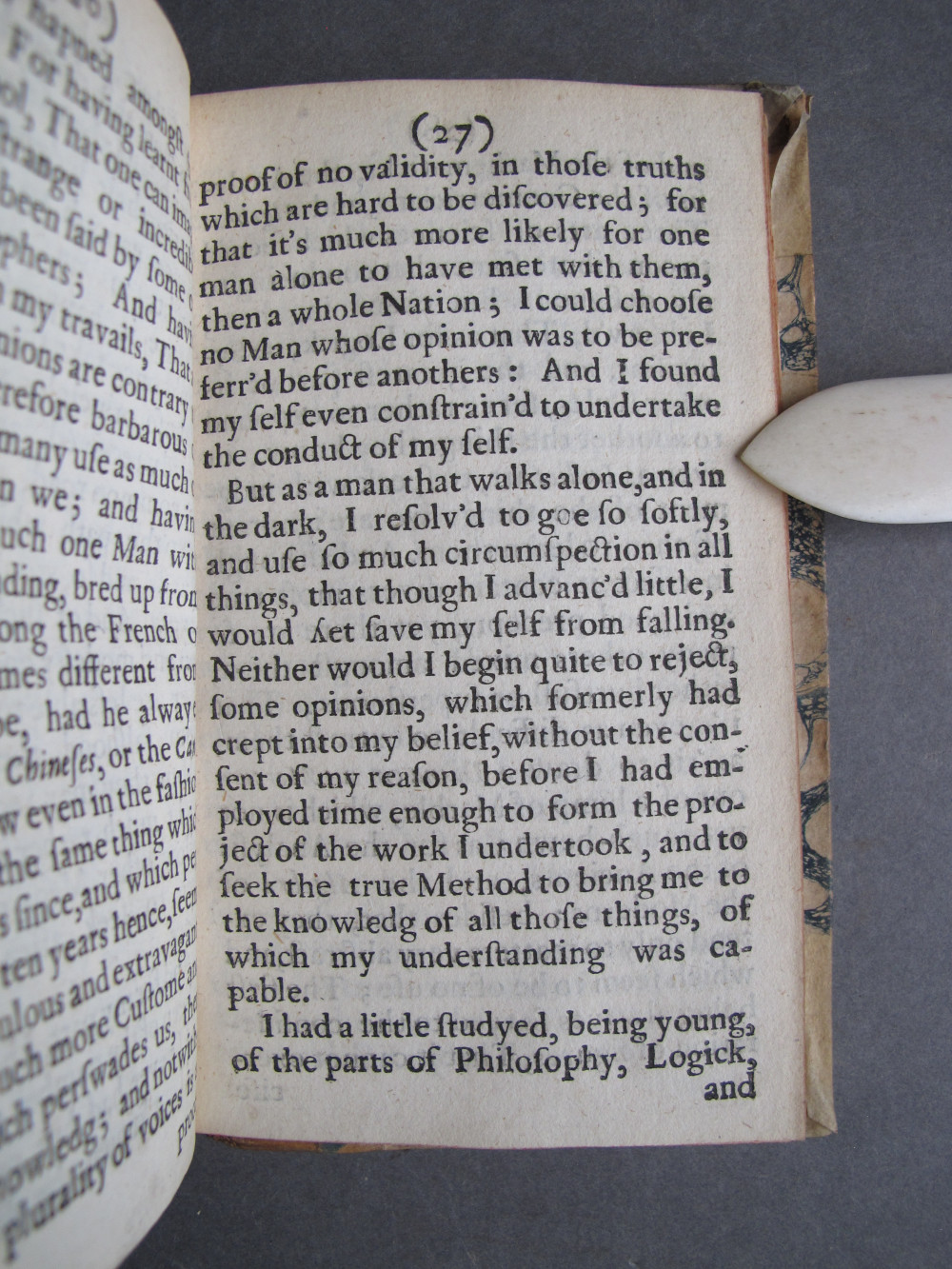

(Page 27)

[Image 46 / 152]

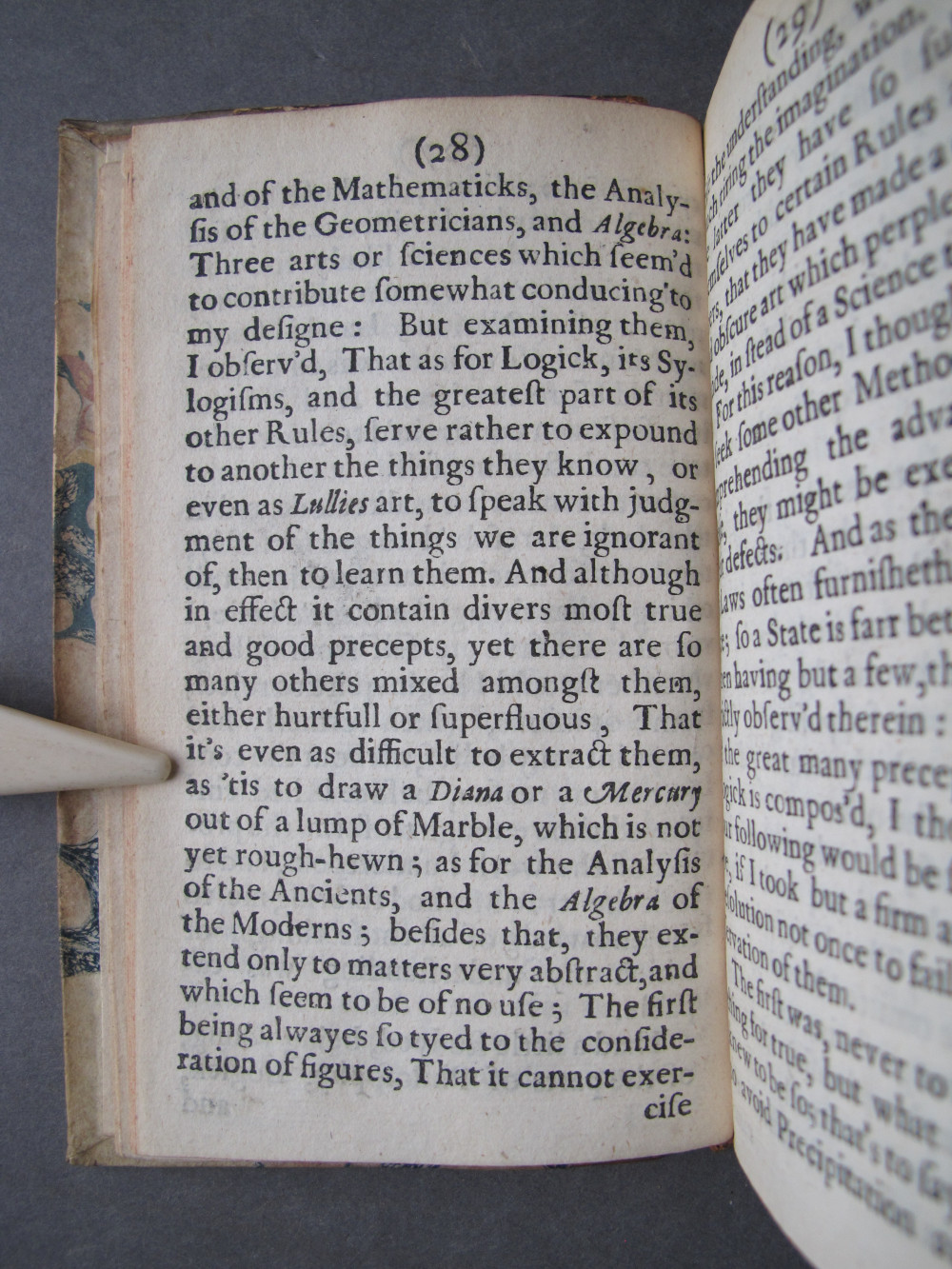

(Page 28)

[Image 47 / 152]

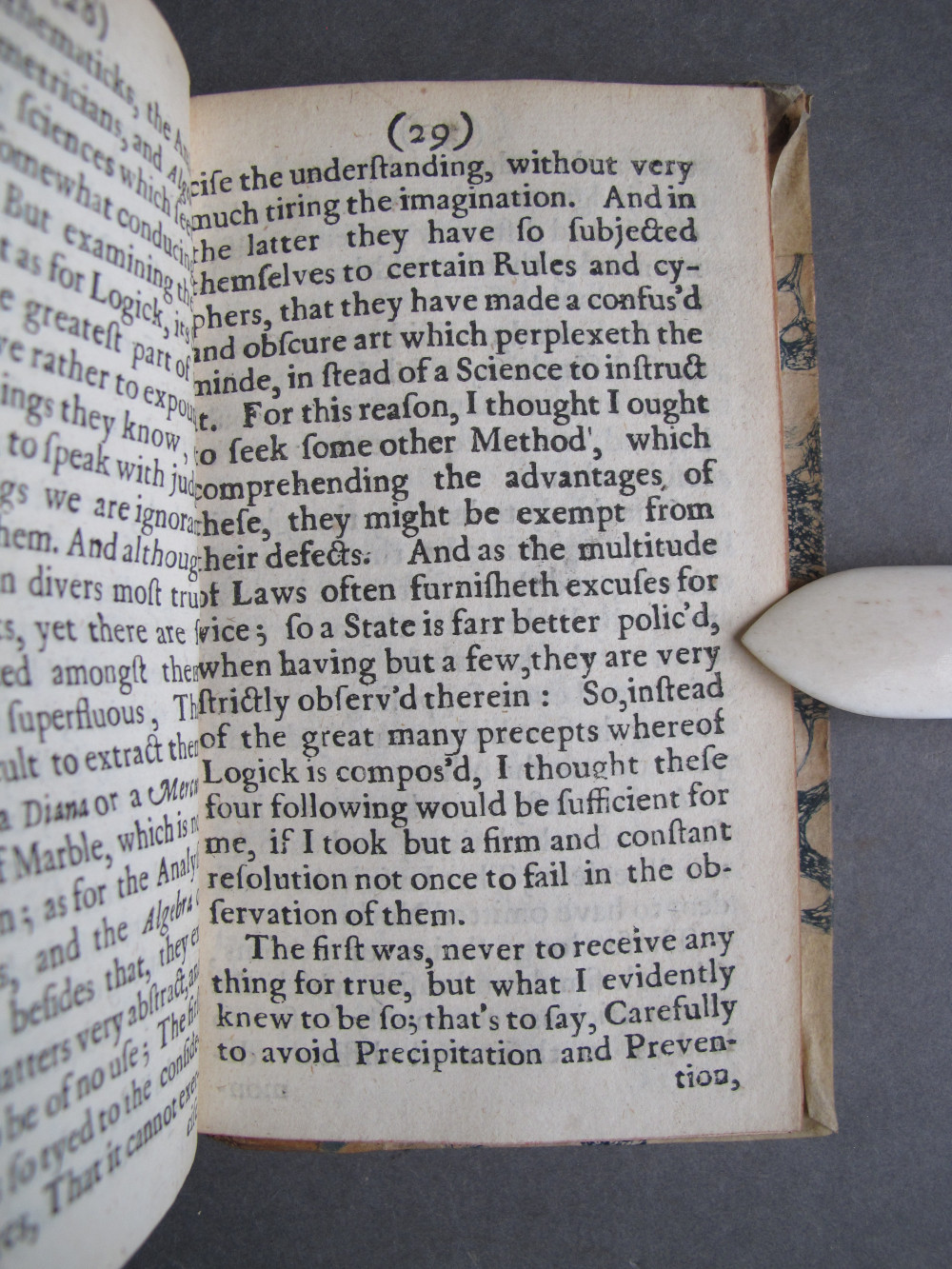

(Page 29)

[Image 48 / 152]

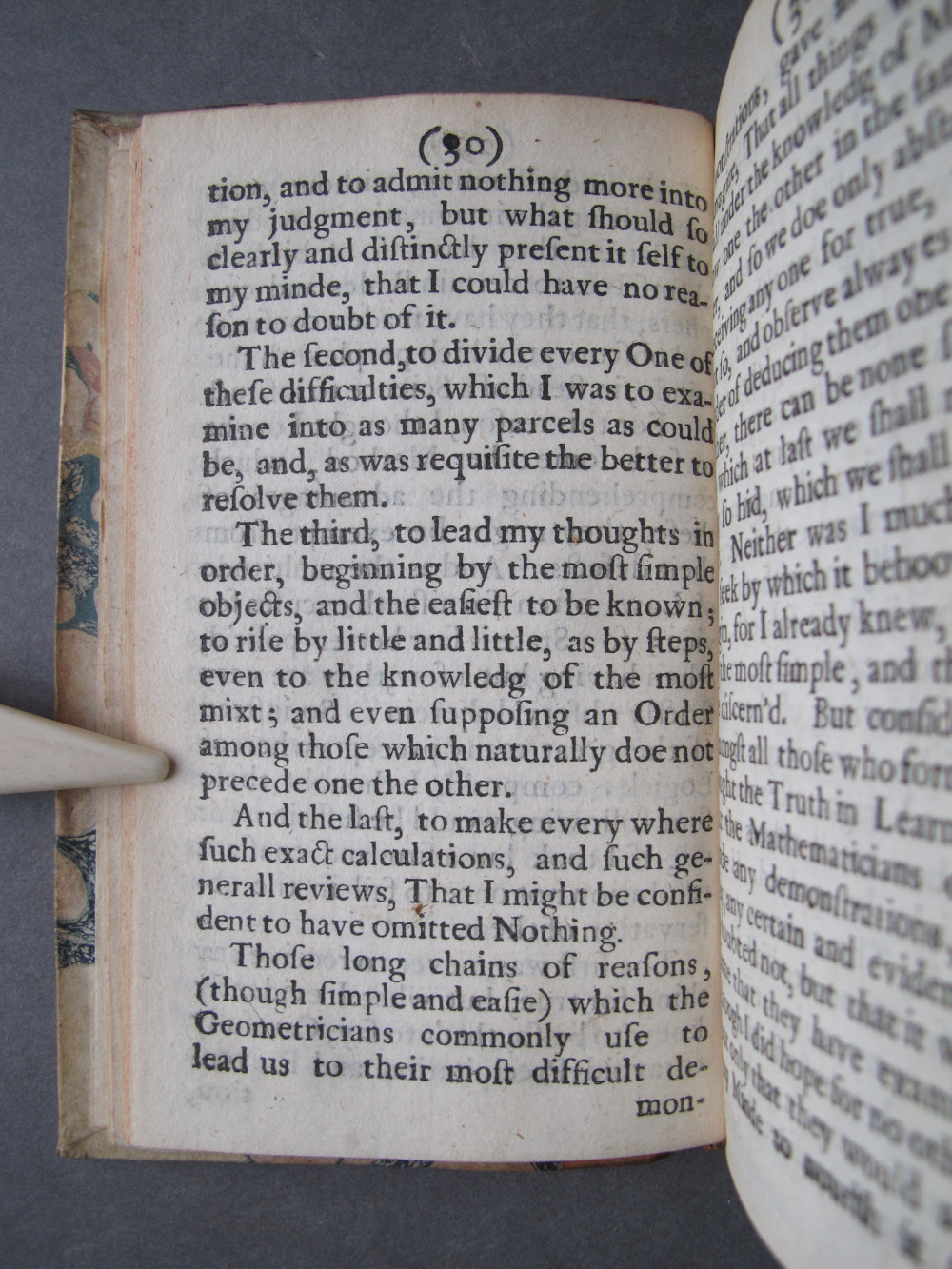

(Page 30)

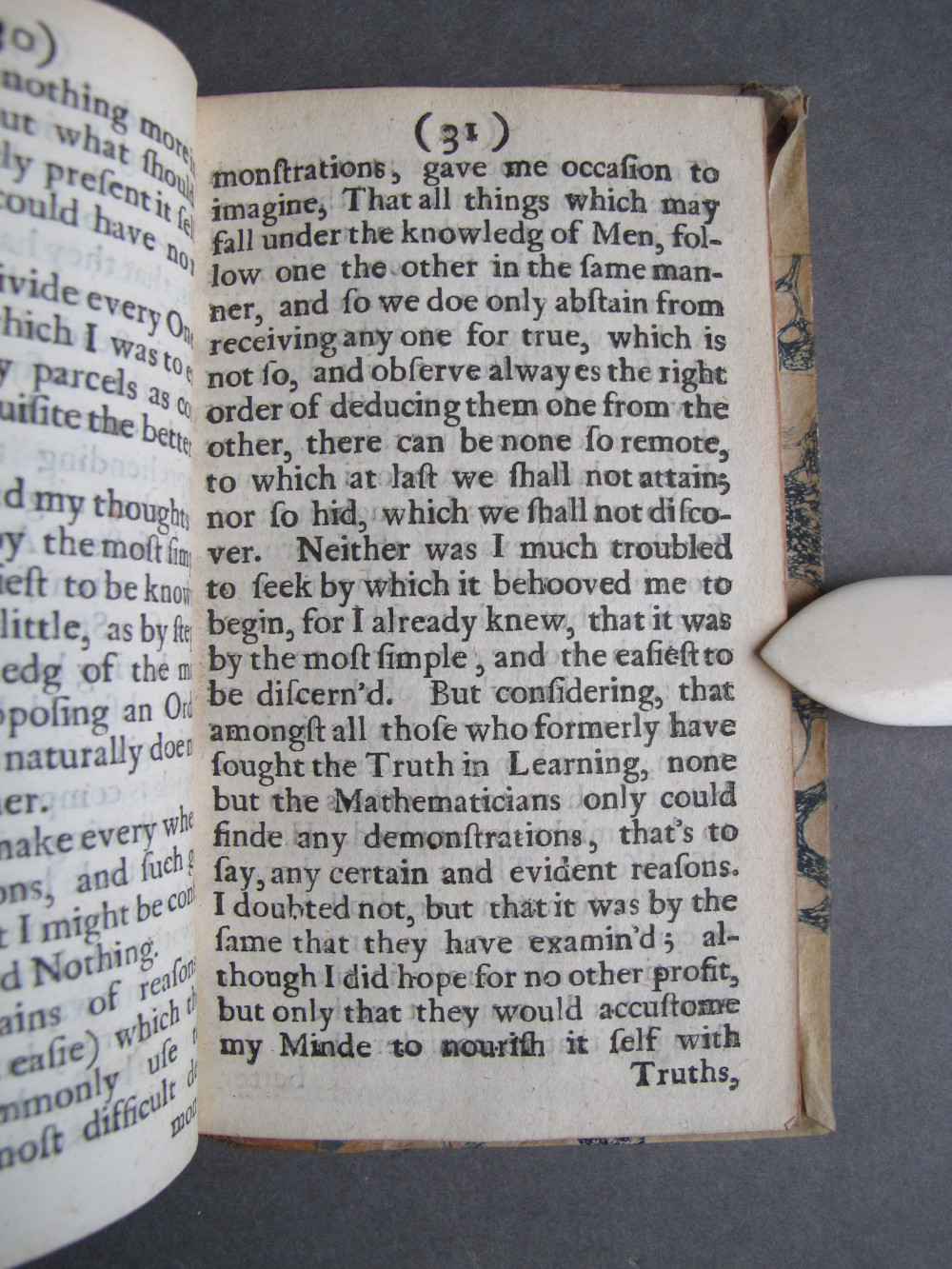

[Image 49 / 152]

(Page 31)

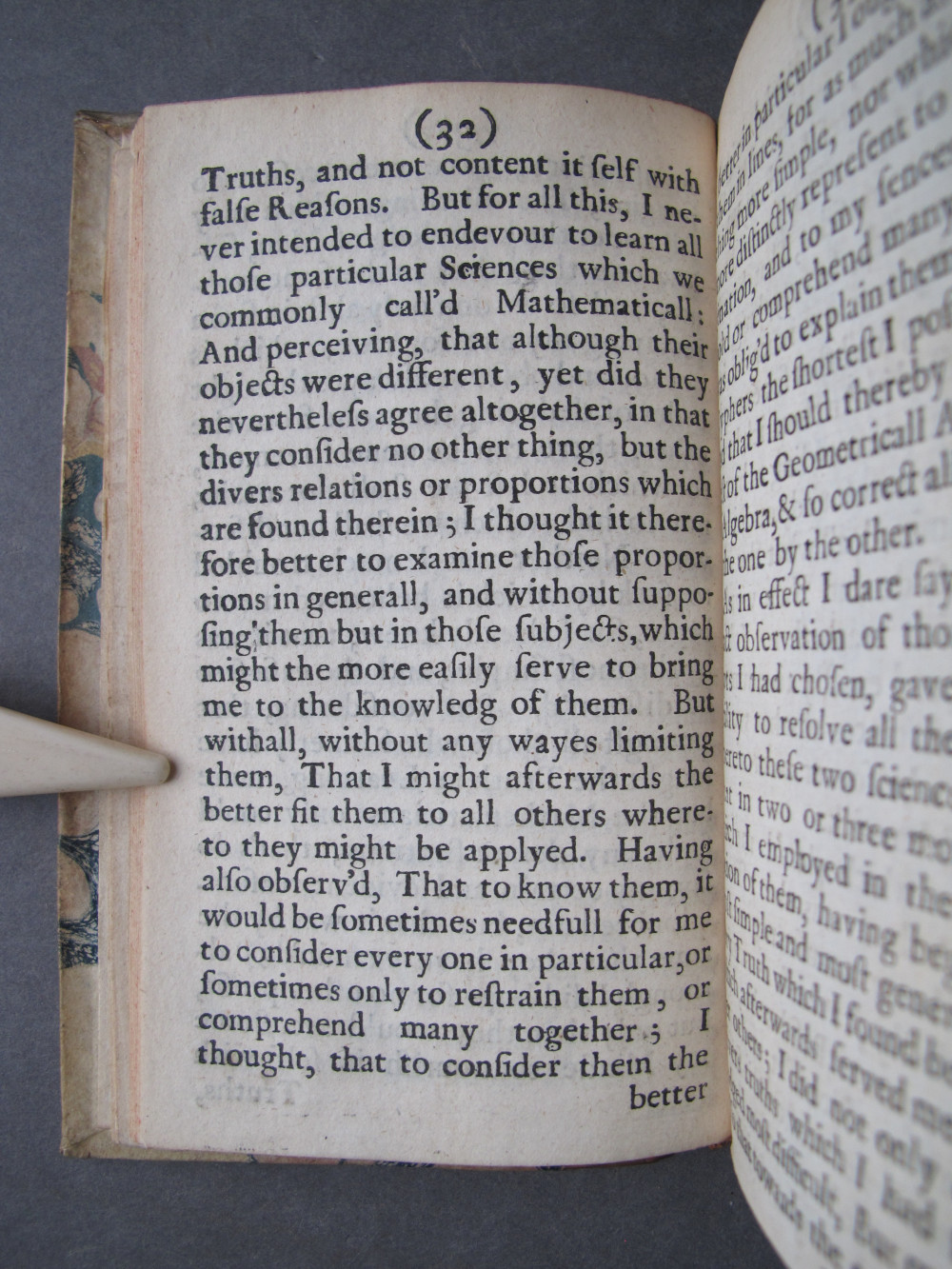

[Image 50 / 152]

(Page 32)

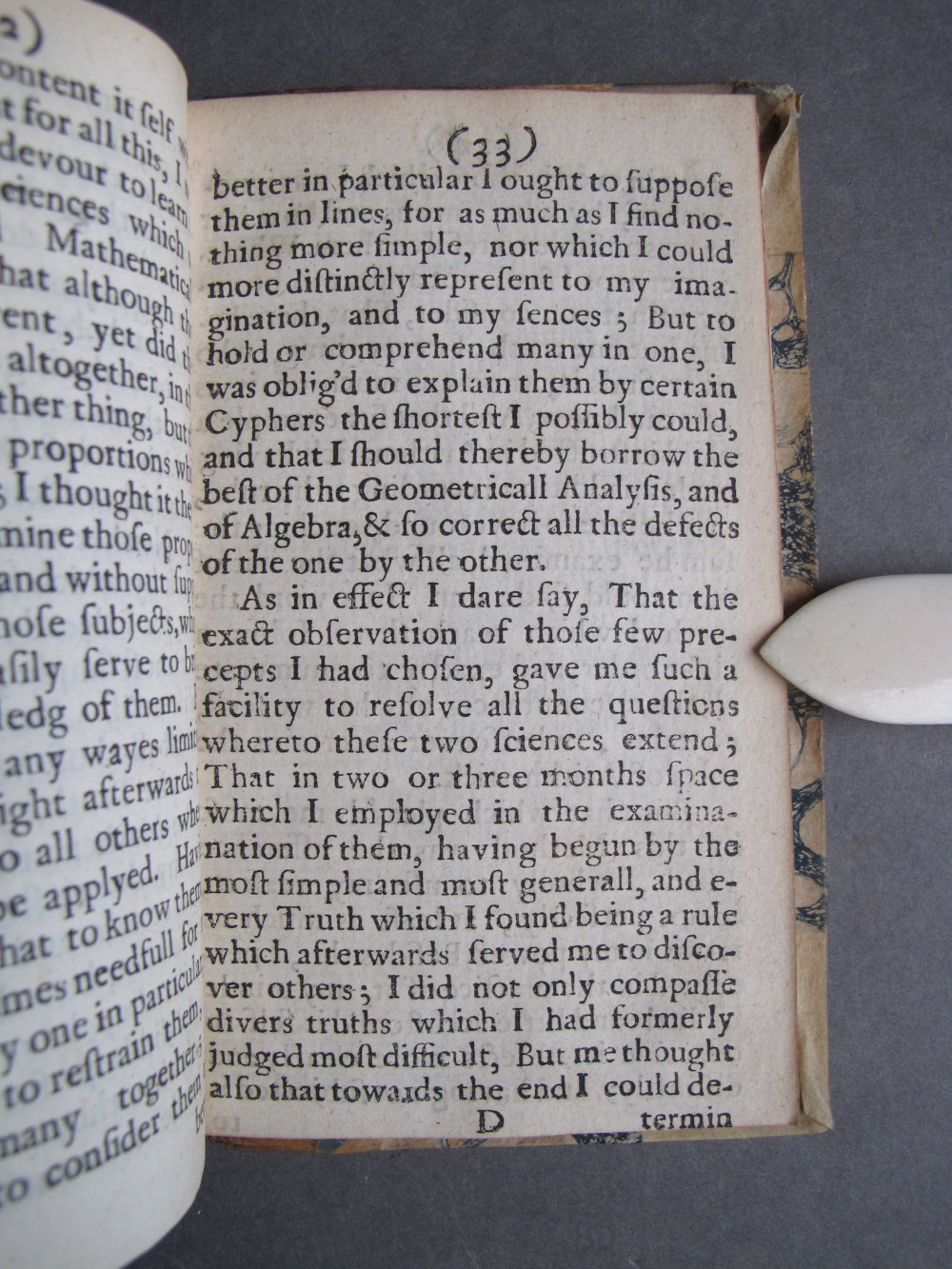

[Image 51 / 152]

(Page 33)

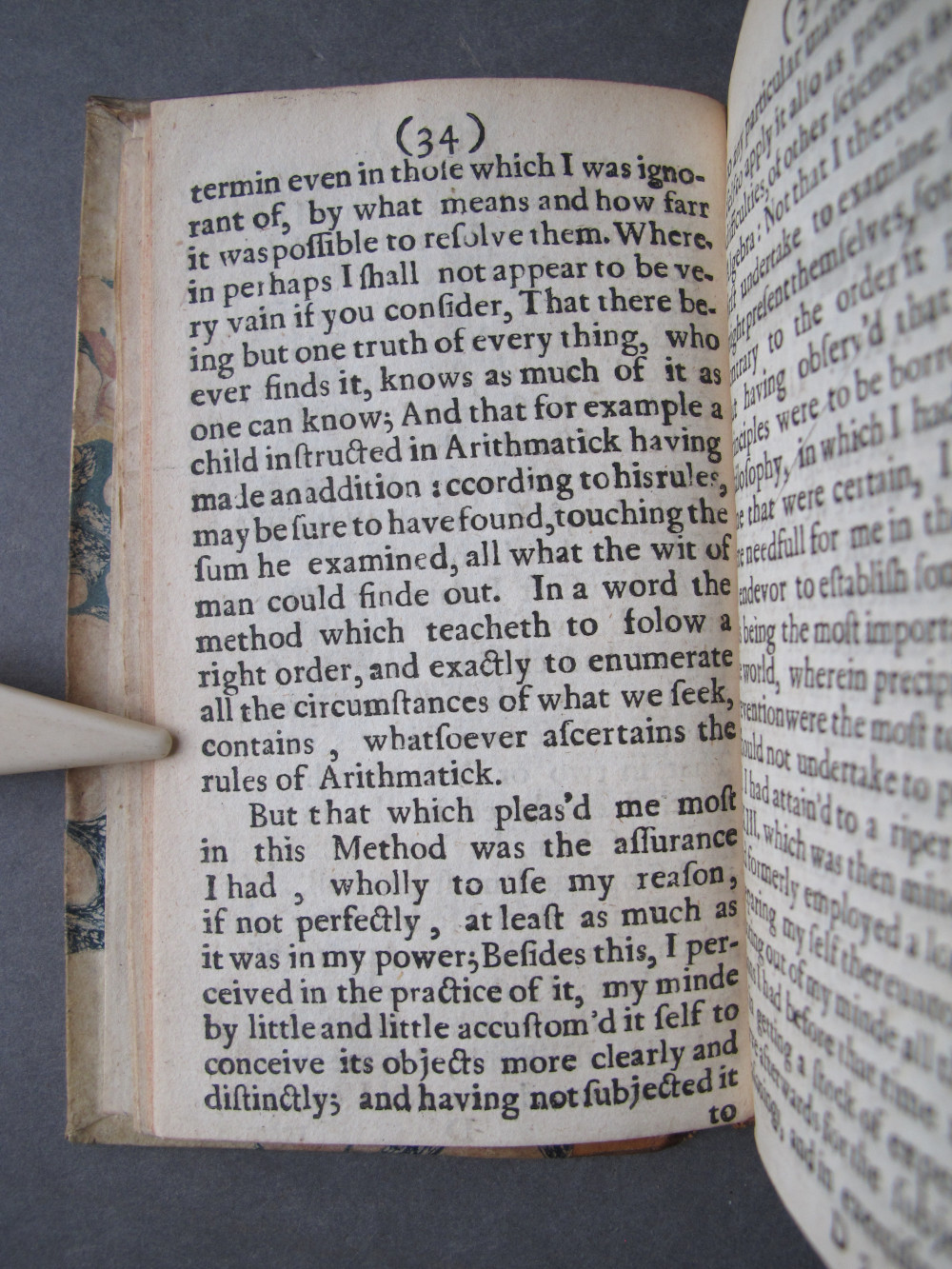

[Image 52 / 152]

(Page 34)

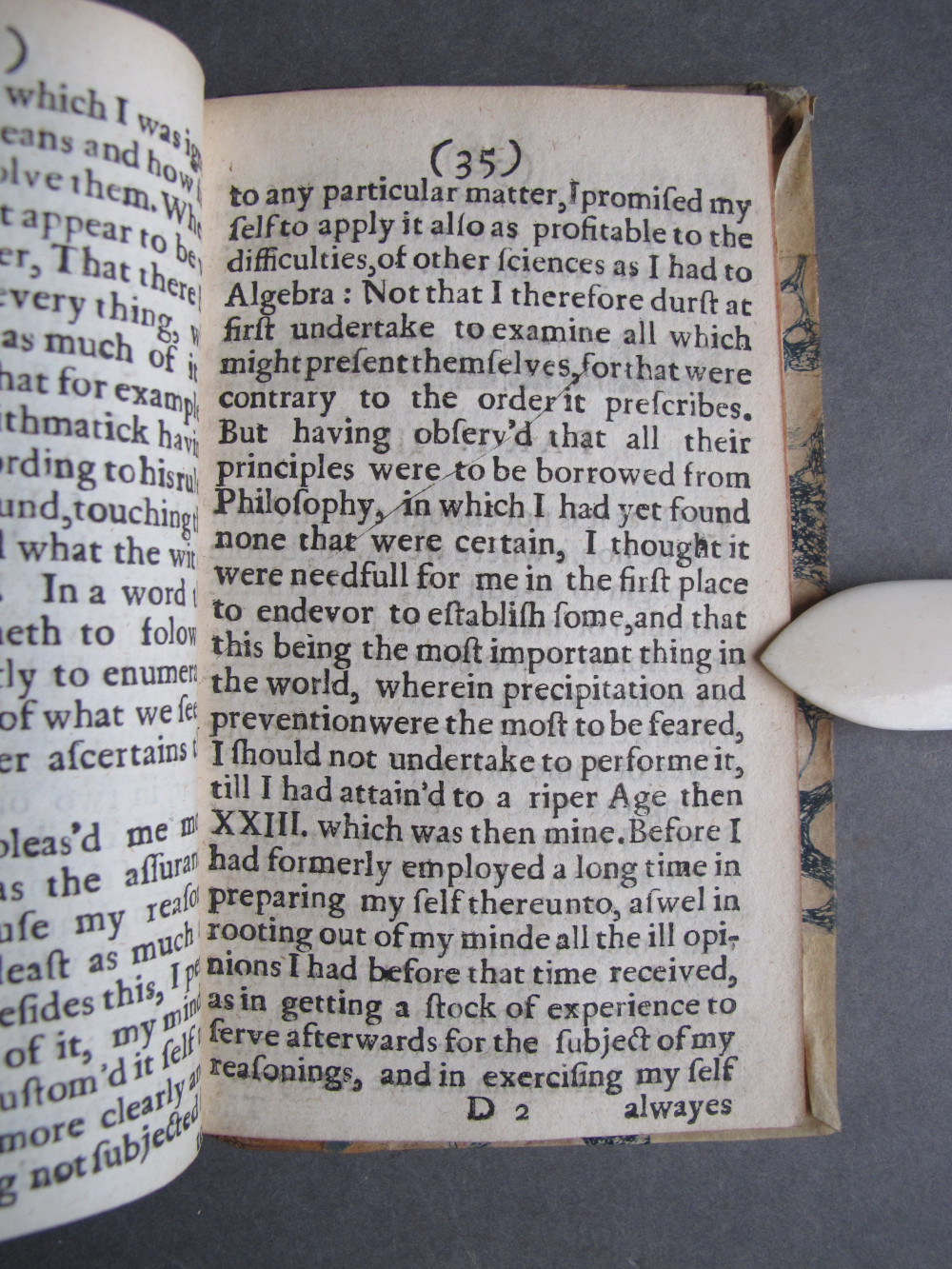

[Image 53 / 152]

(Page 35)

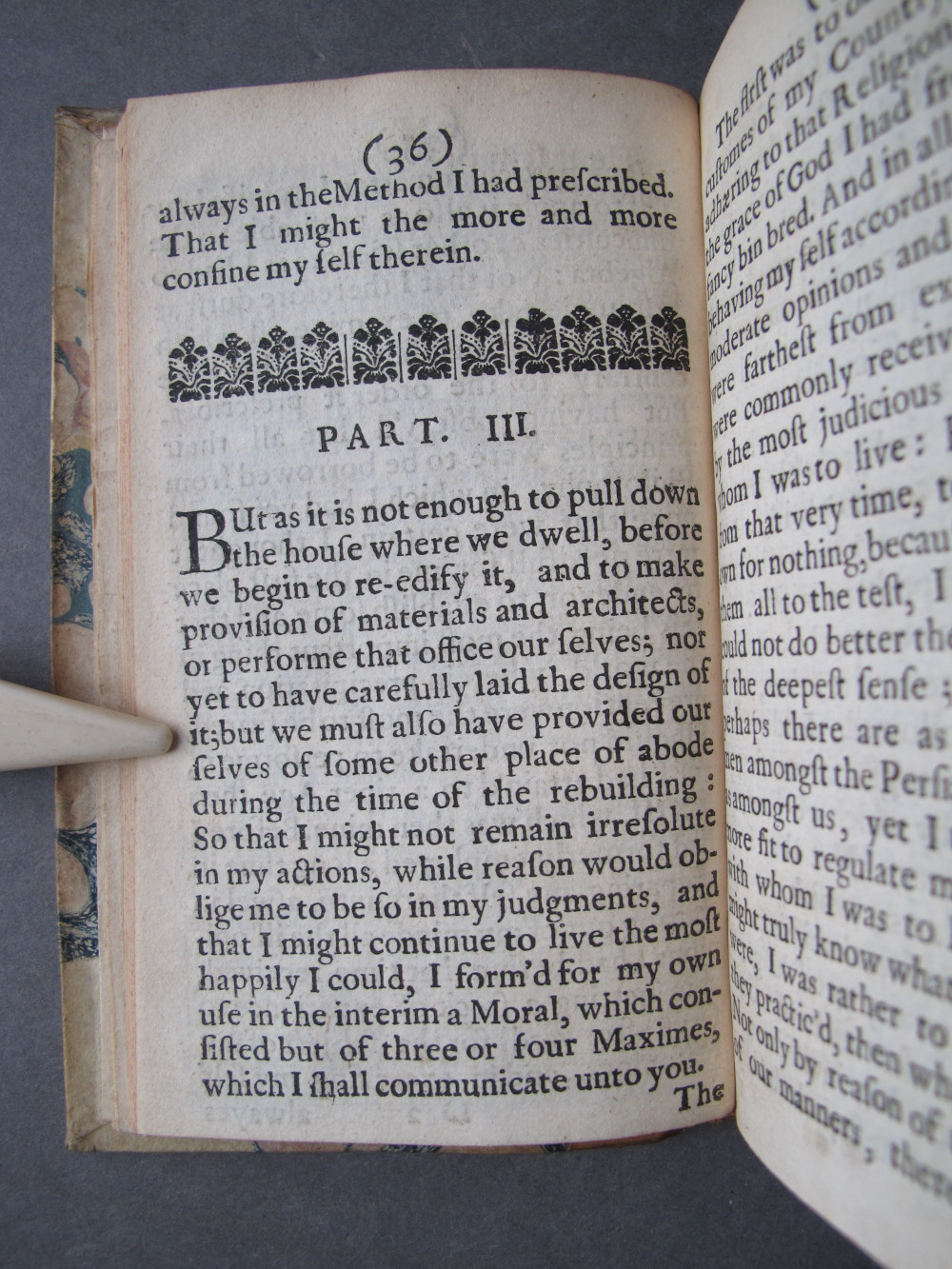

[Image 54 / 152]

(Page 36)

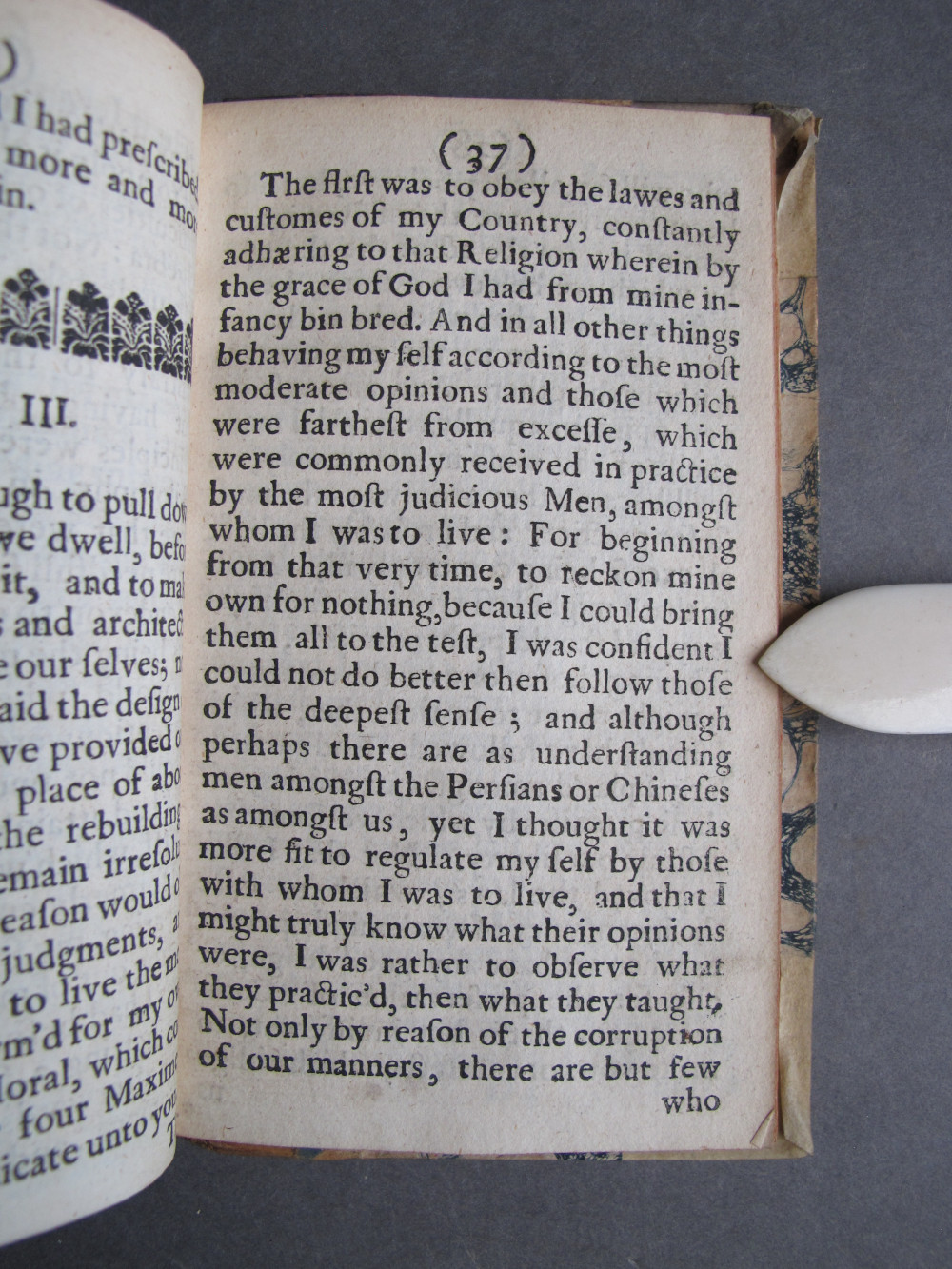

[Image 55 / 152]

(Page 37)

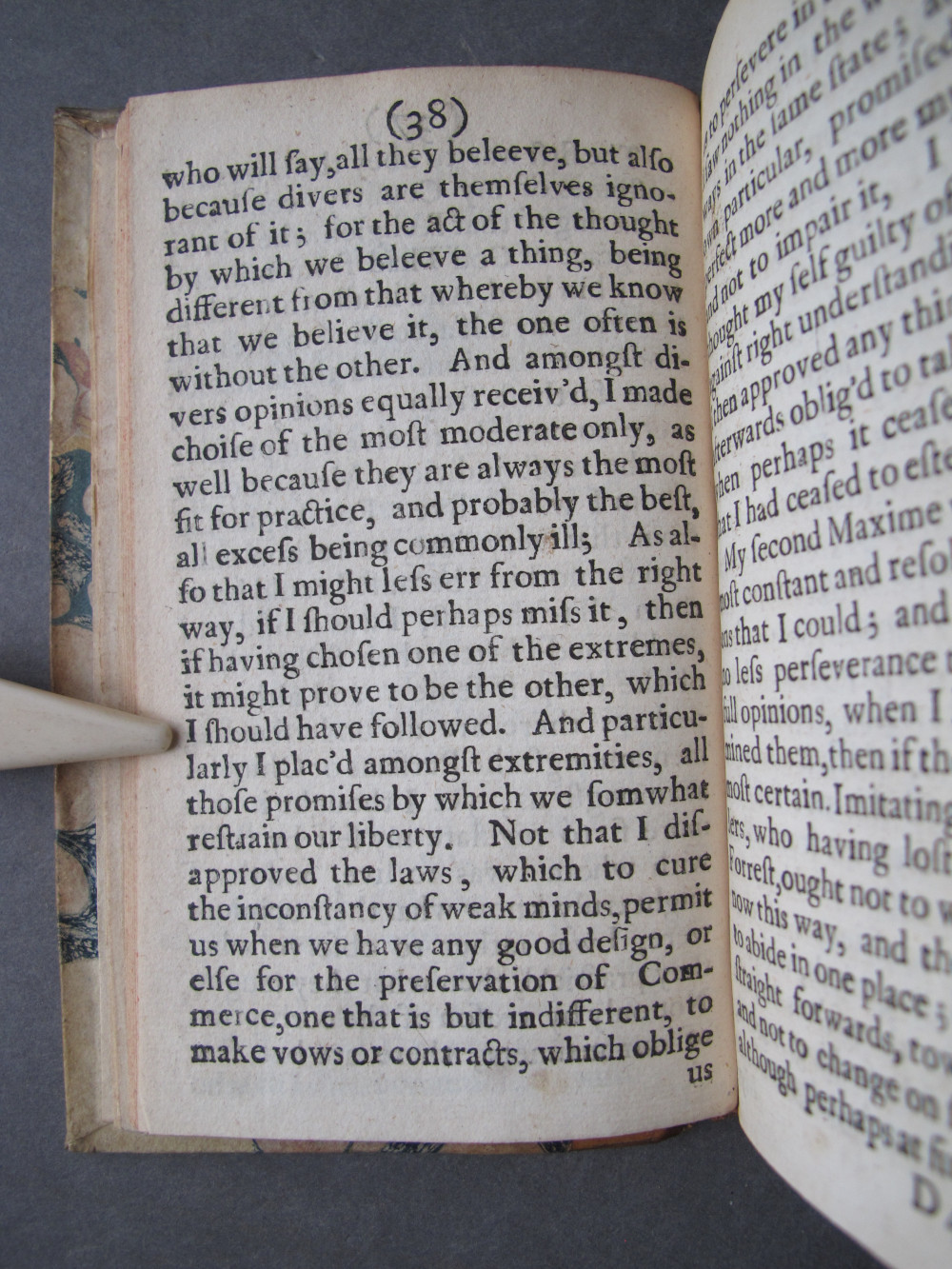

[Image 56 / 152]

(Page 38)

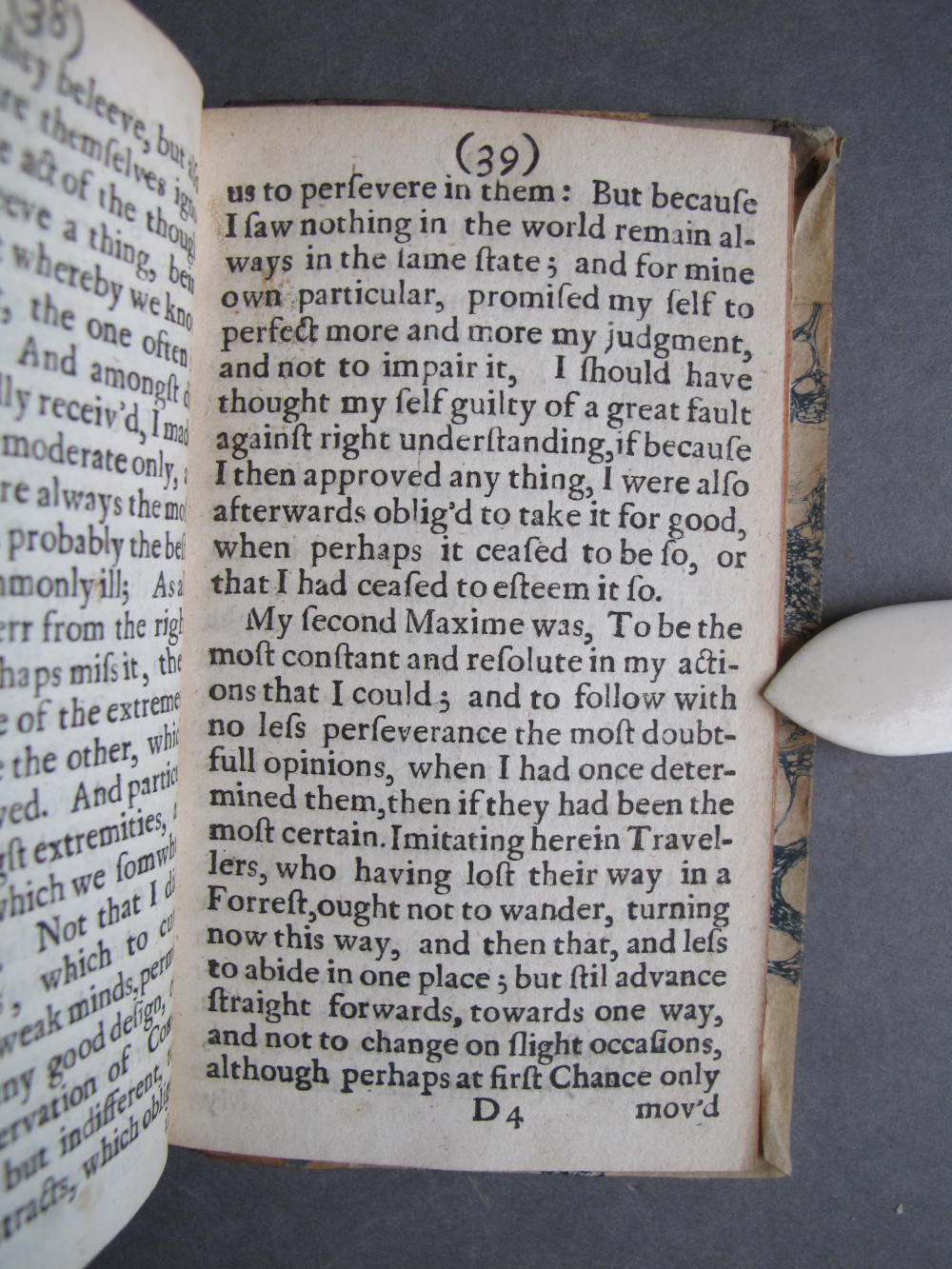

[Image 57 / 152]

(Page 39)

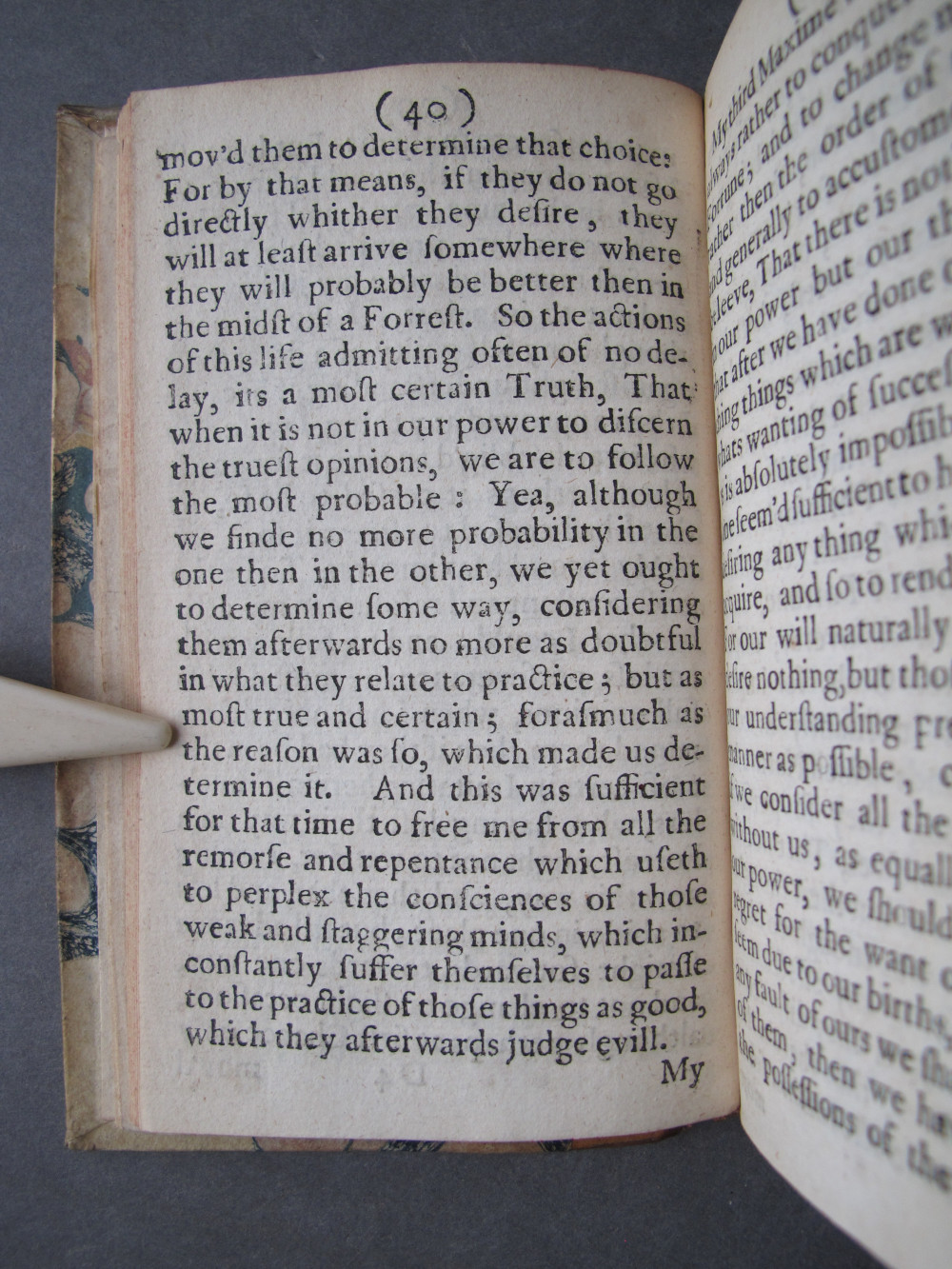

[Image 58 / 152]

(Page 40)

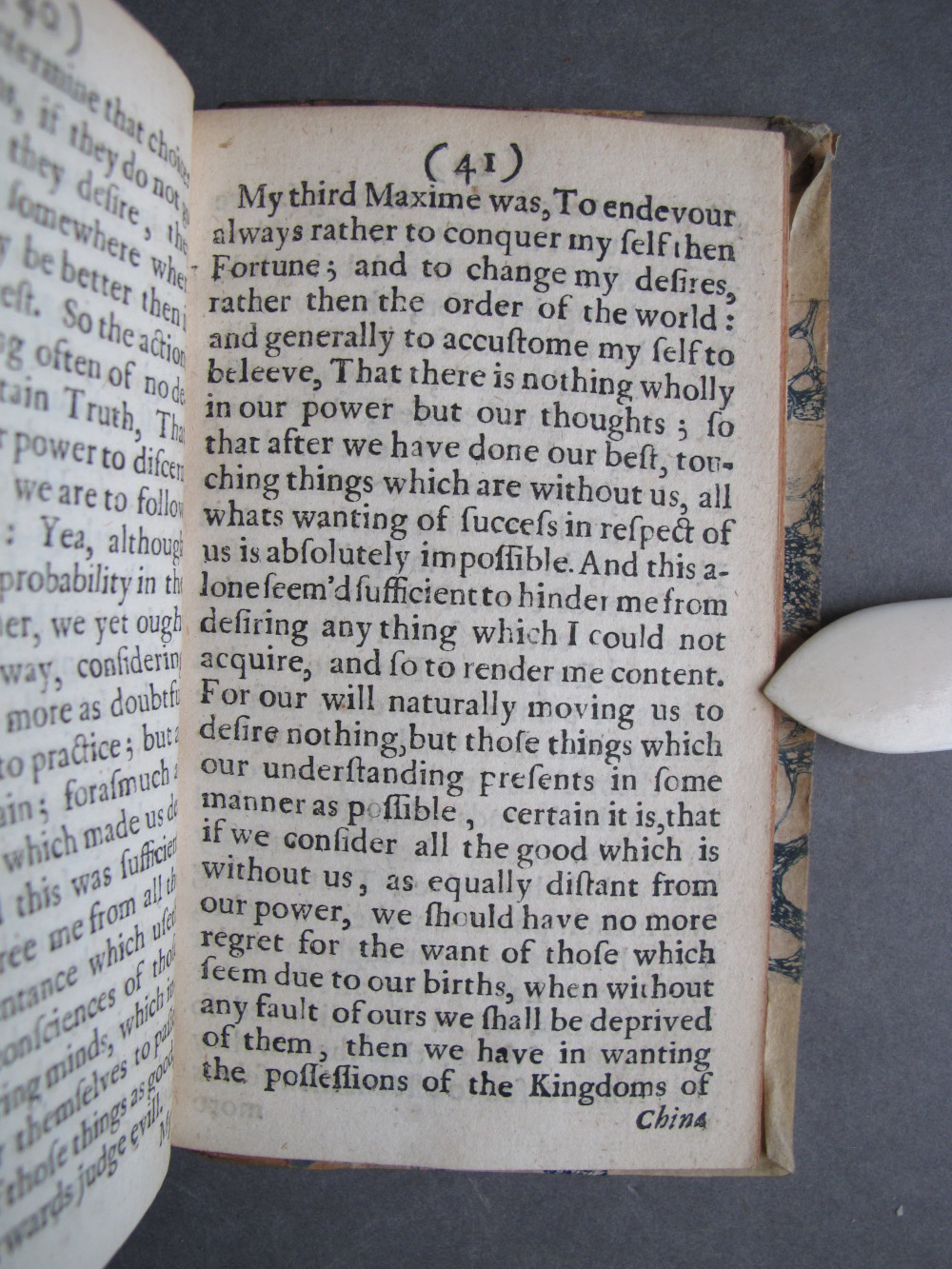

[Image 59 / 152]

(Page 41)

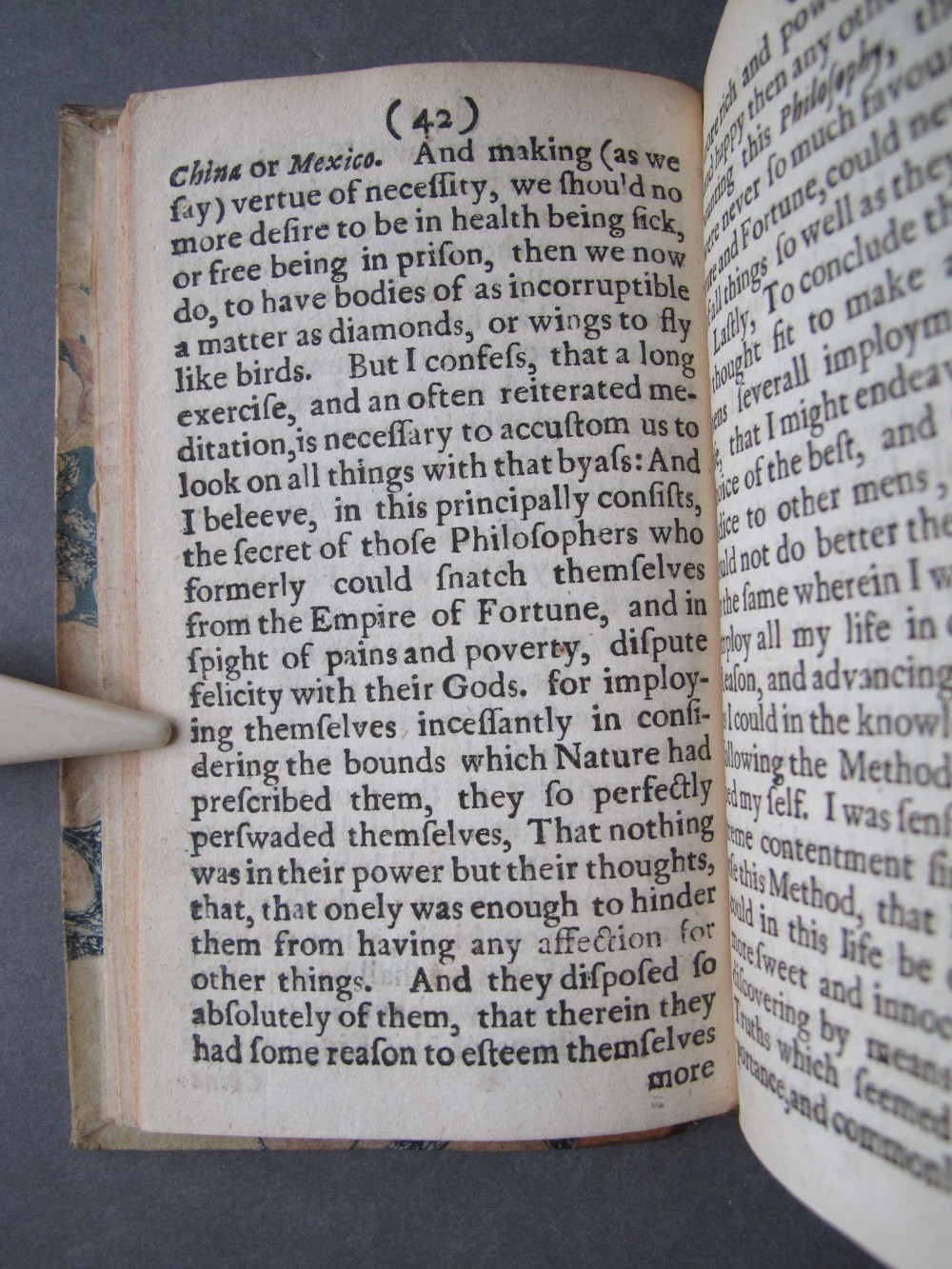

[Image 60 / 152]

(Page 42)

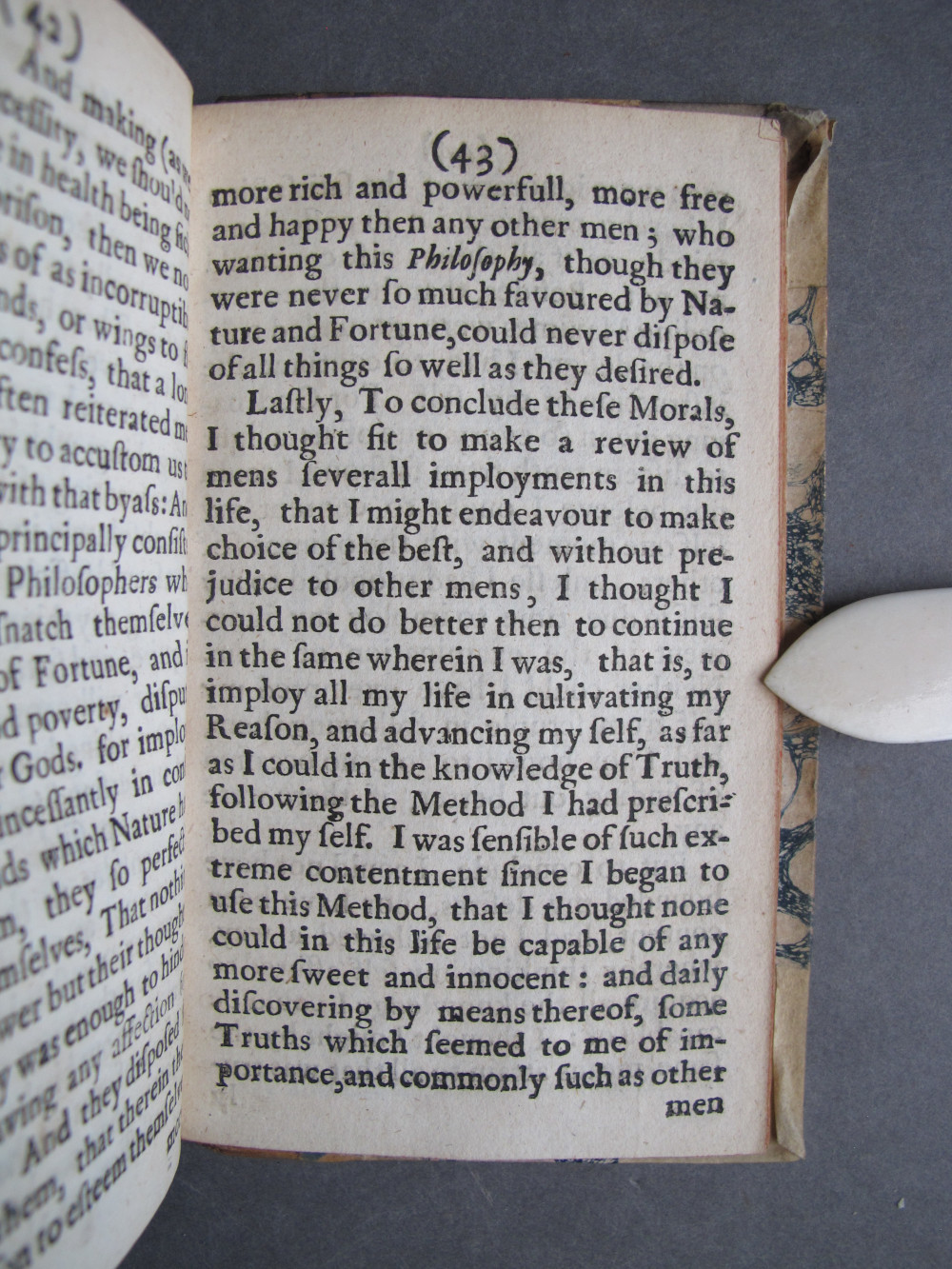

[Image 61 / 152]

(Page 43)

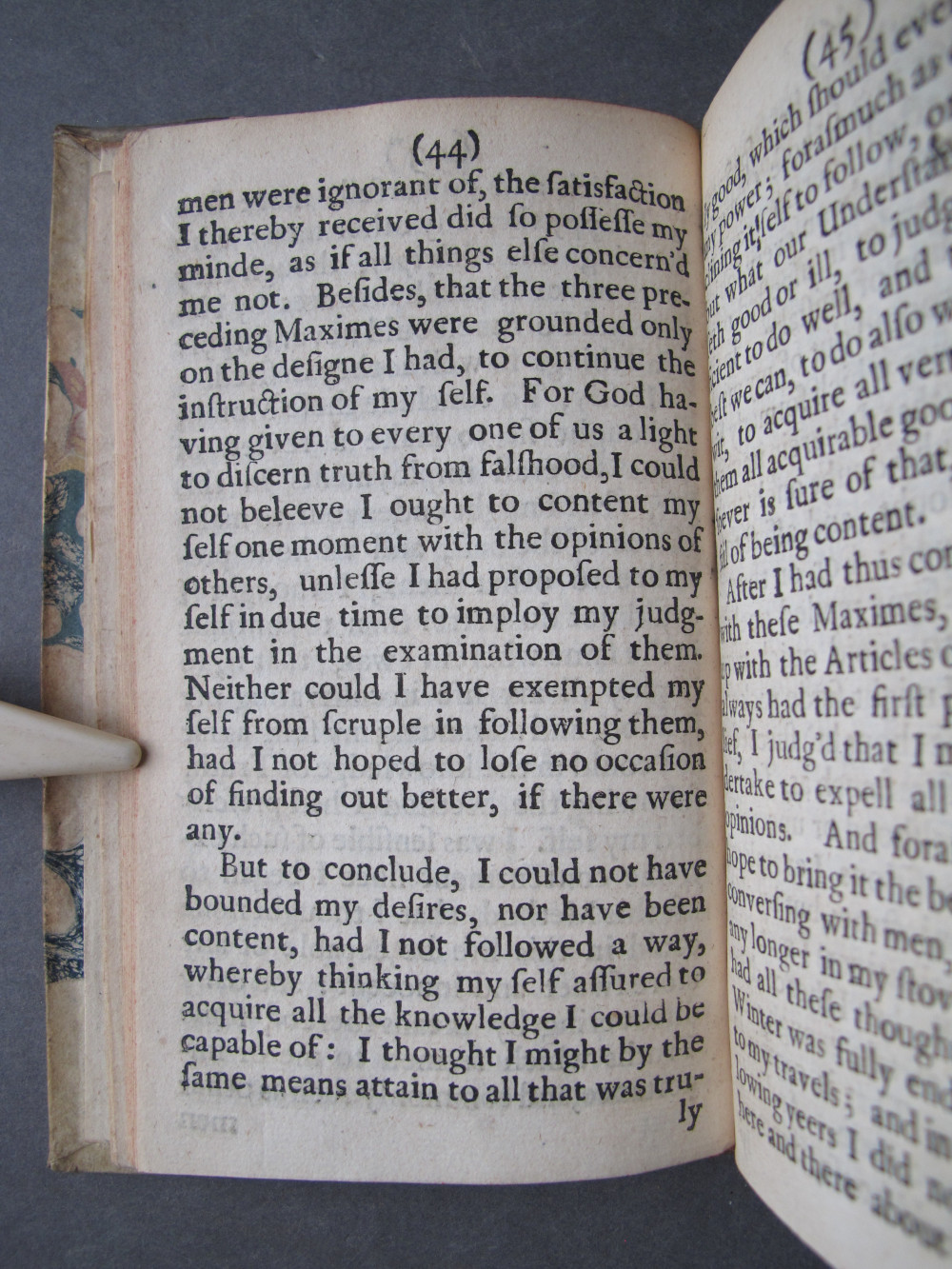

[Image 62 / 152]

(Page 44)

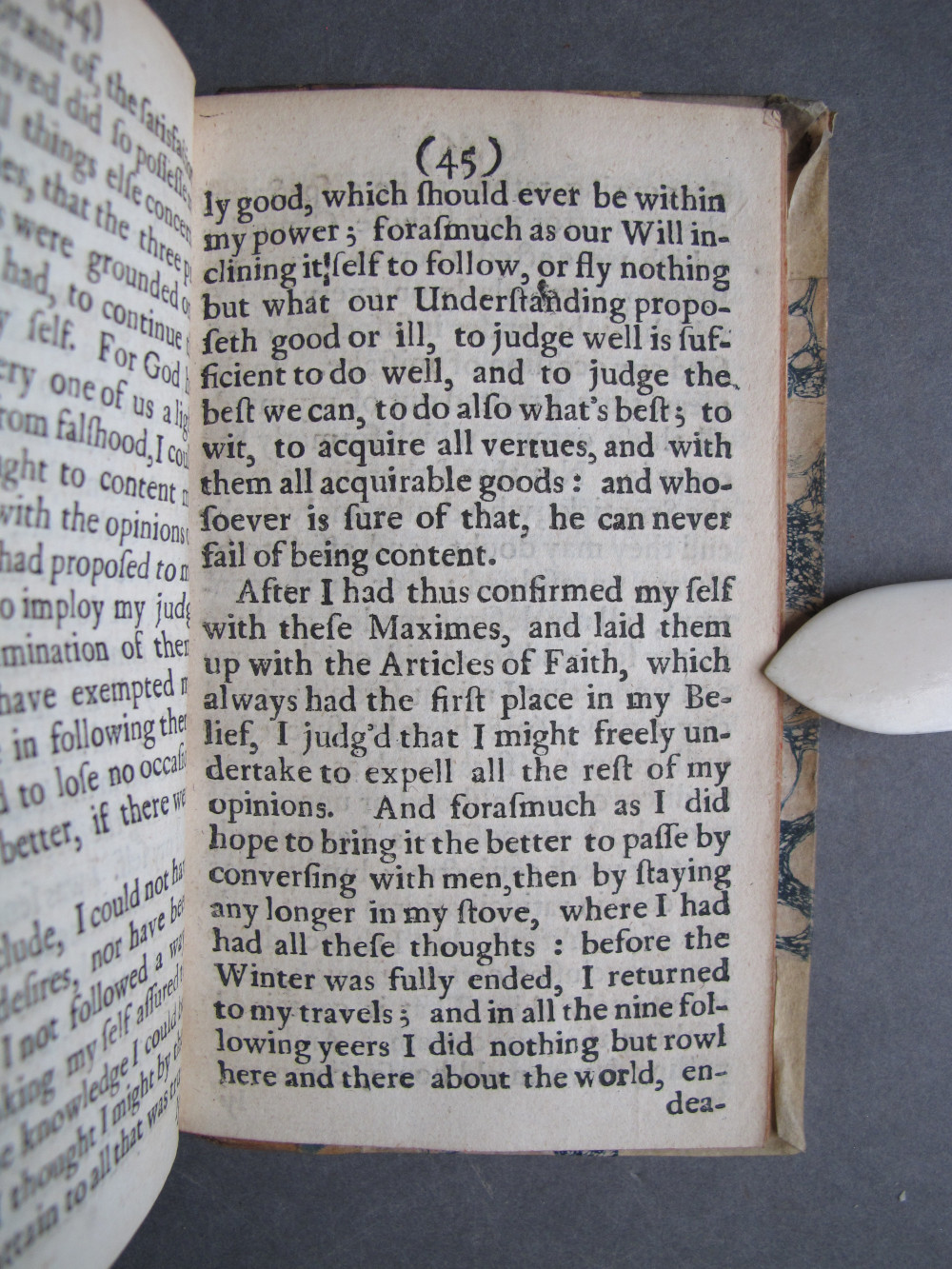

[Image 63 / 152]

(Page 45)

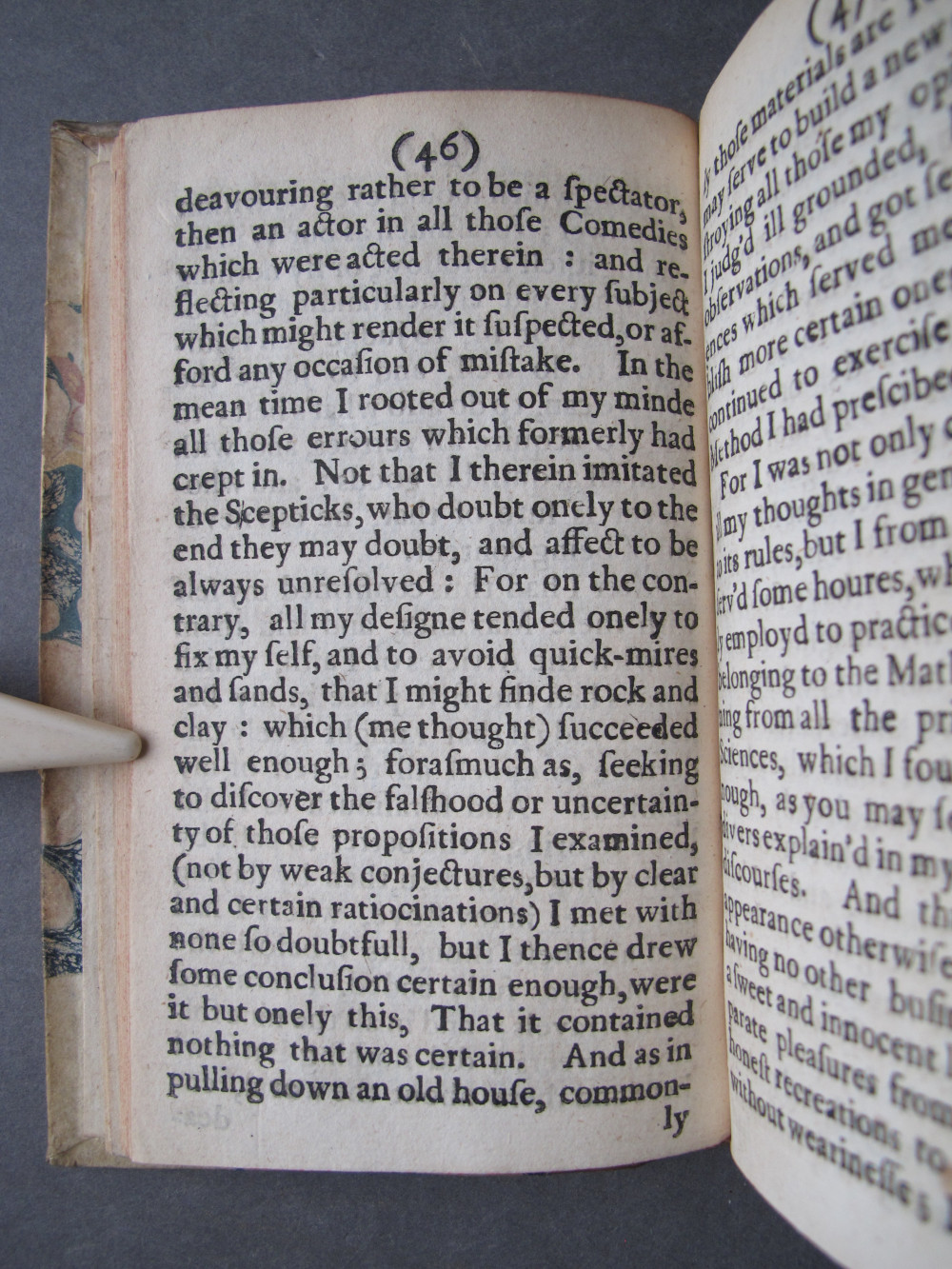

[Image 64 / 152]

(Page 46)

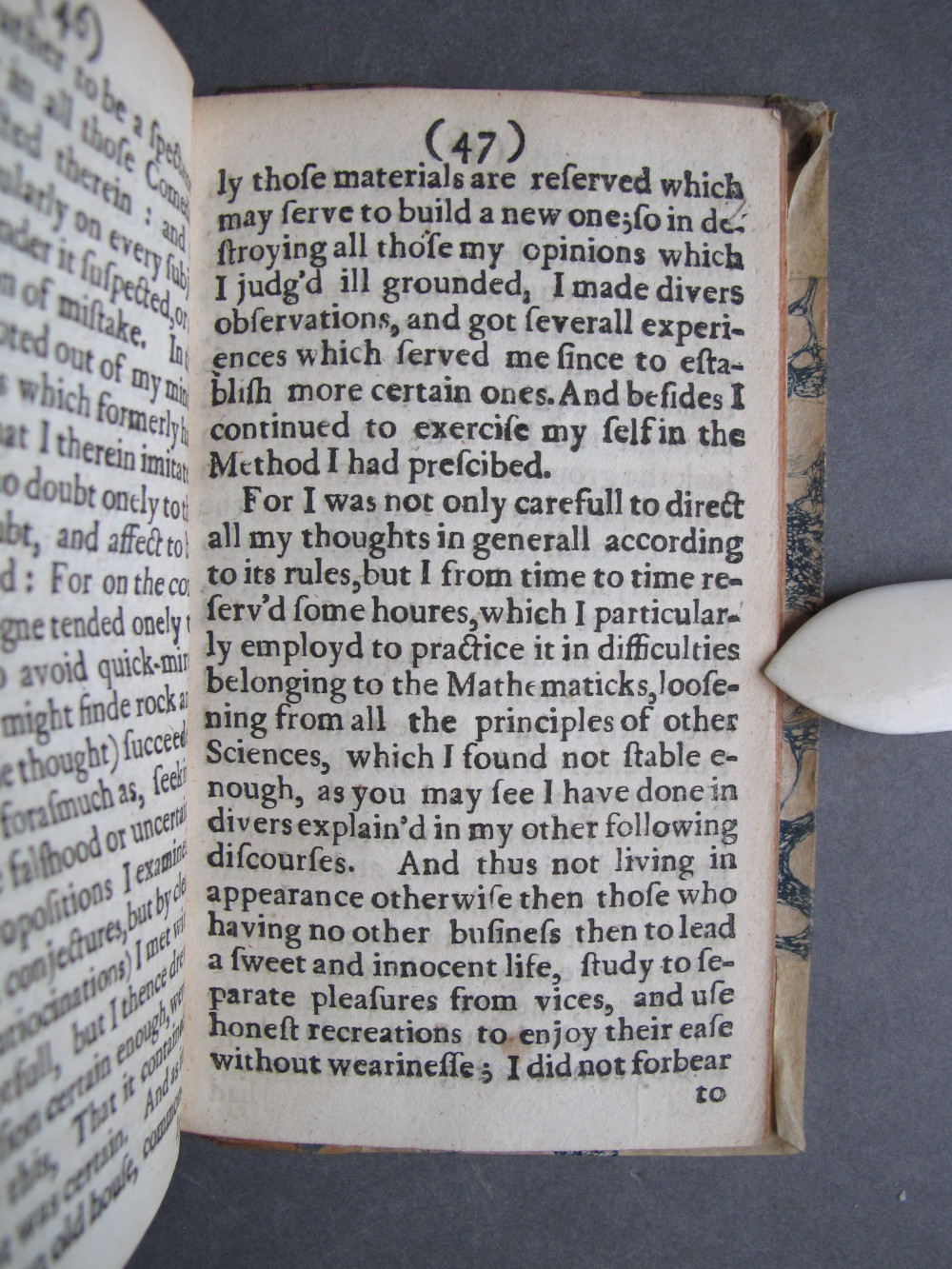

[Image 65 / 152]

(Page 47)

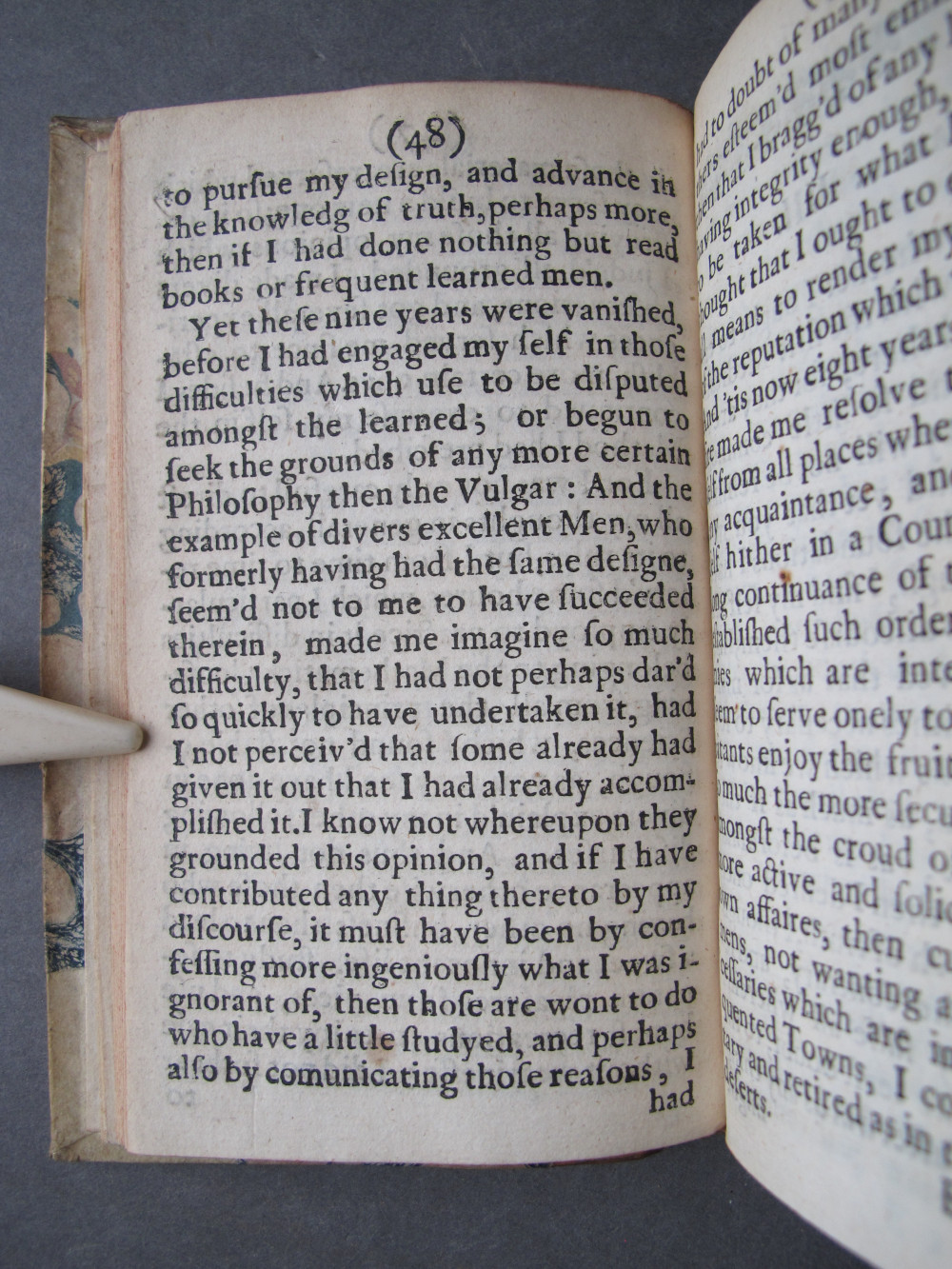

[Image 66 / 152]

(Page 48)

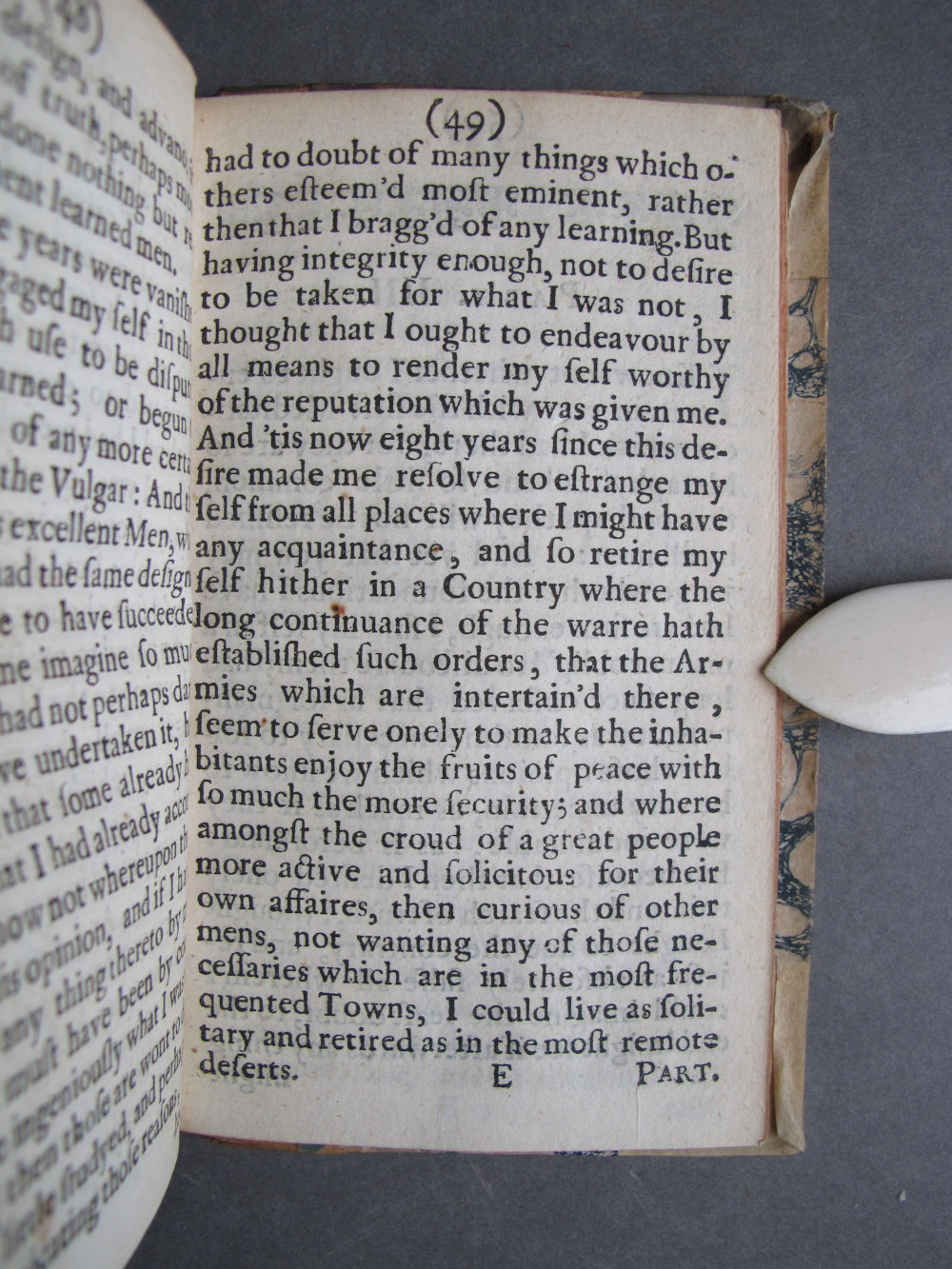

[Image 67 / 152]

(Page 49)

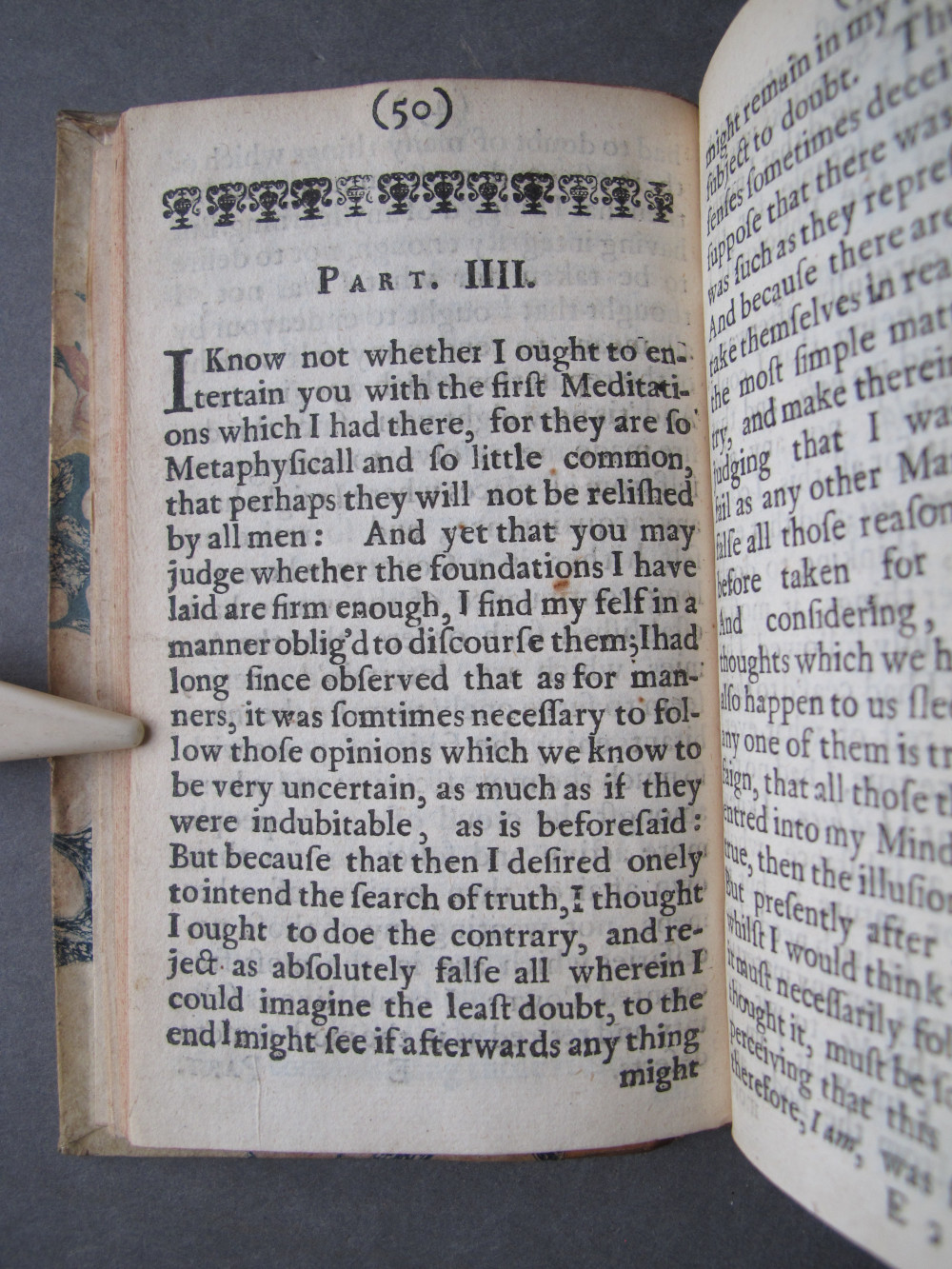

[Image 68 / 152]

(Page 50)

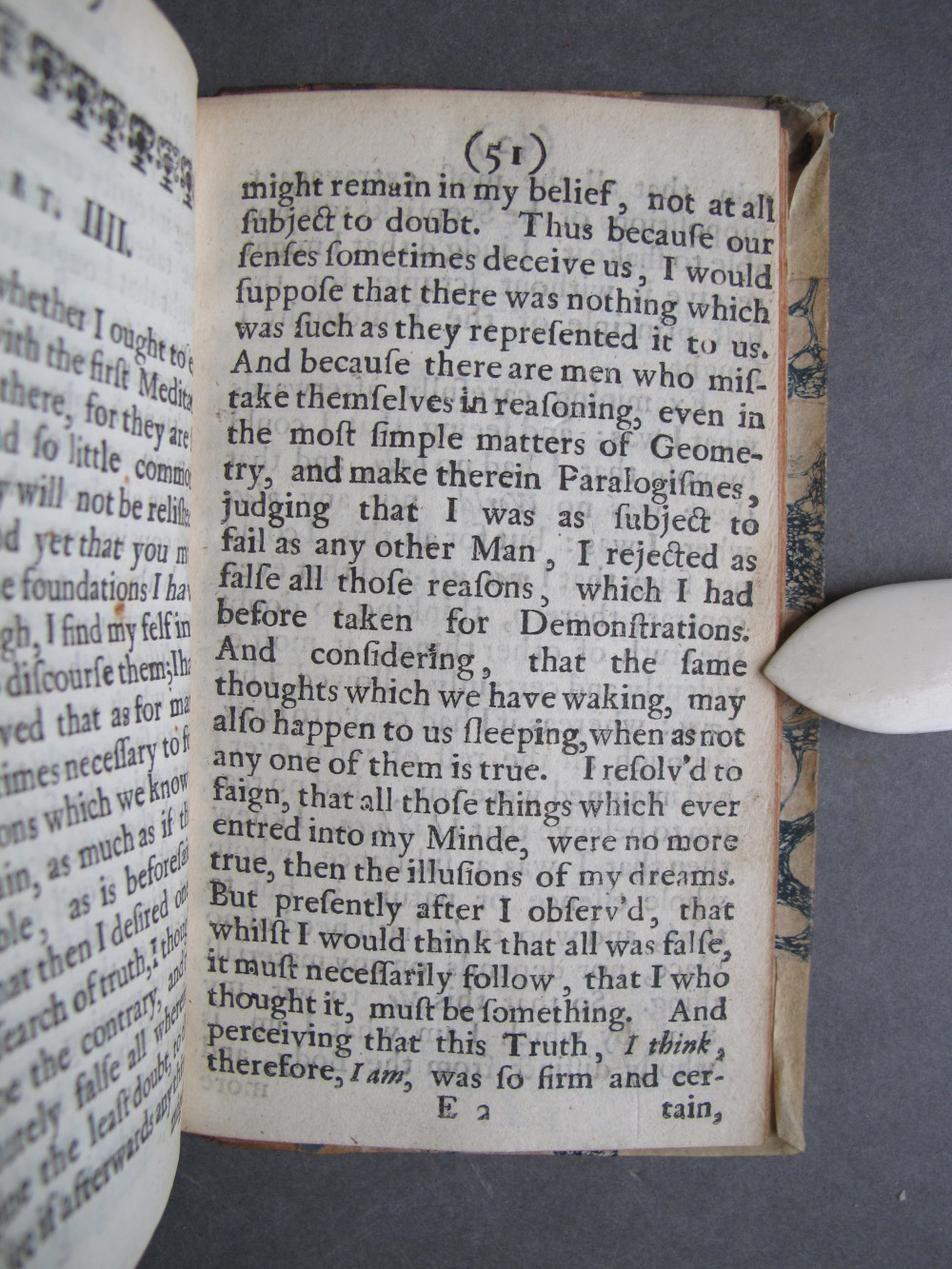

[Image 69 / 152]

(Page 51)

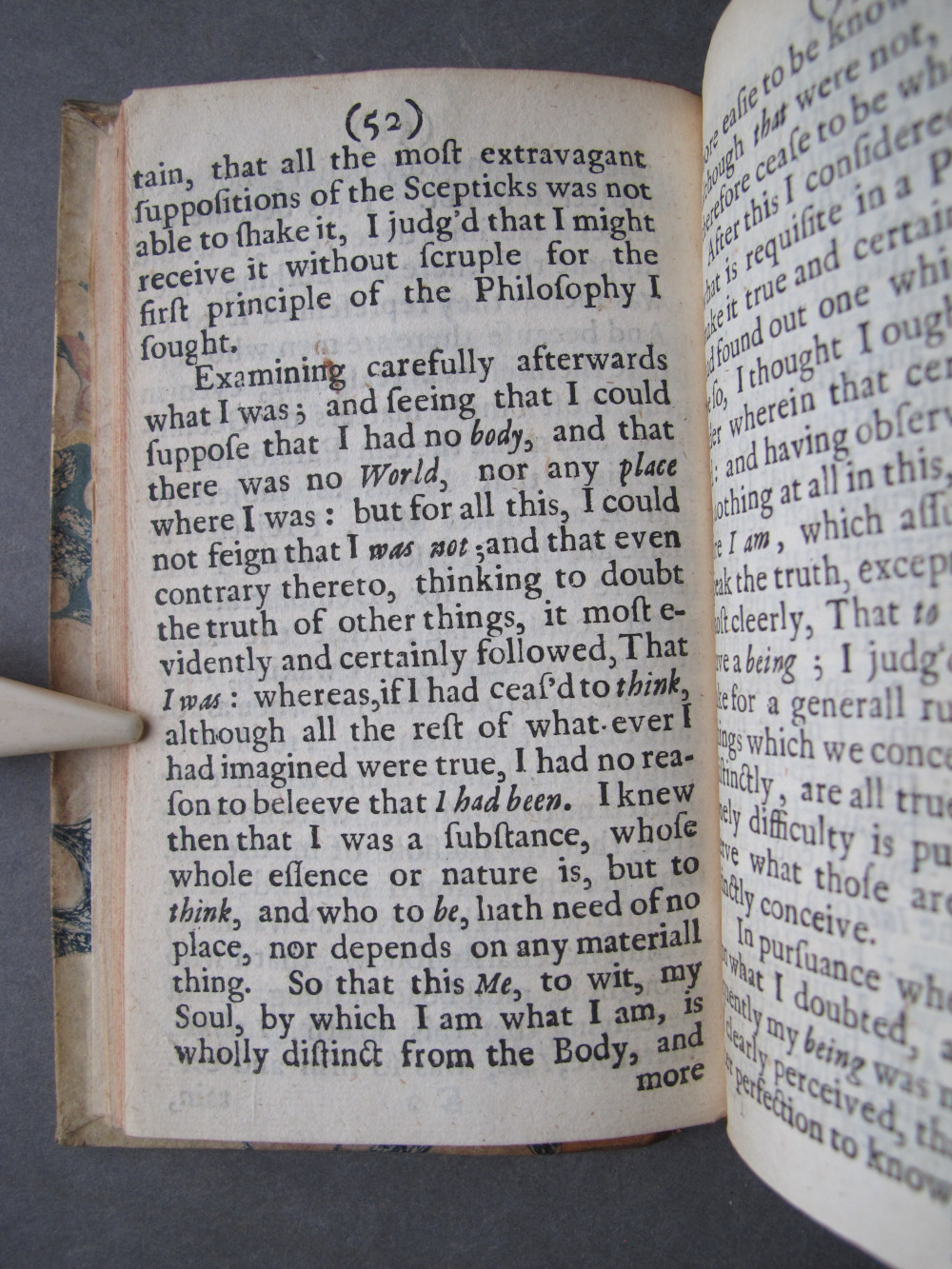

[Image 70 / 152]

(Page 52)

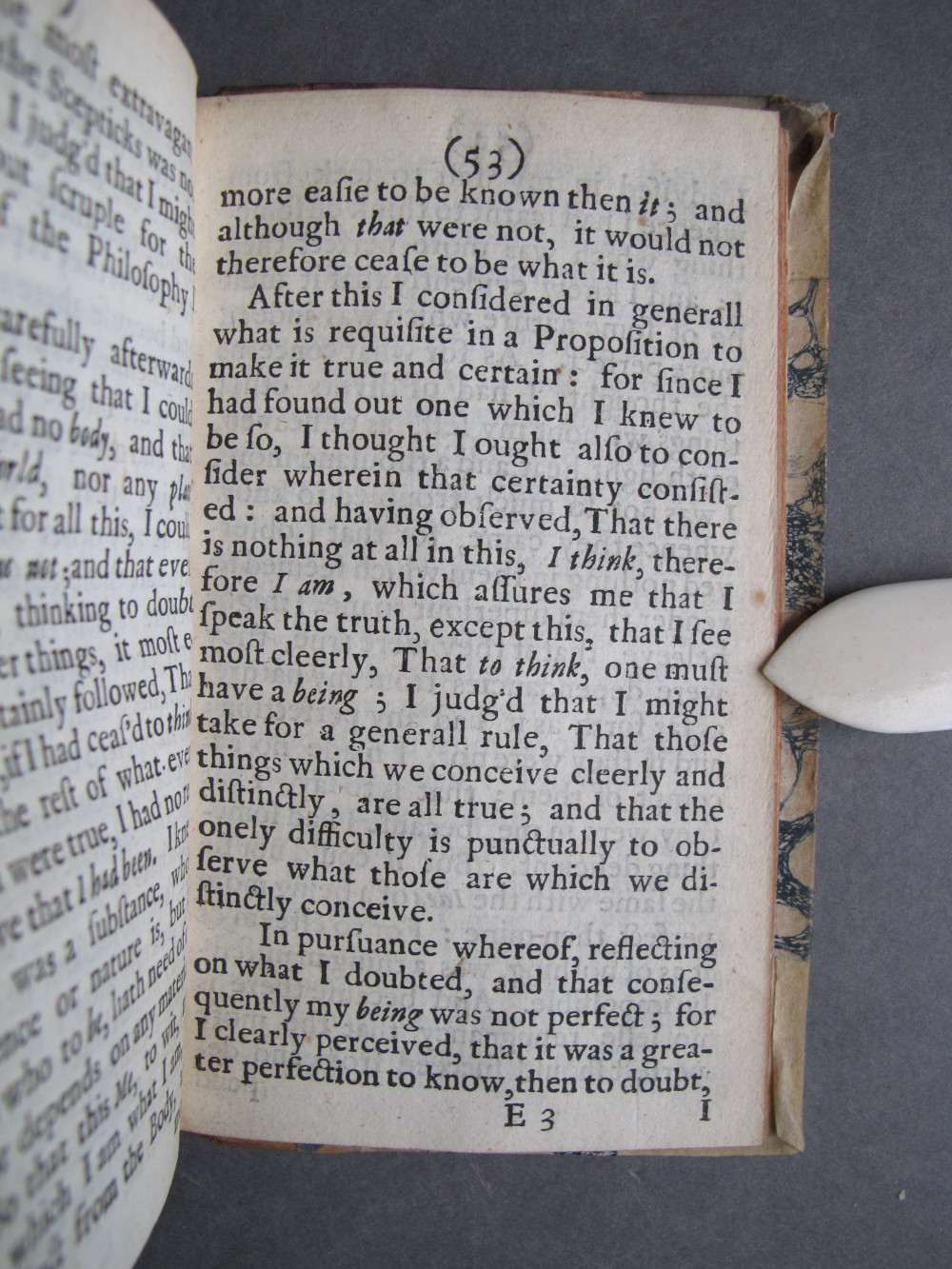

[Image 71 / 152]

(Page 53)

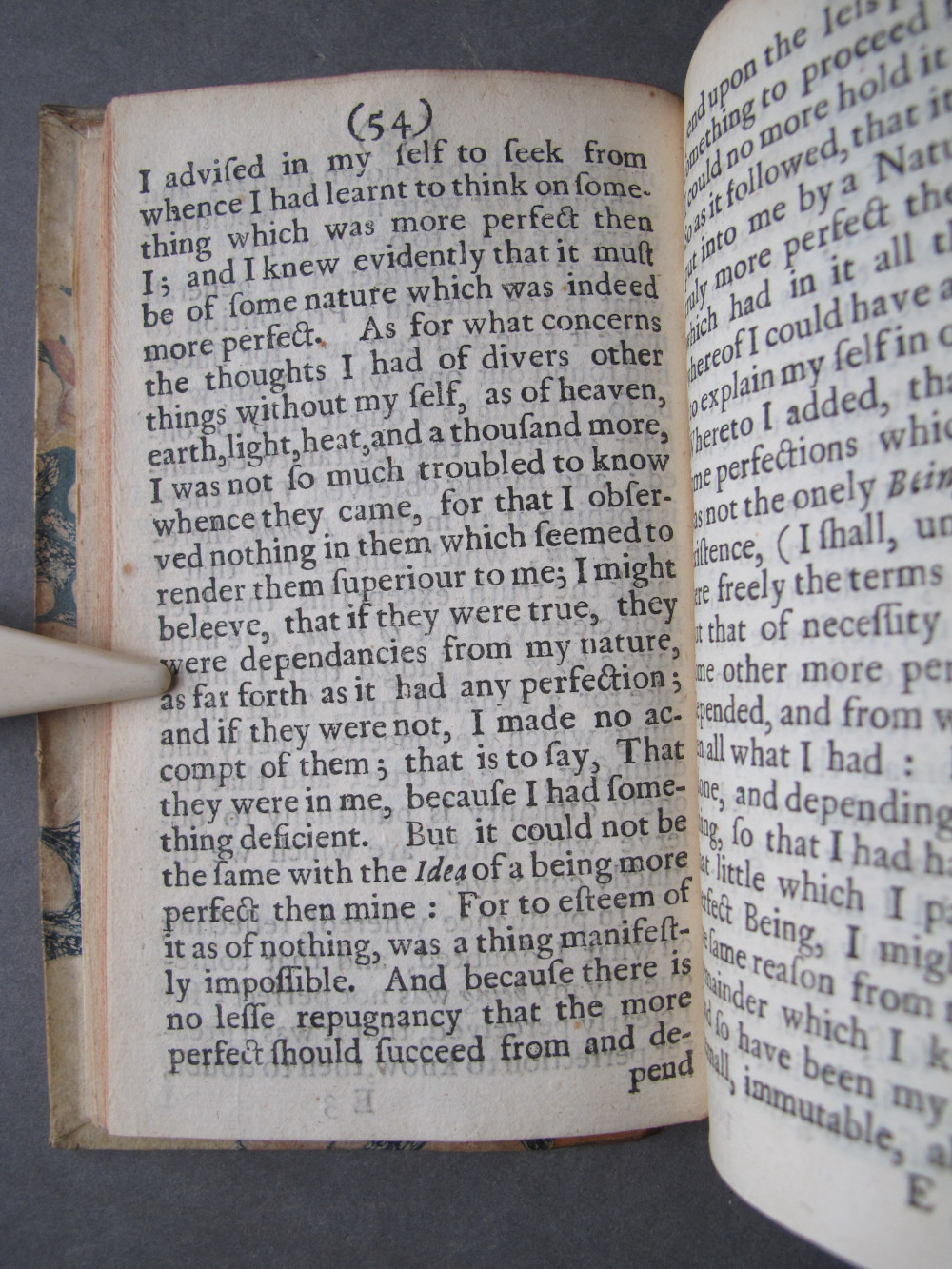

[Image 72 / 152]

(Page 54)

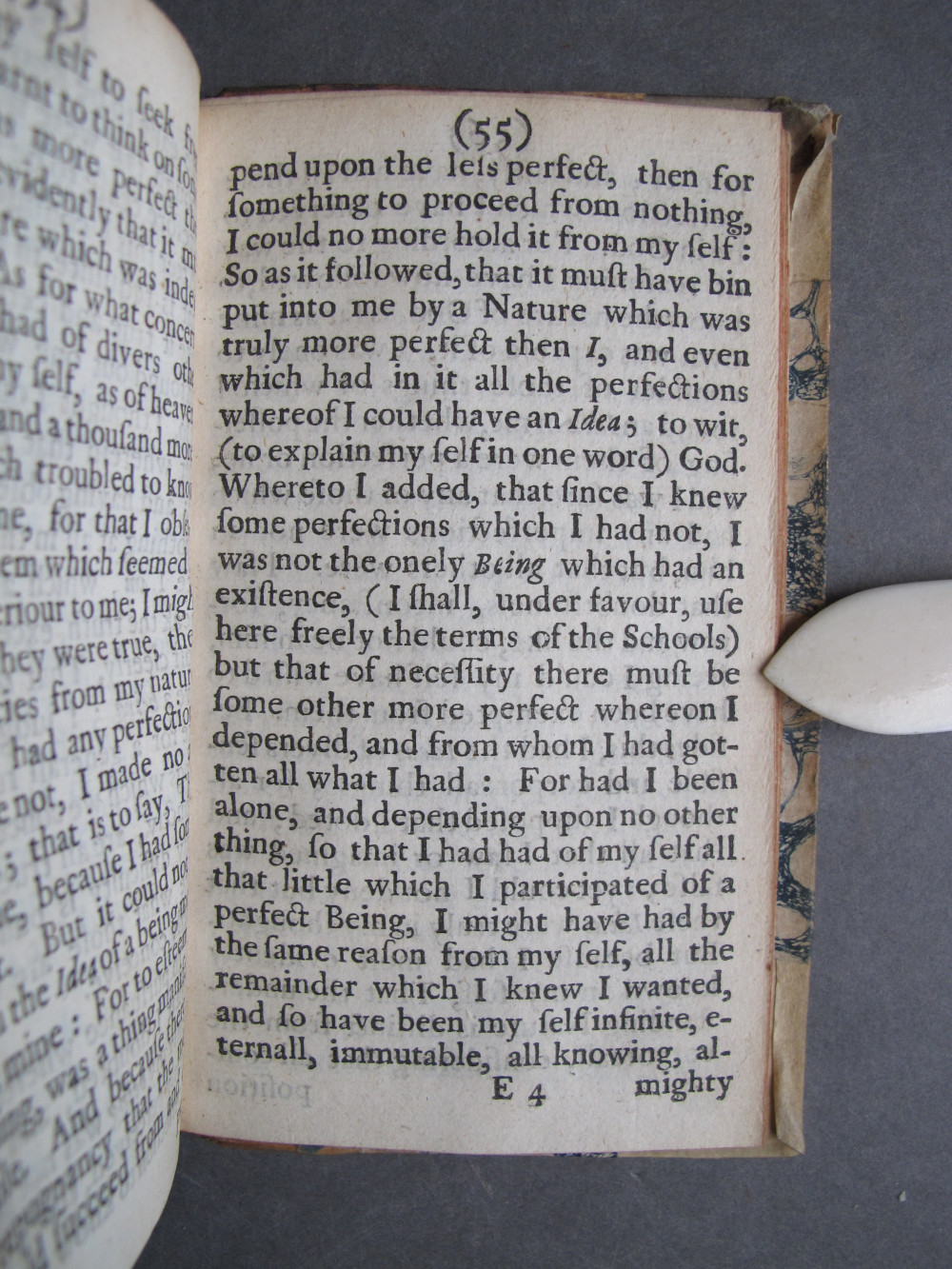

[Image 73 / 152]

(Page 55)

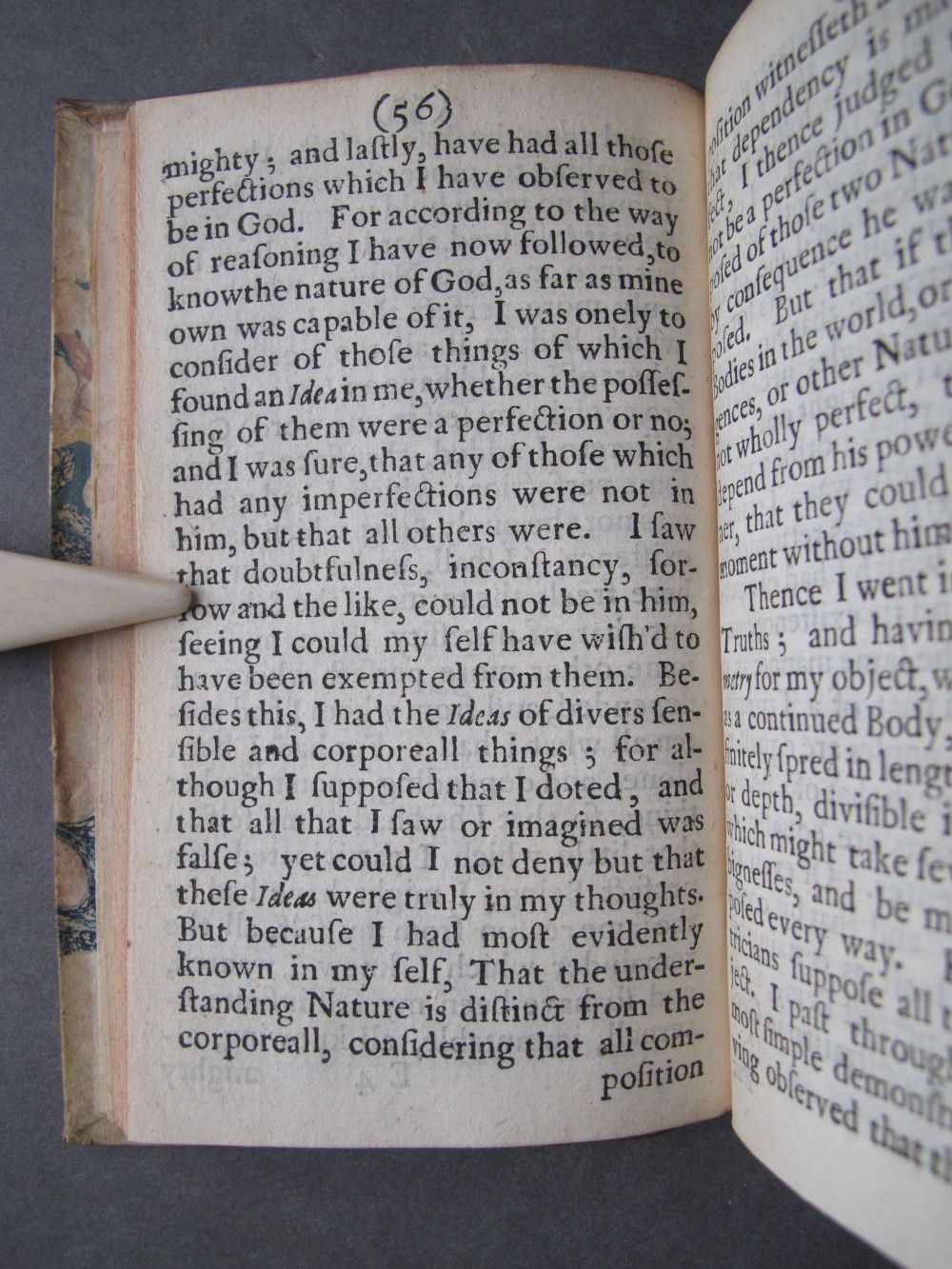

[Image 74 / 152]

(Page 56)

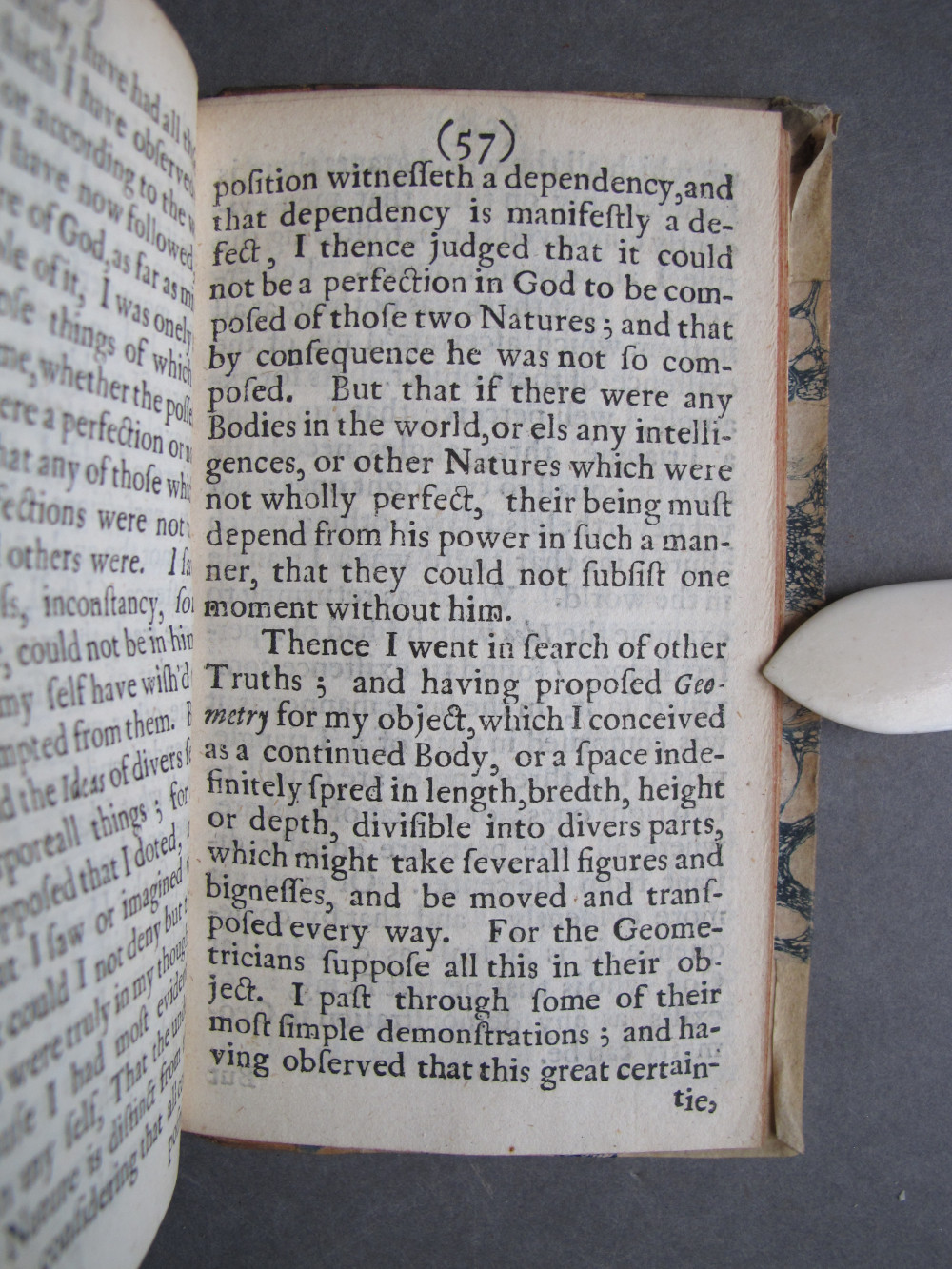

[Image 75 / 152]

(Page 57)

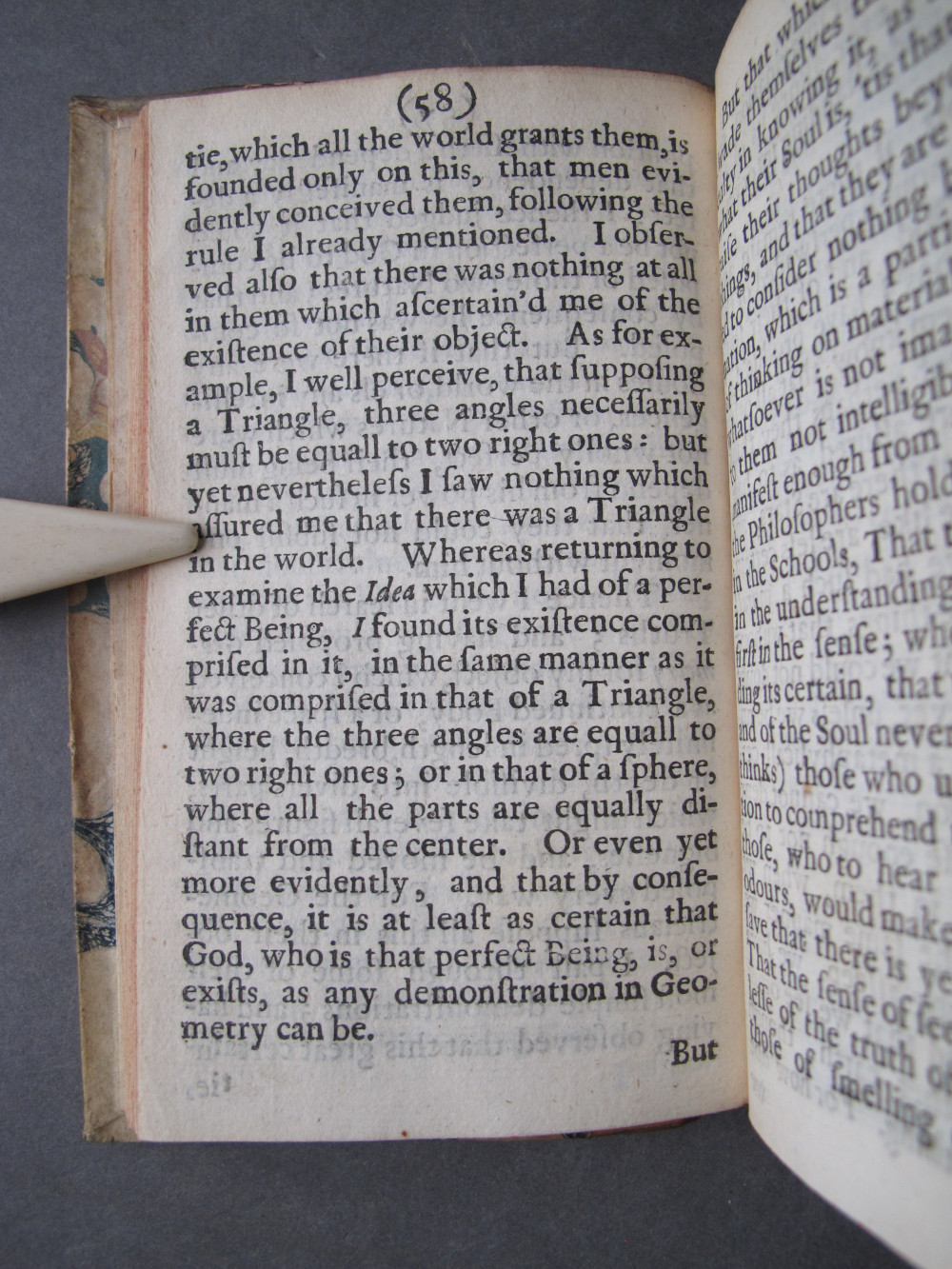

[Image 76 / 152]

(Page 58)

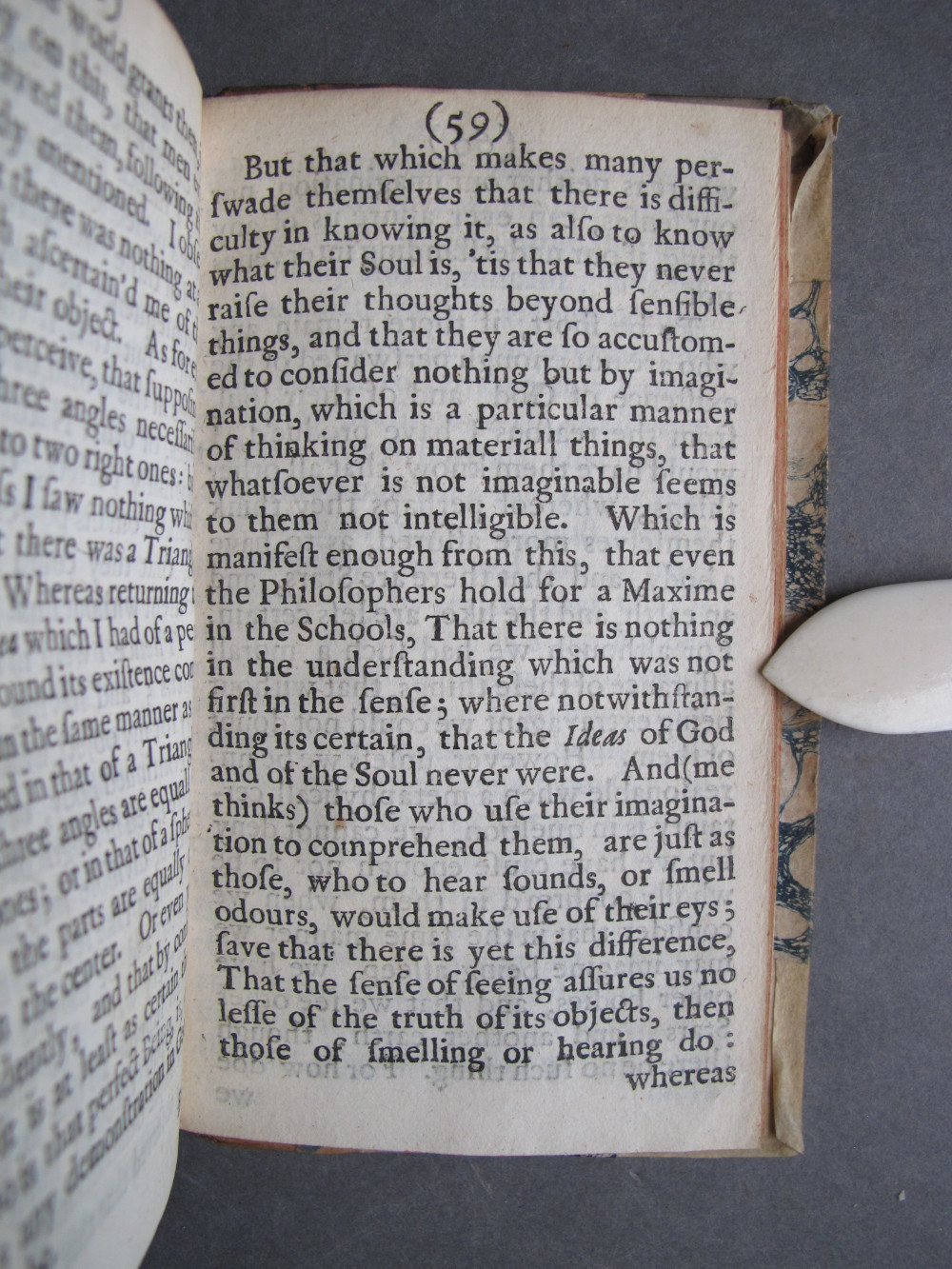

[Image 77 / 152]

(Page 59)

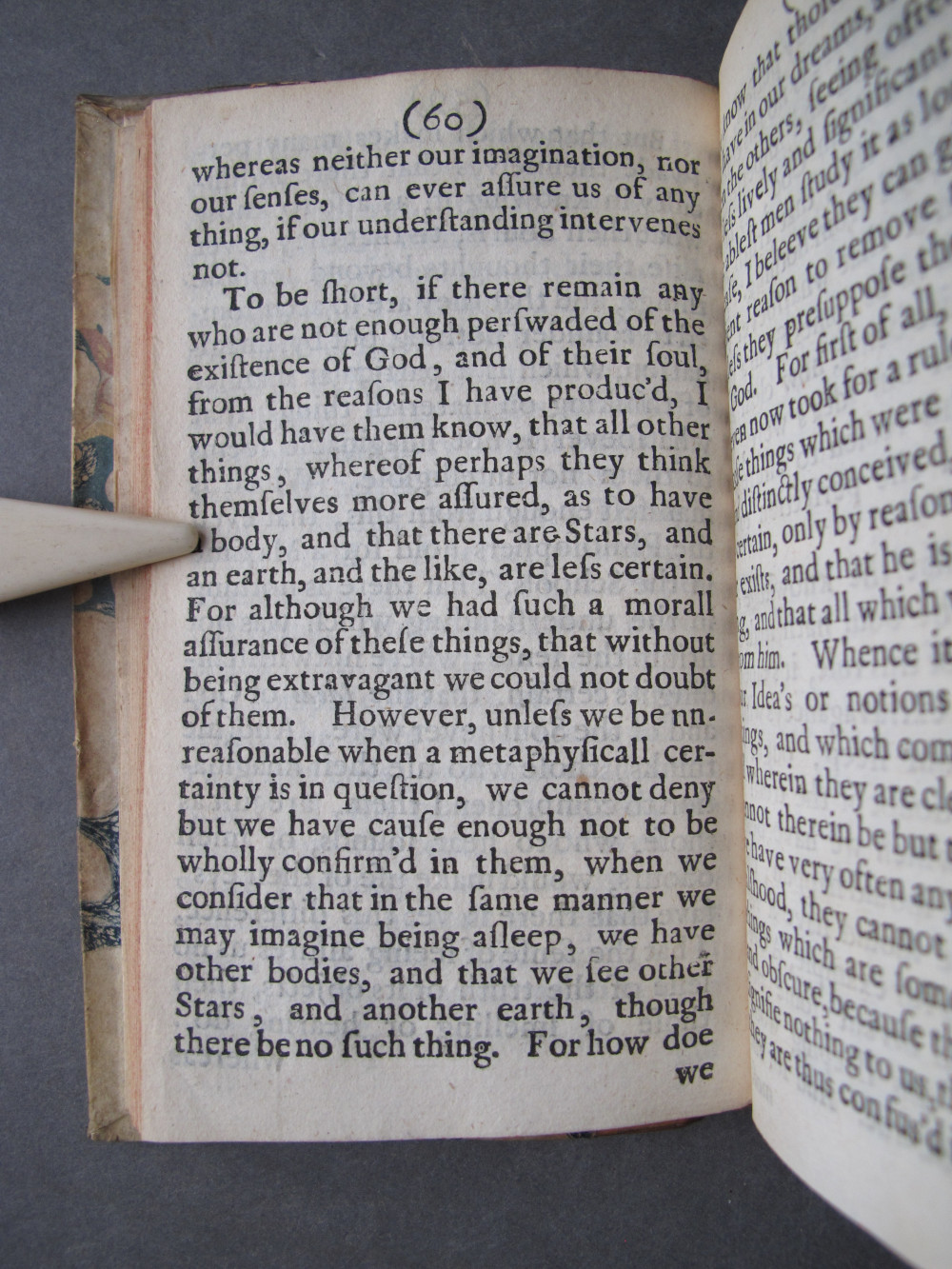

[Image 78 / 152]

(Page 60)

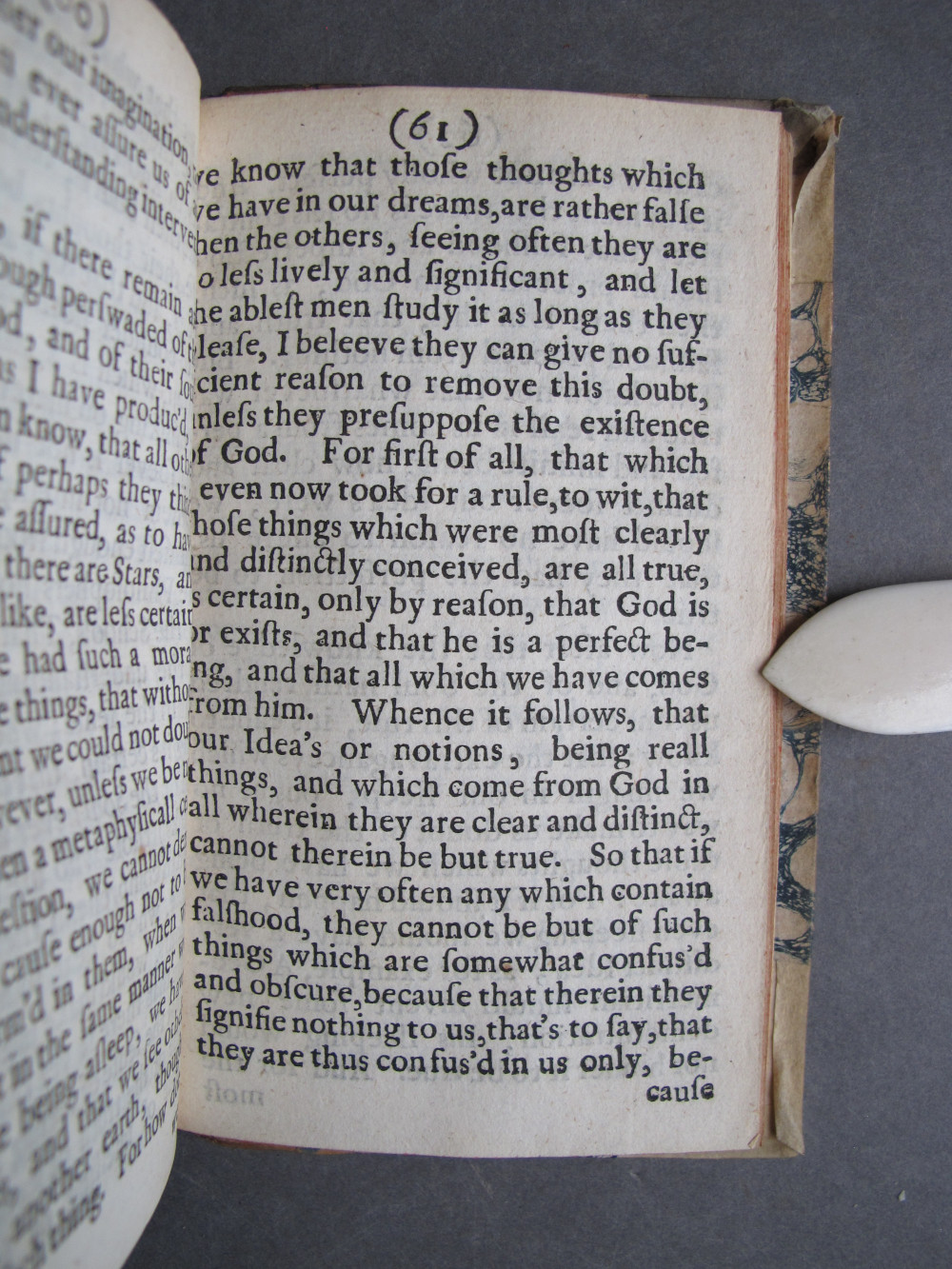

[Image 79 / 152]

(Page 61)

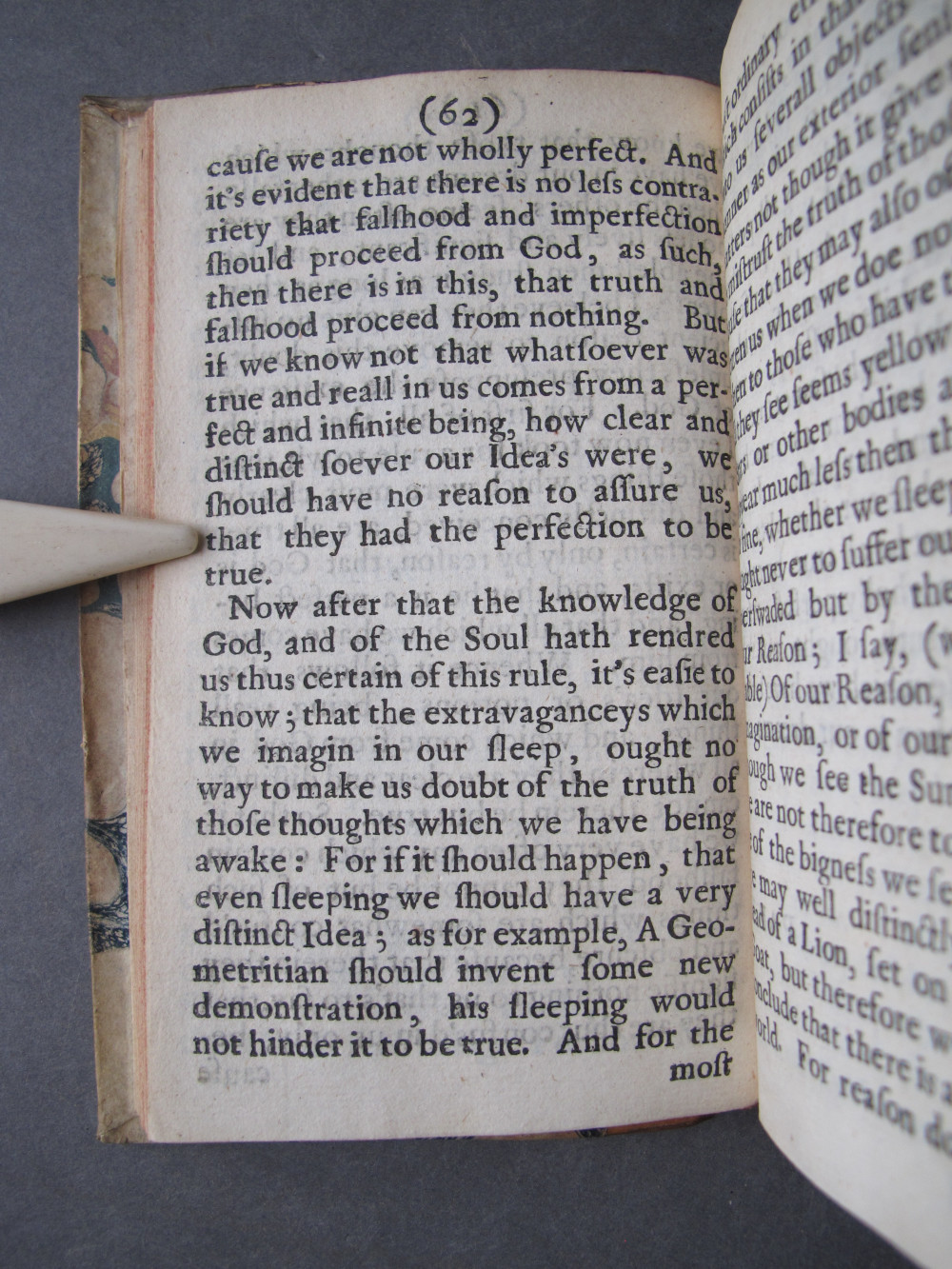

[Image 80 / 152]

(Page 62)

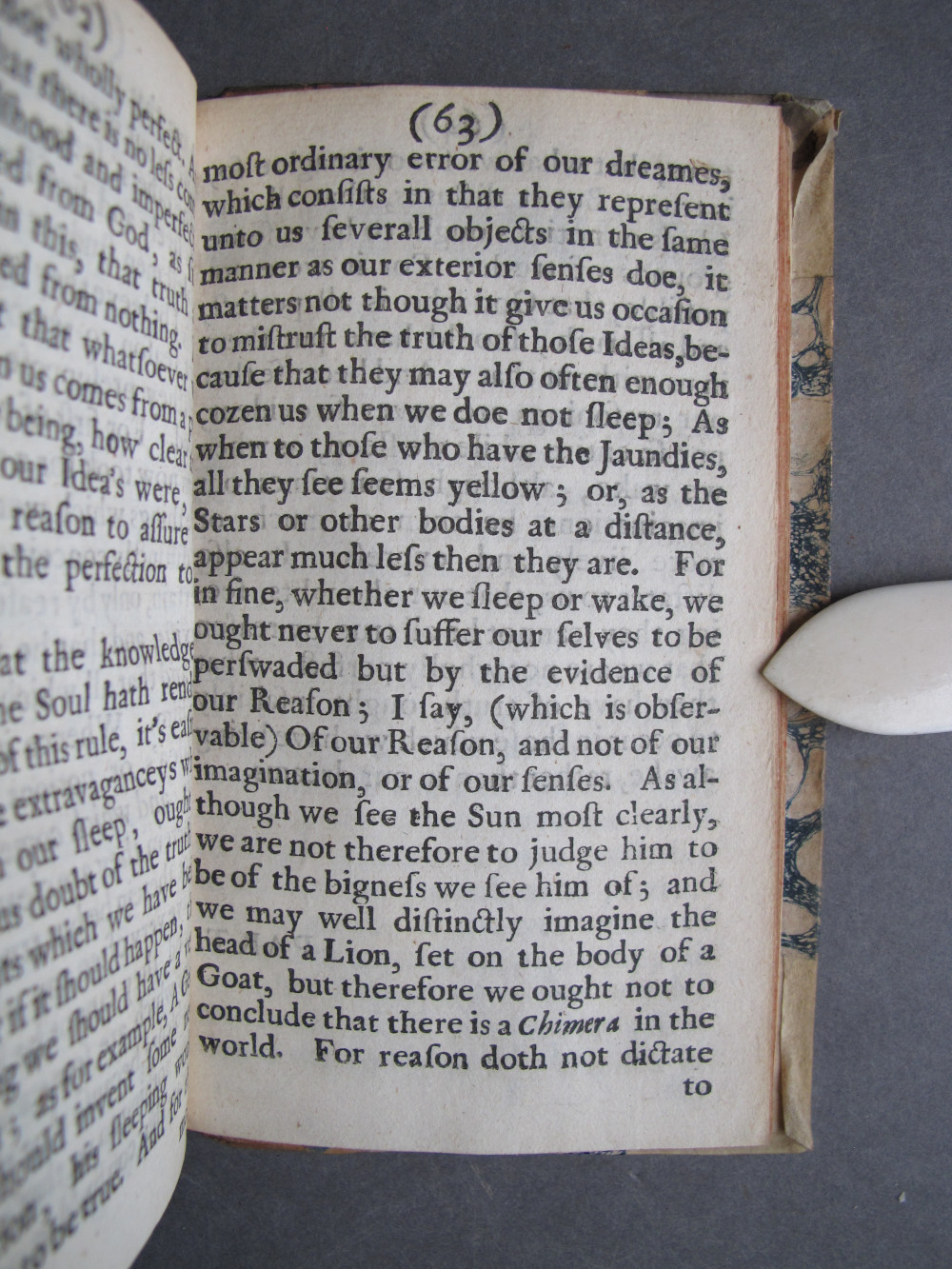

[Image 81 / 152]

(Page 63)

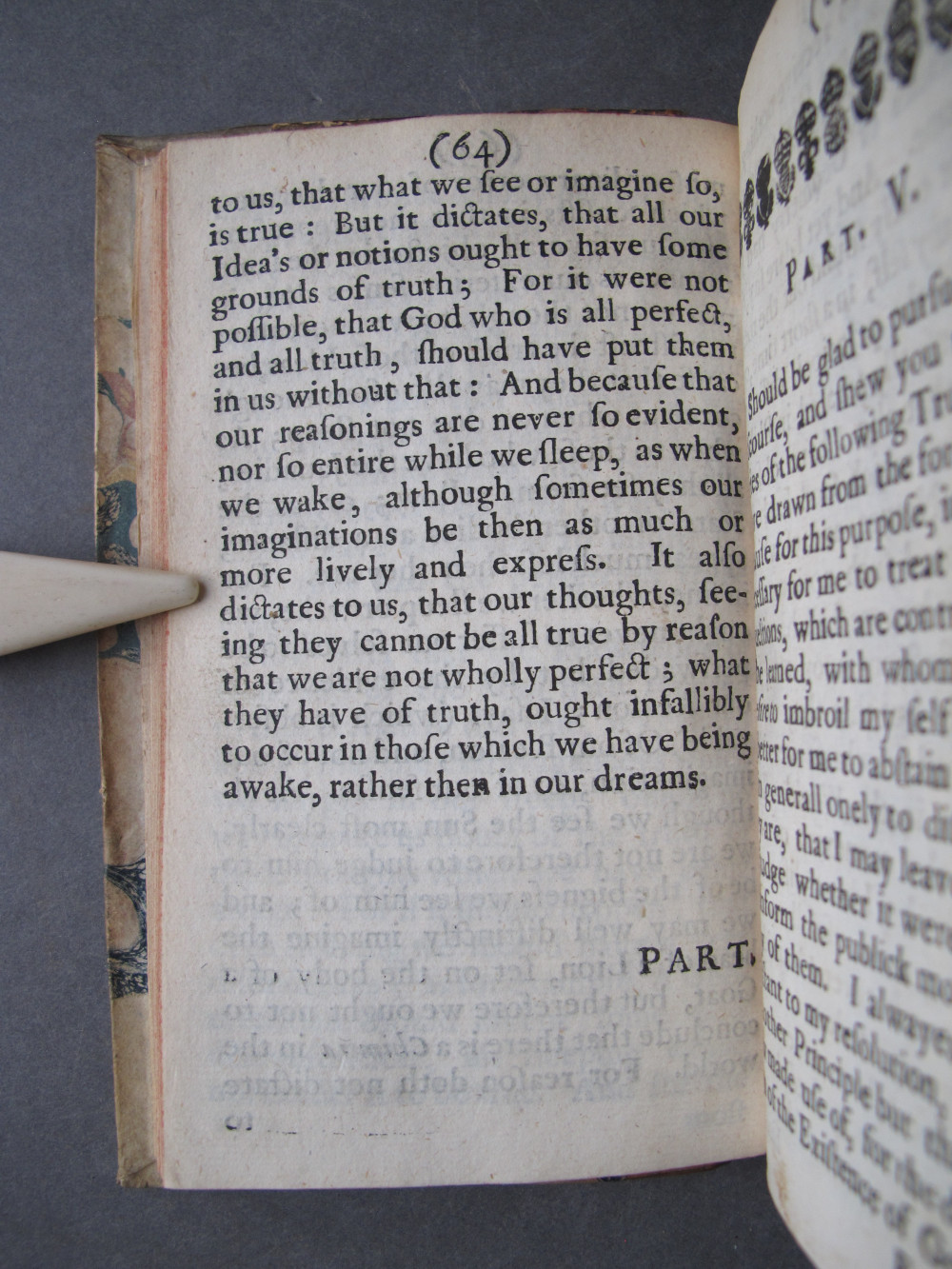

[Image 82 / 152]

(Page 64)

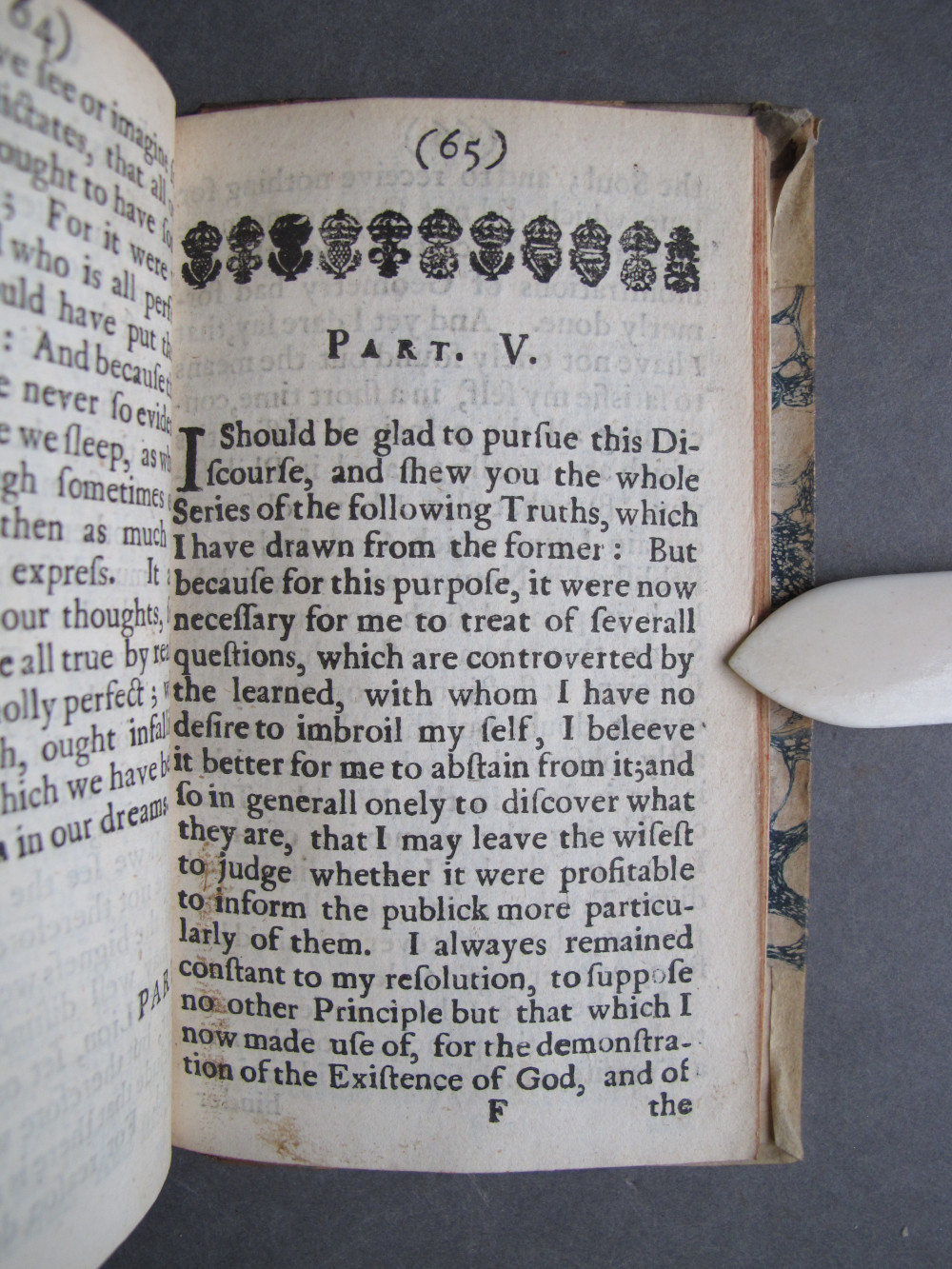

[Image 83 / 152]

(Page 65)

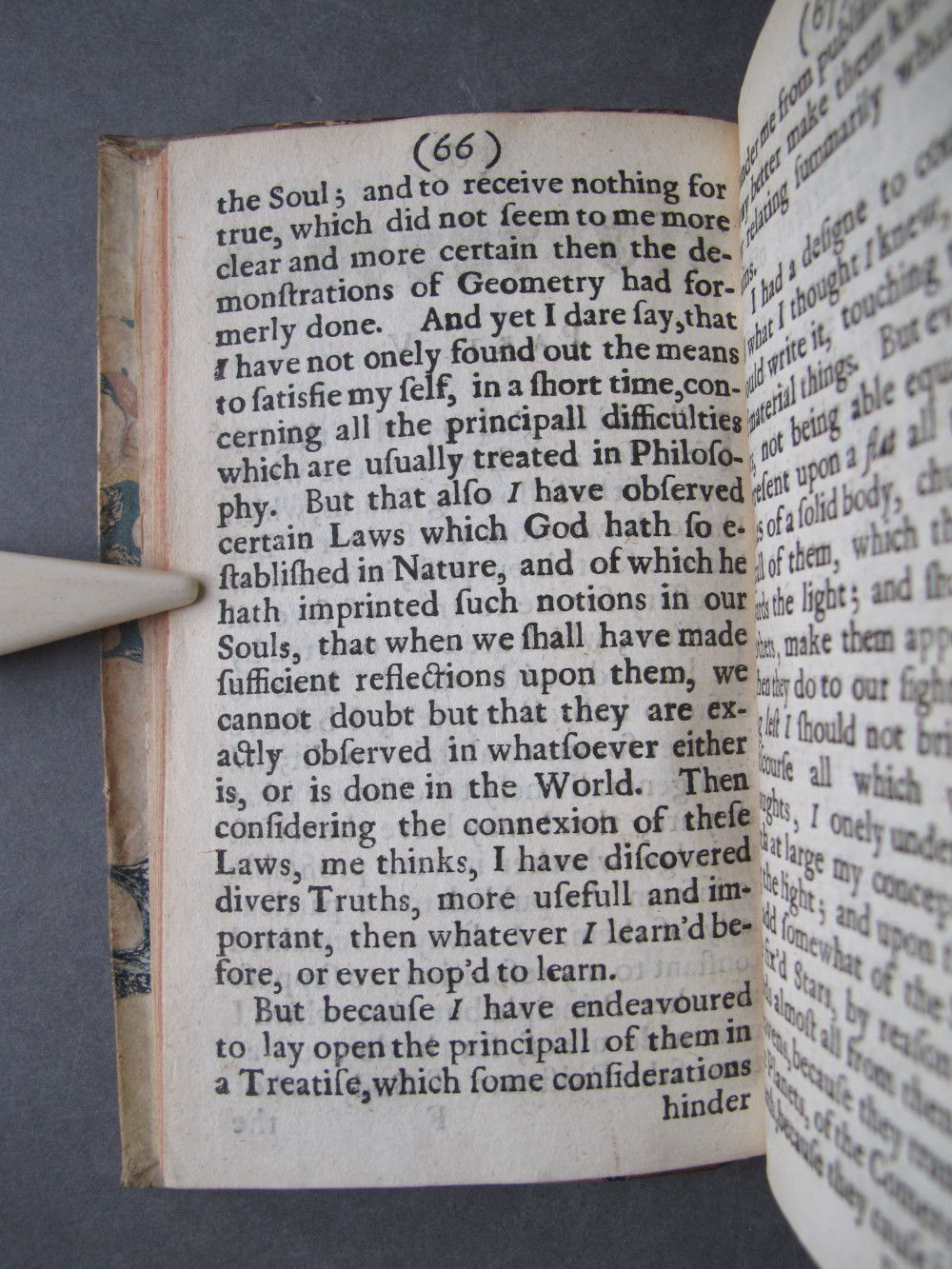

[Image 84 / 152]

(Page 66)

[Image 85 / 152]

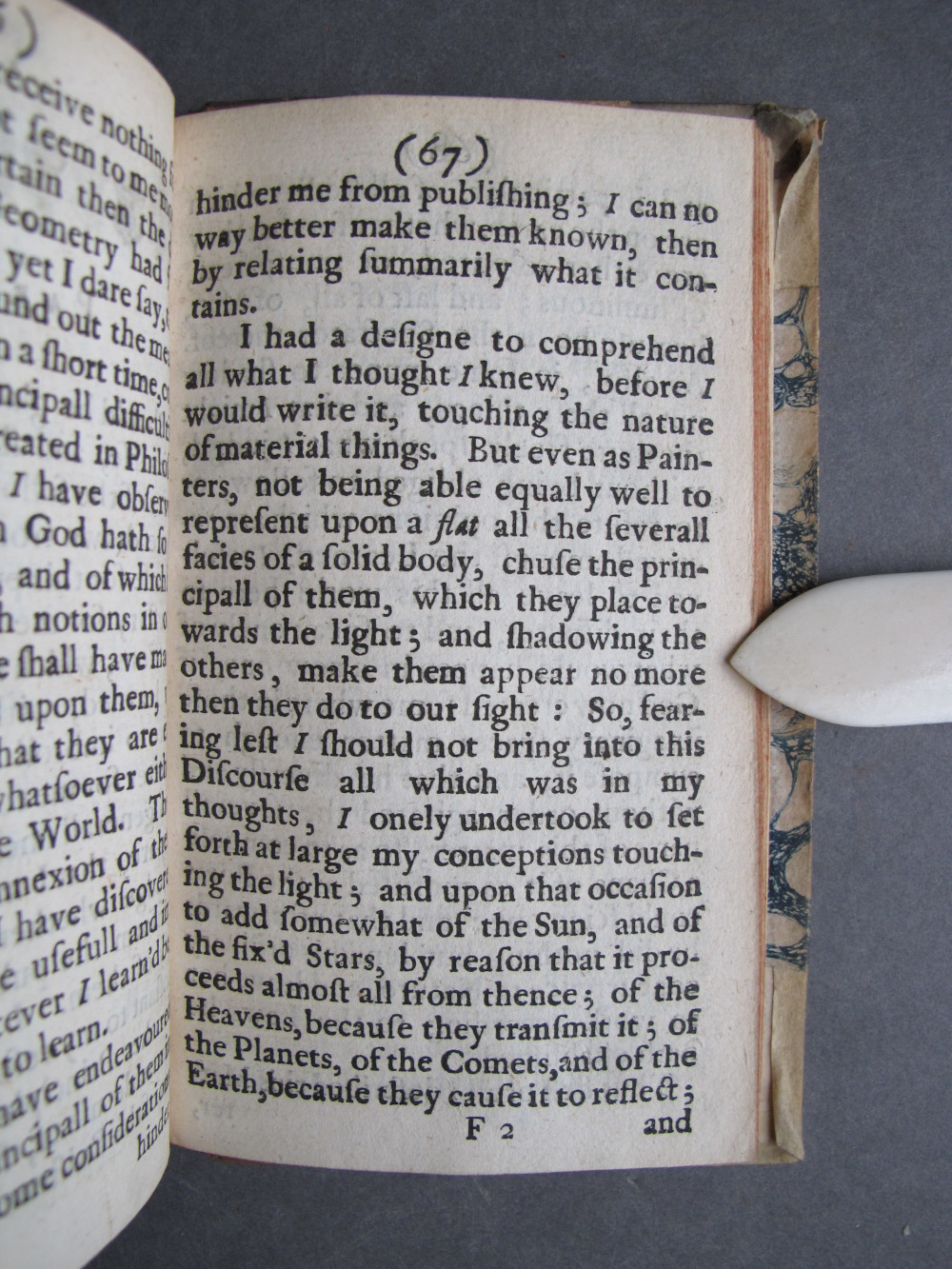

(Page 67)

[Image 86 / 152]

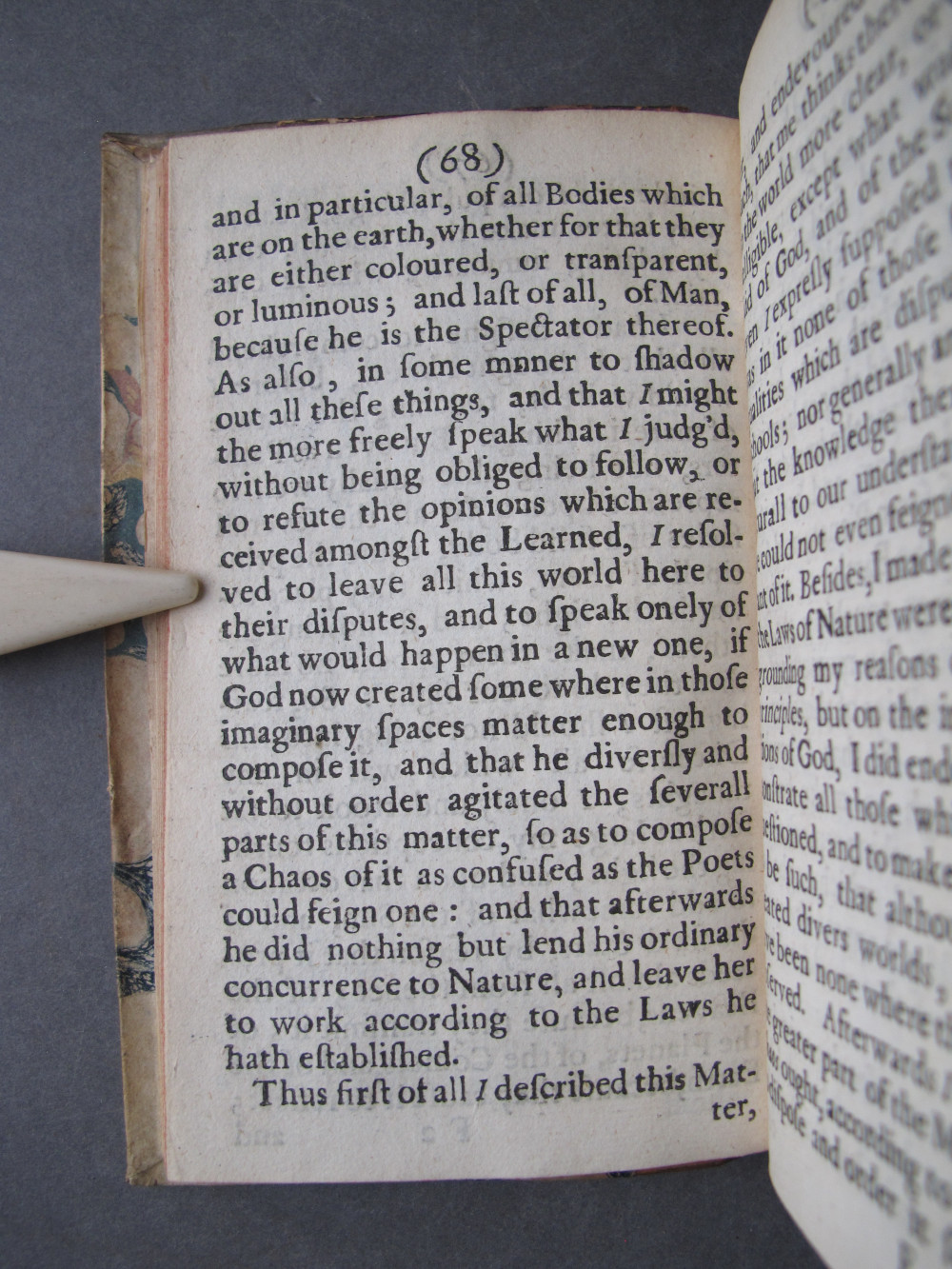

(Page 68)

[Image 87 / 152]

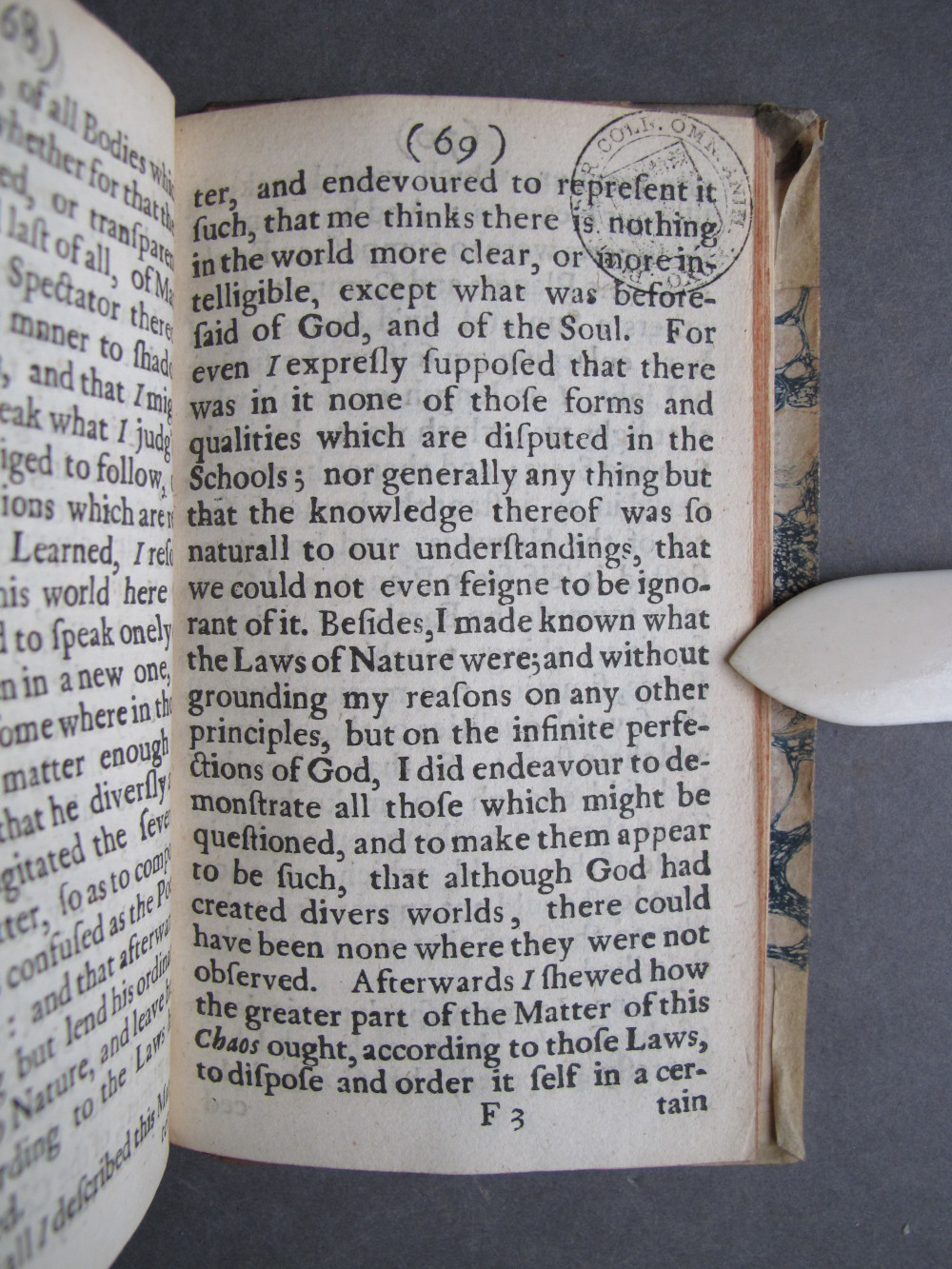

(Page 69)

[Image 88 / 152]

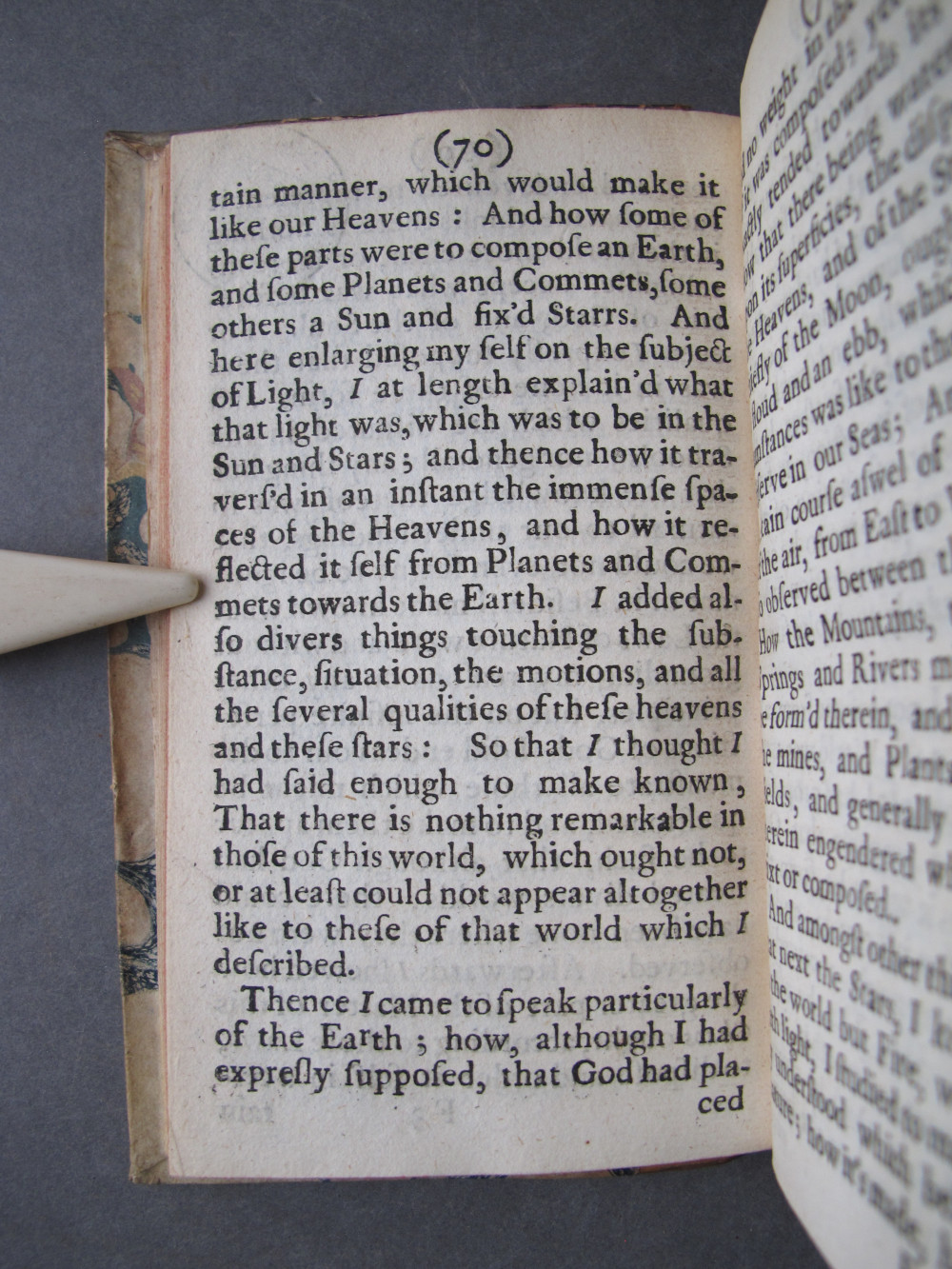

(Page 70)

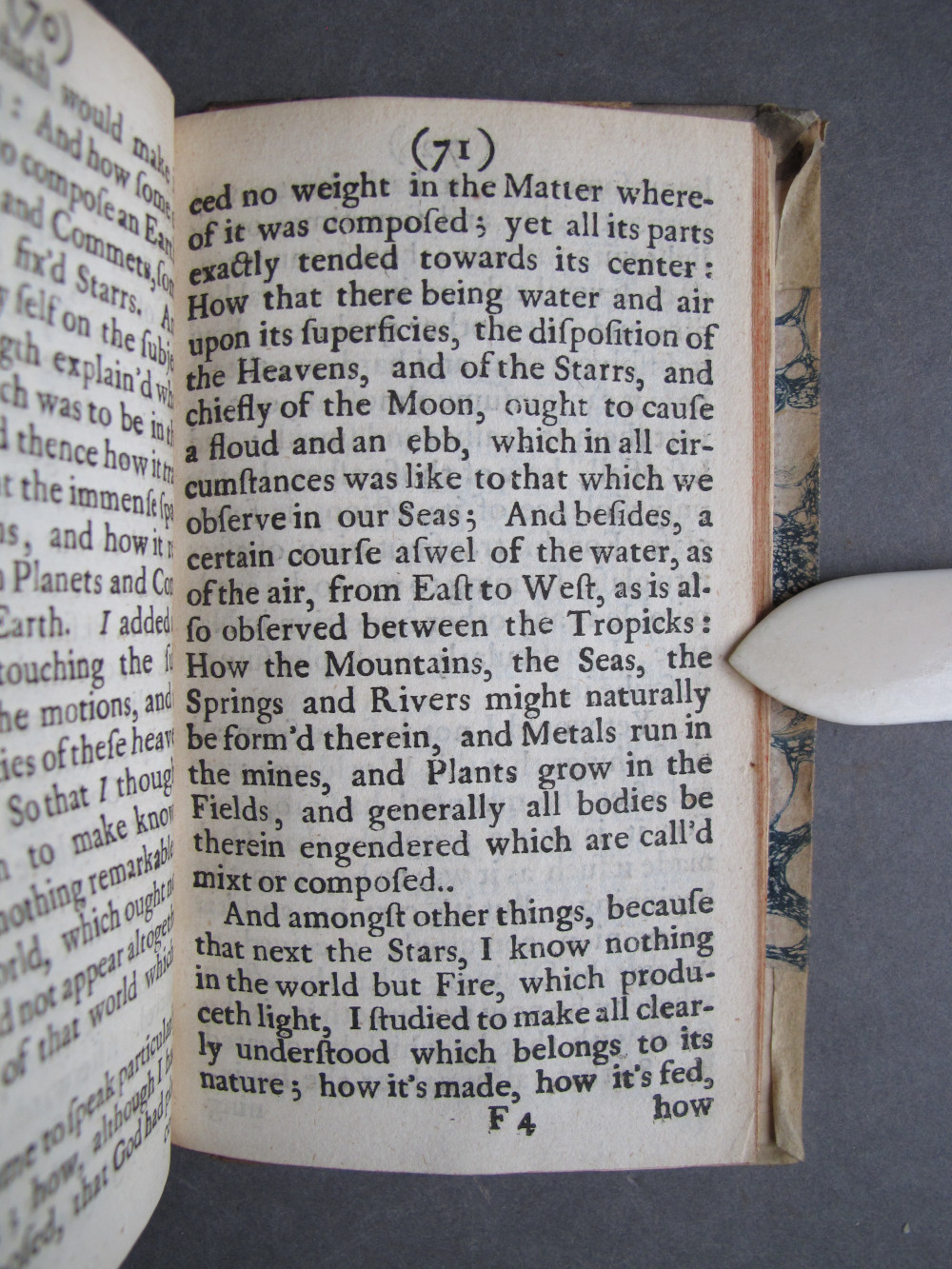

[Image 89 / 152]

(Page 71)

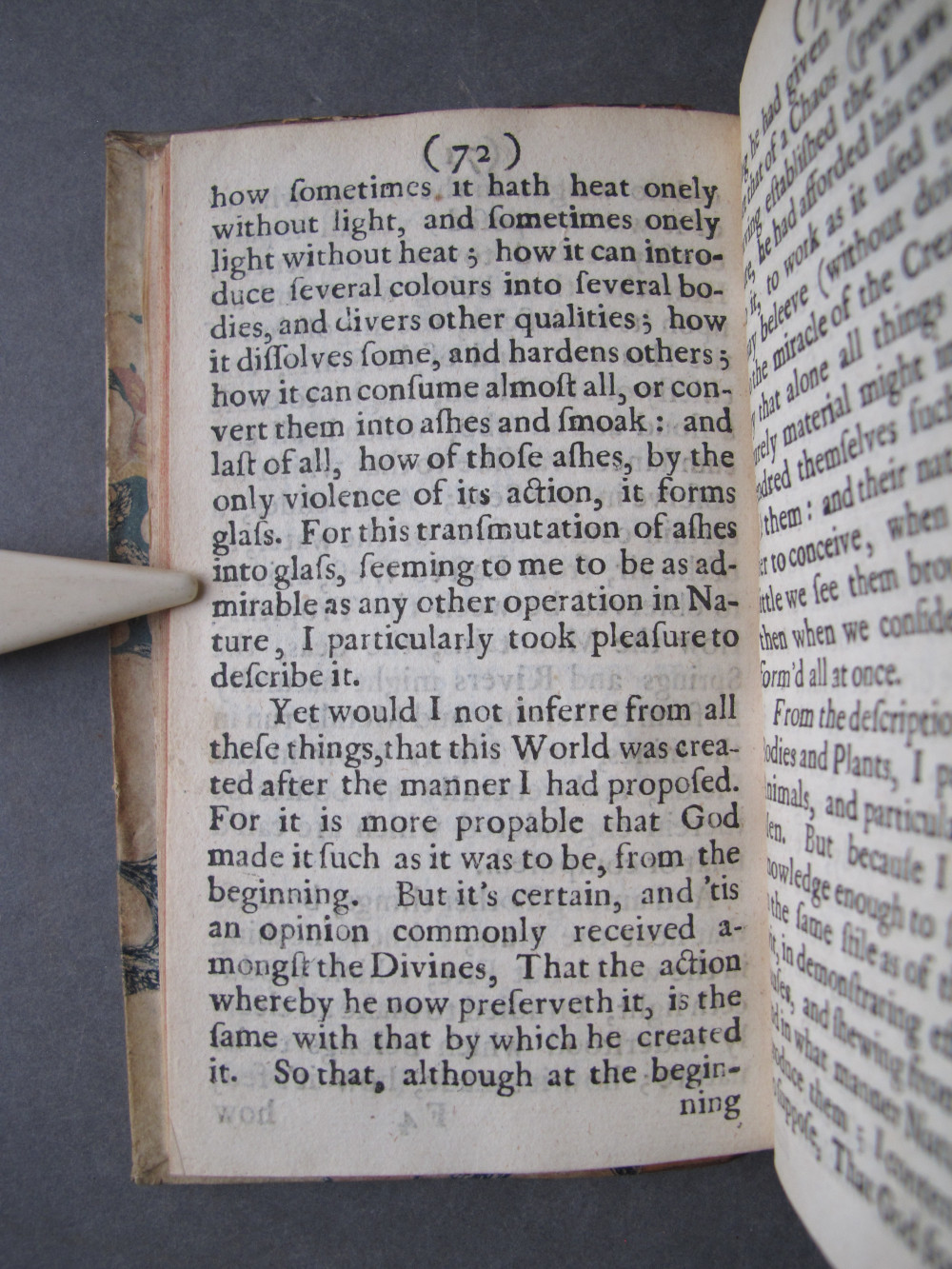

[Image 90 / 152]

(Page 72)

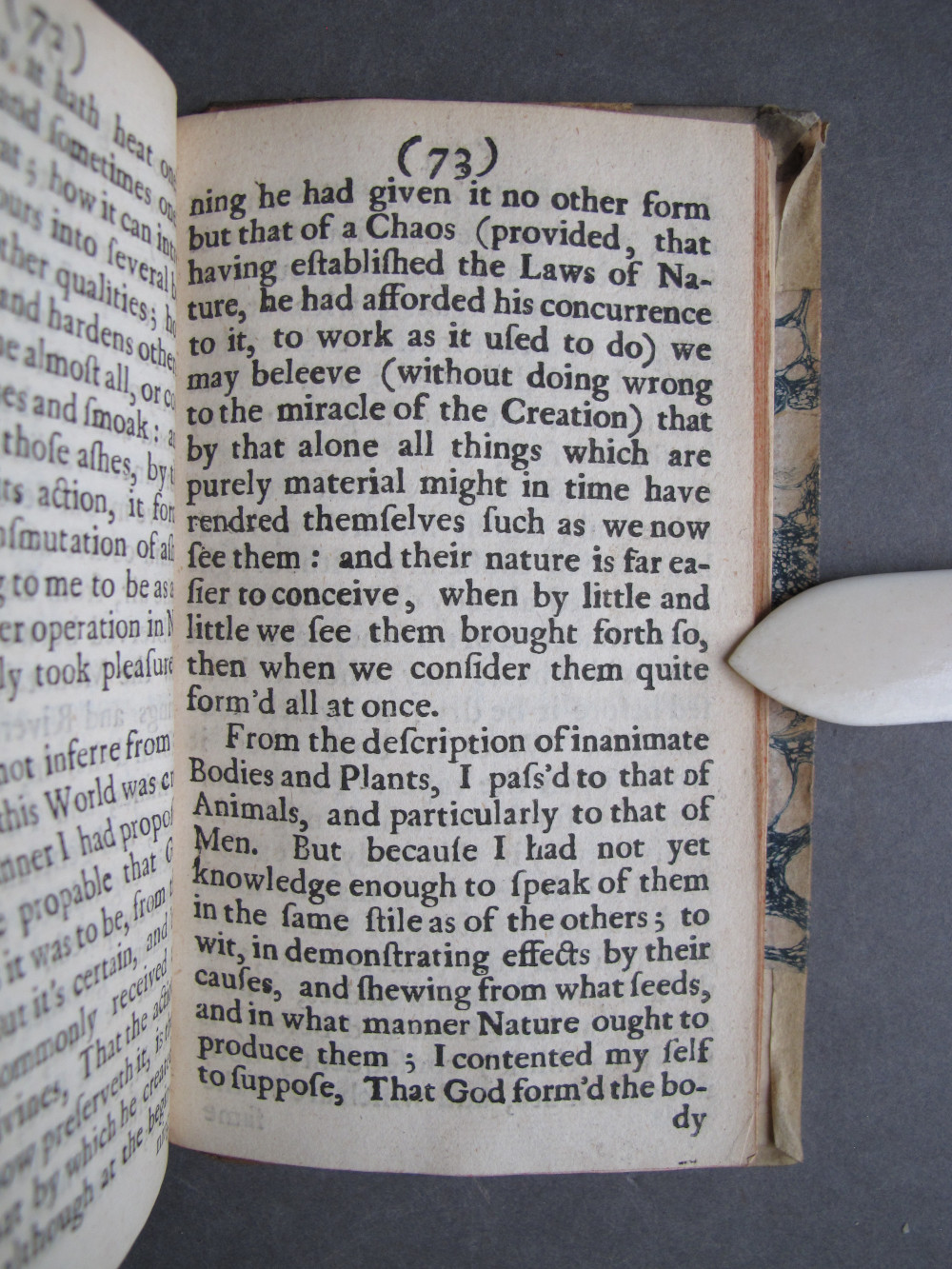

[Image 91 / 152]

(Page 73)

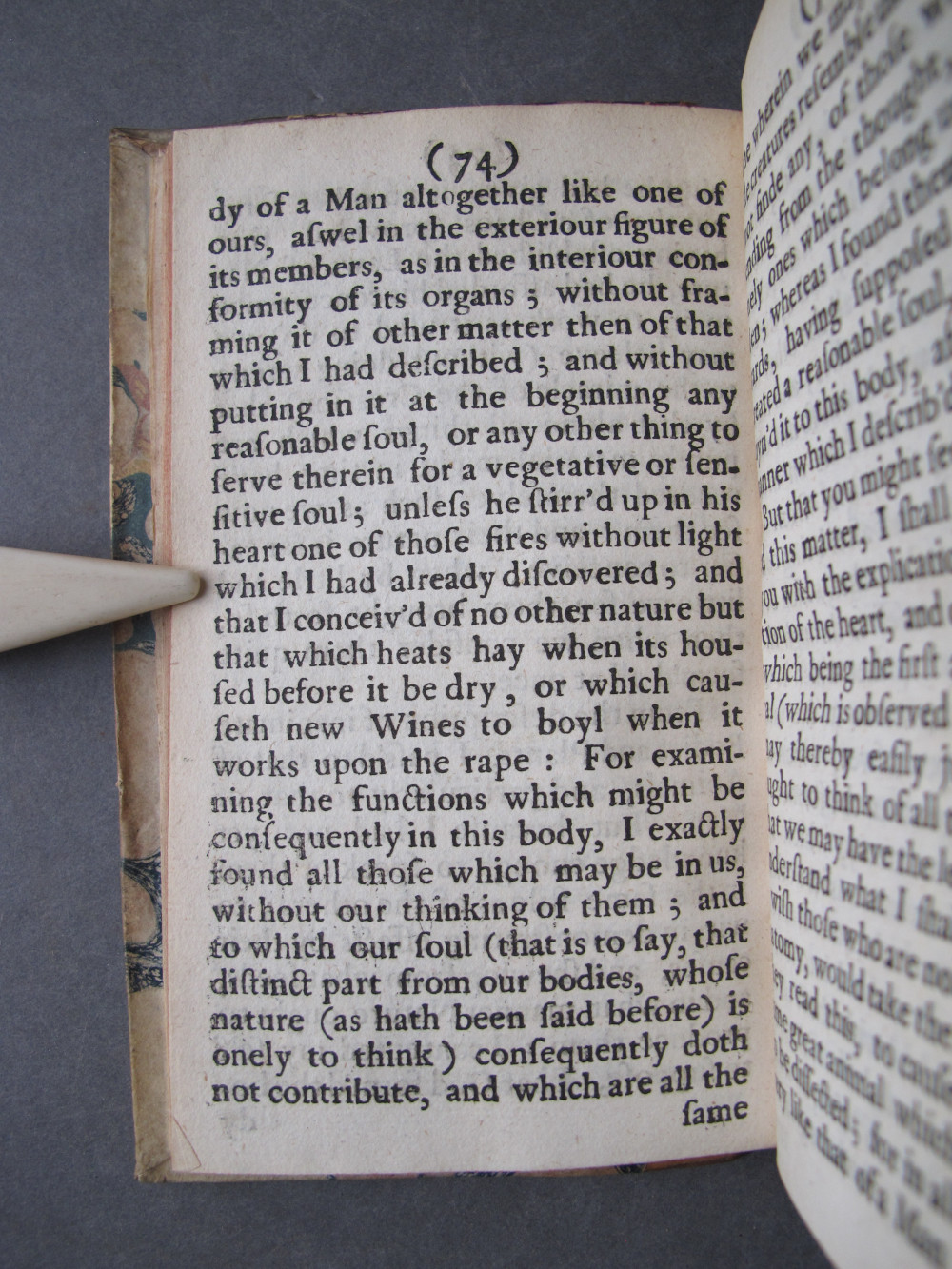

[Image 92 / 152]

(Page 74)

[Image 93 / 152]

(Page 75)

[Image 94 / 152]

(Page 76)

[Image 95 / 152]

(Page 77)

[Image 96 / 152]

(Page 78)

[Image 97 / 152]

(Page 79)

[Image 98 / 152]

(Page 80)

[Image 99 / 152]

(Page 81)

[Image 100 / 152]

(Page 82)

[Image 101 / 152]

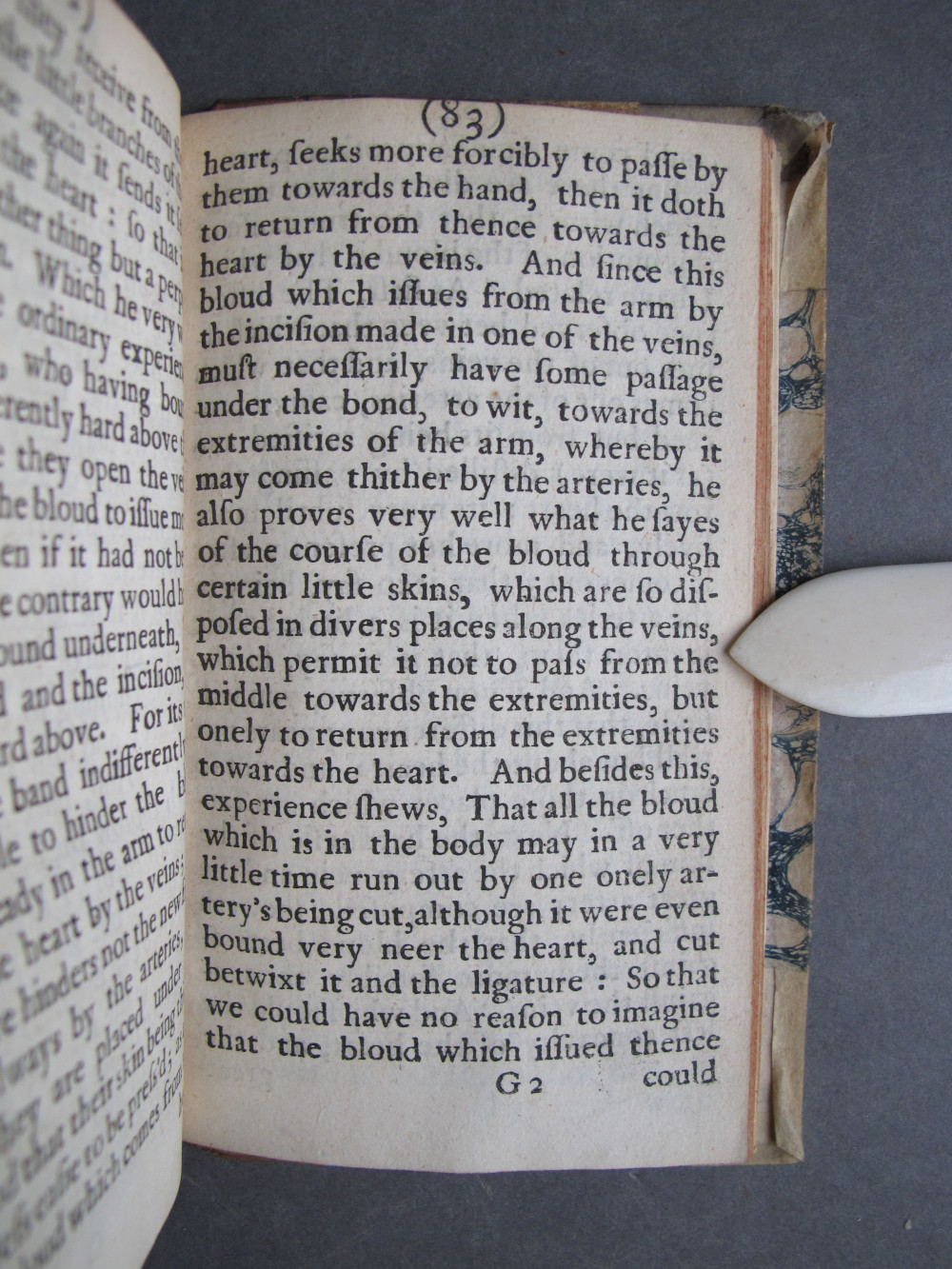

(Page 83)

[Image 102 / 152]

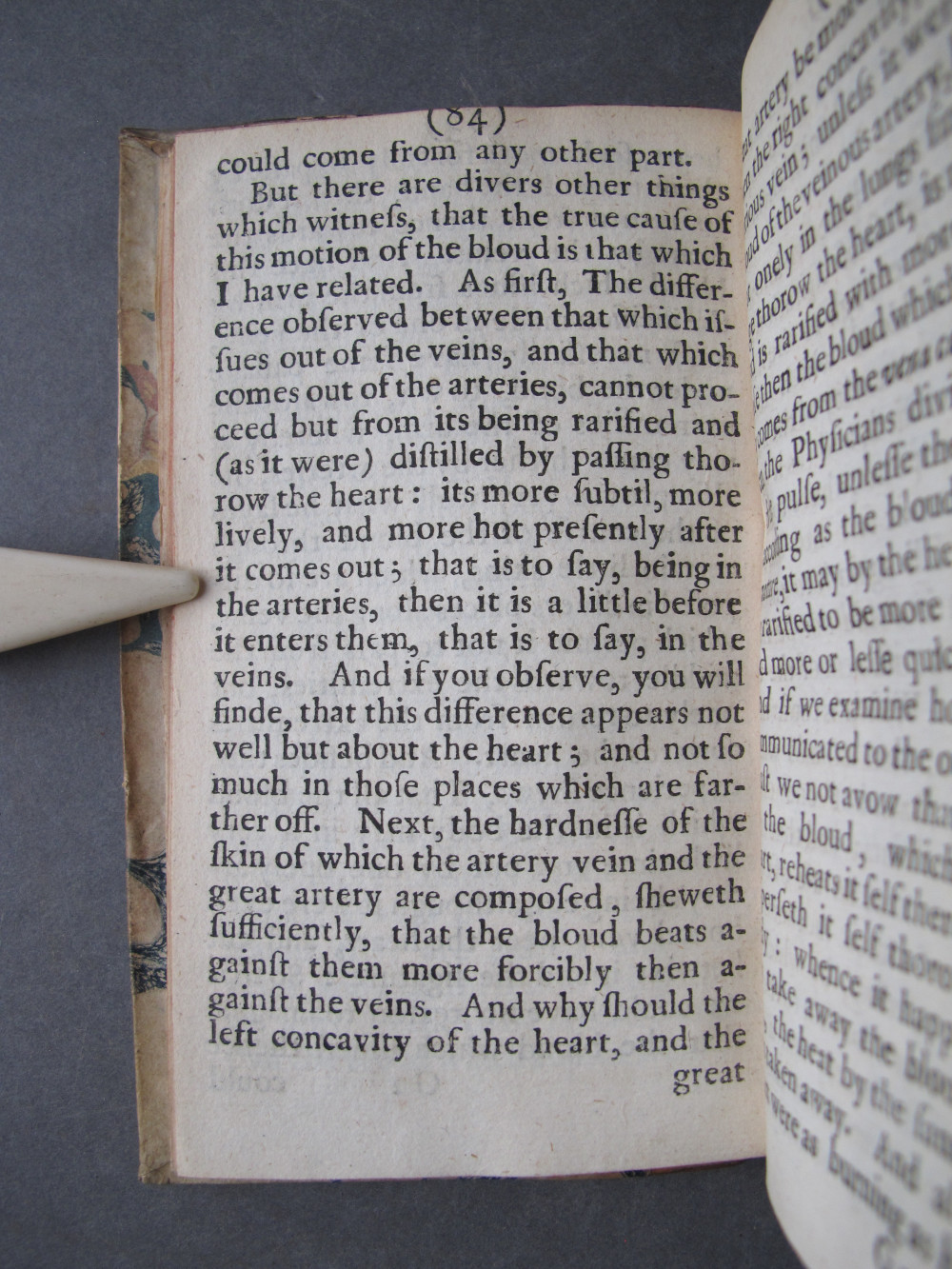

(Page 84)

[Image 103 / 152]

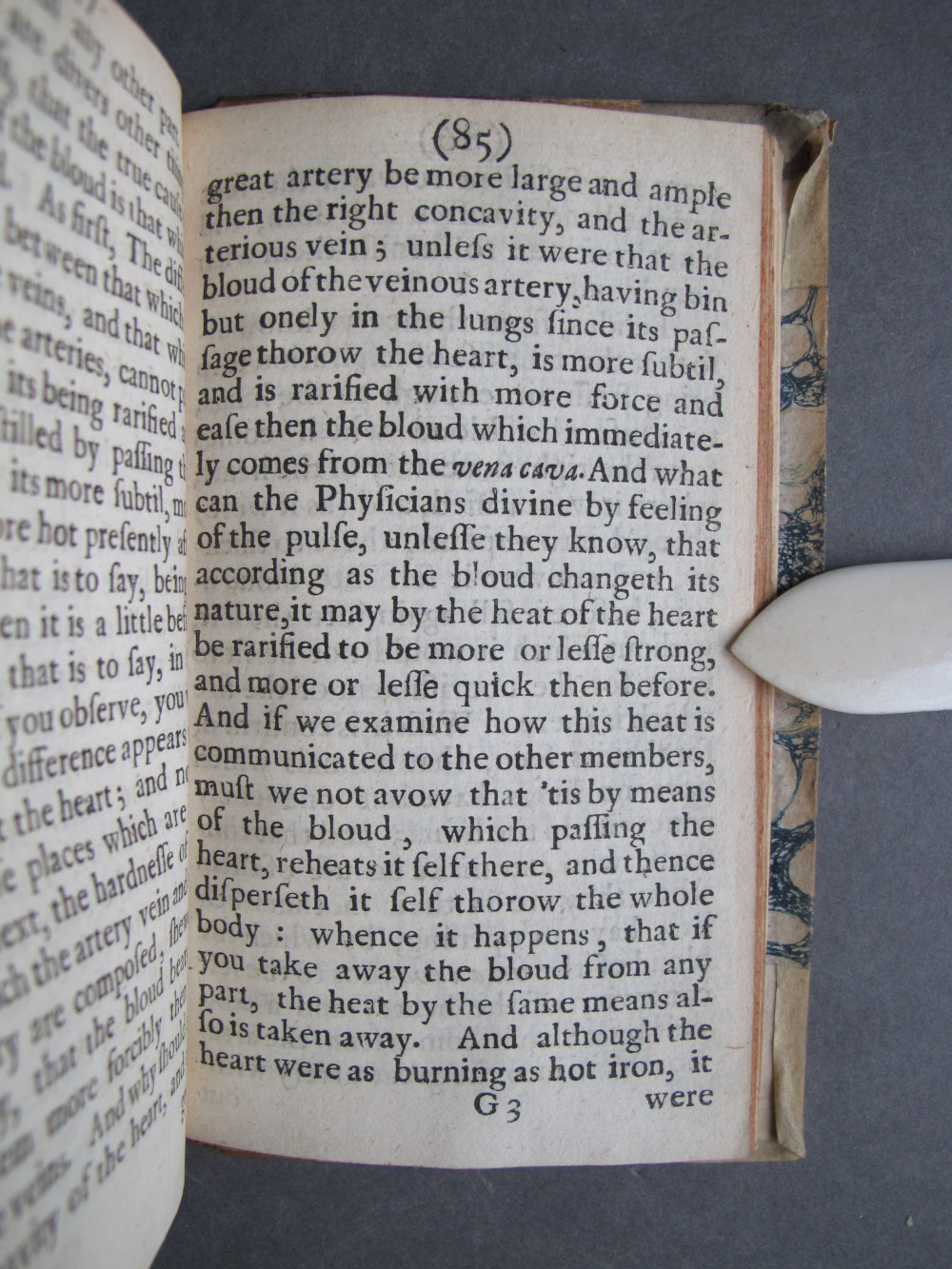

(Page 85)

[Image 104 / 152]

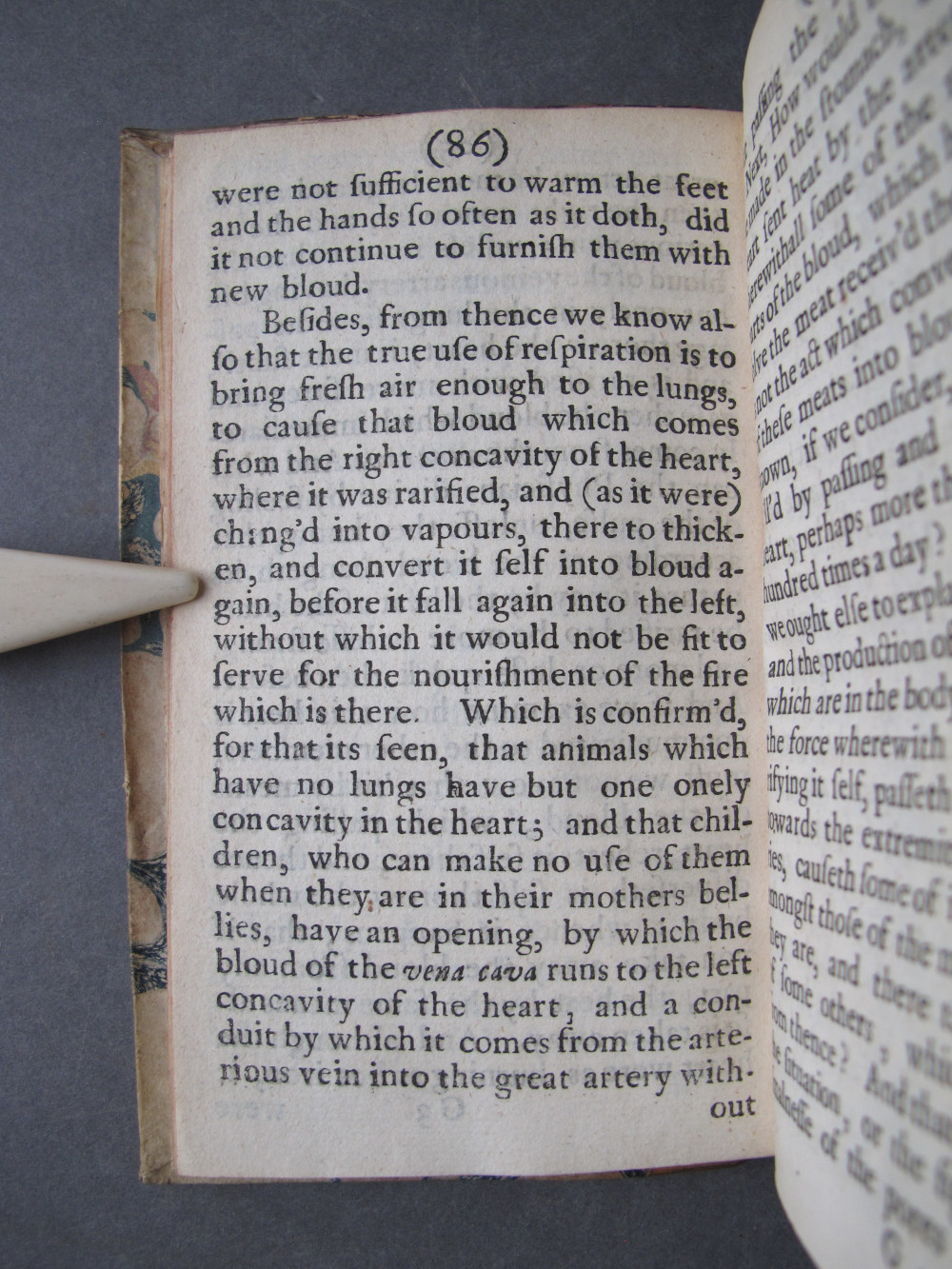

(Page 86)

[Image 105 / 152]

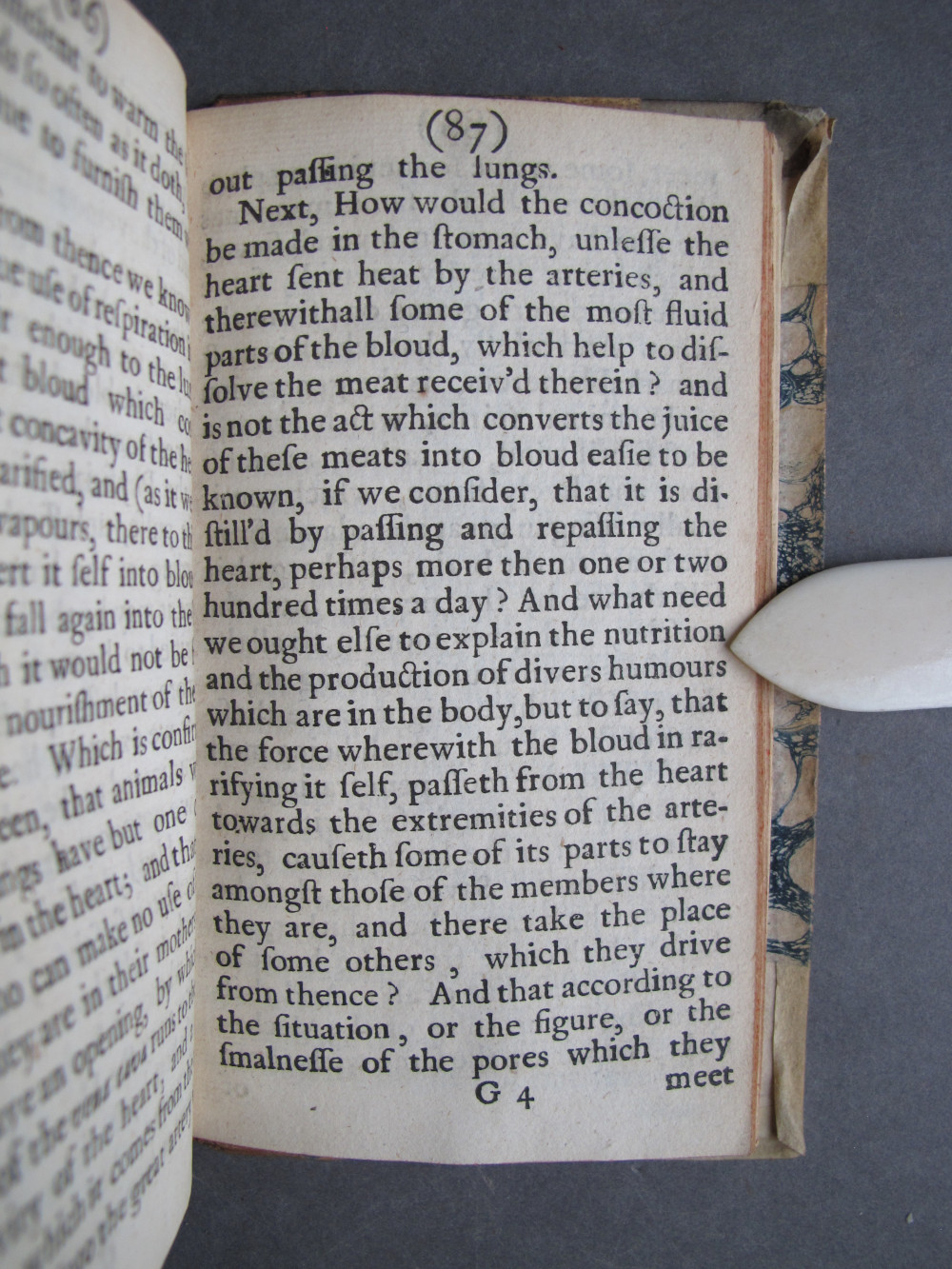

(Page 87)

[Image 106 / 152]

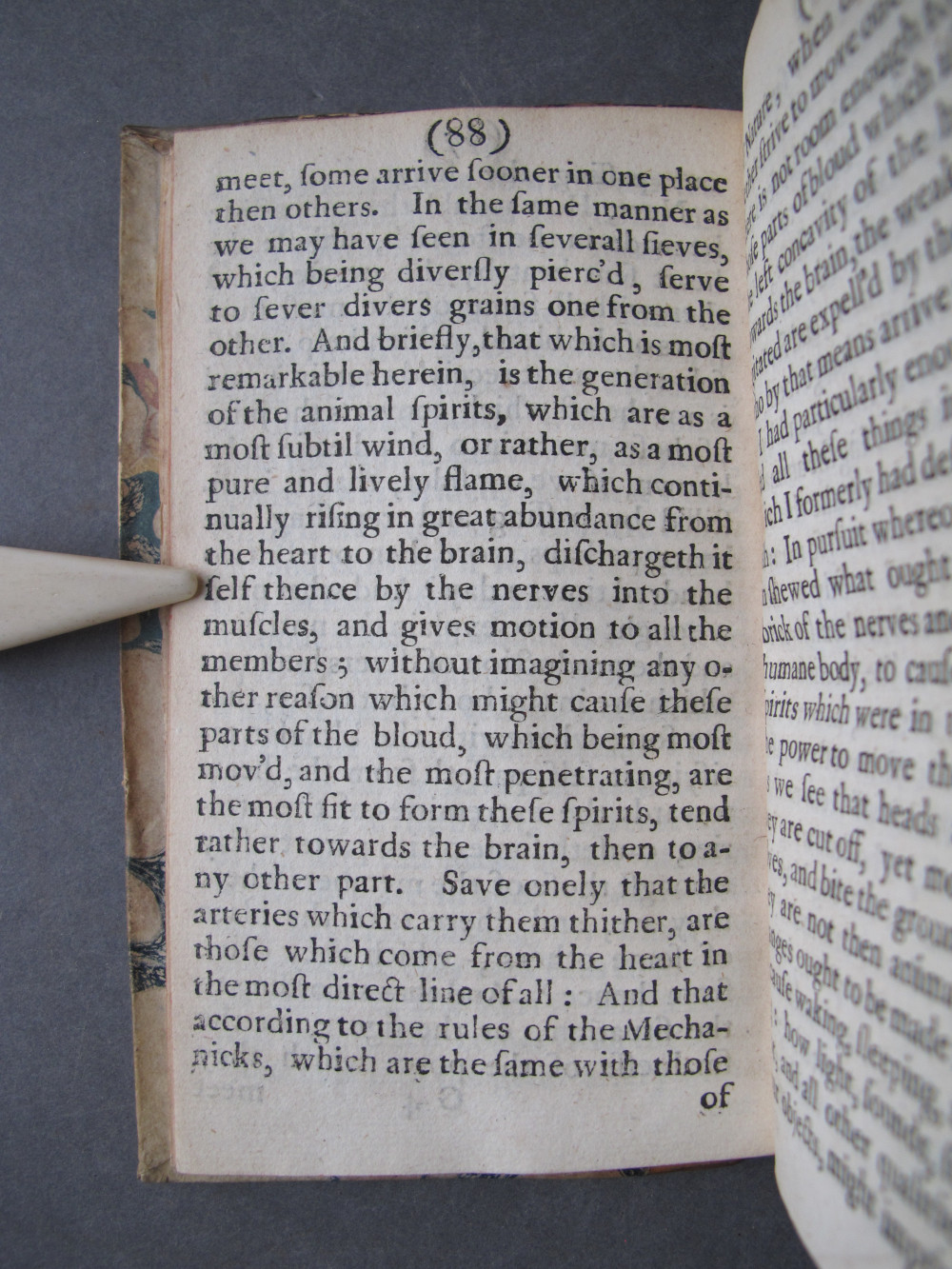

(Page 88)

[Image 107 / 152]

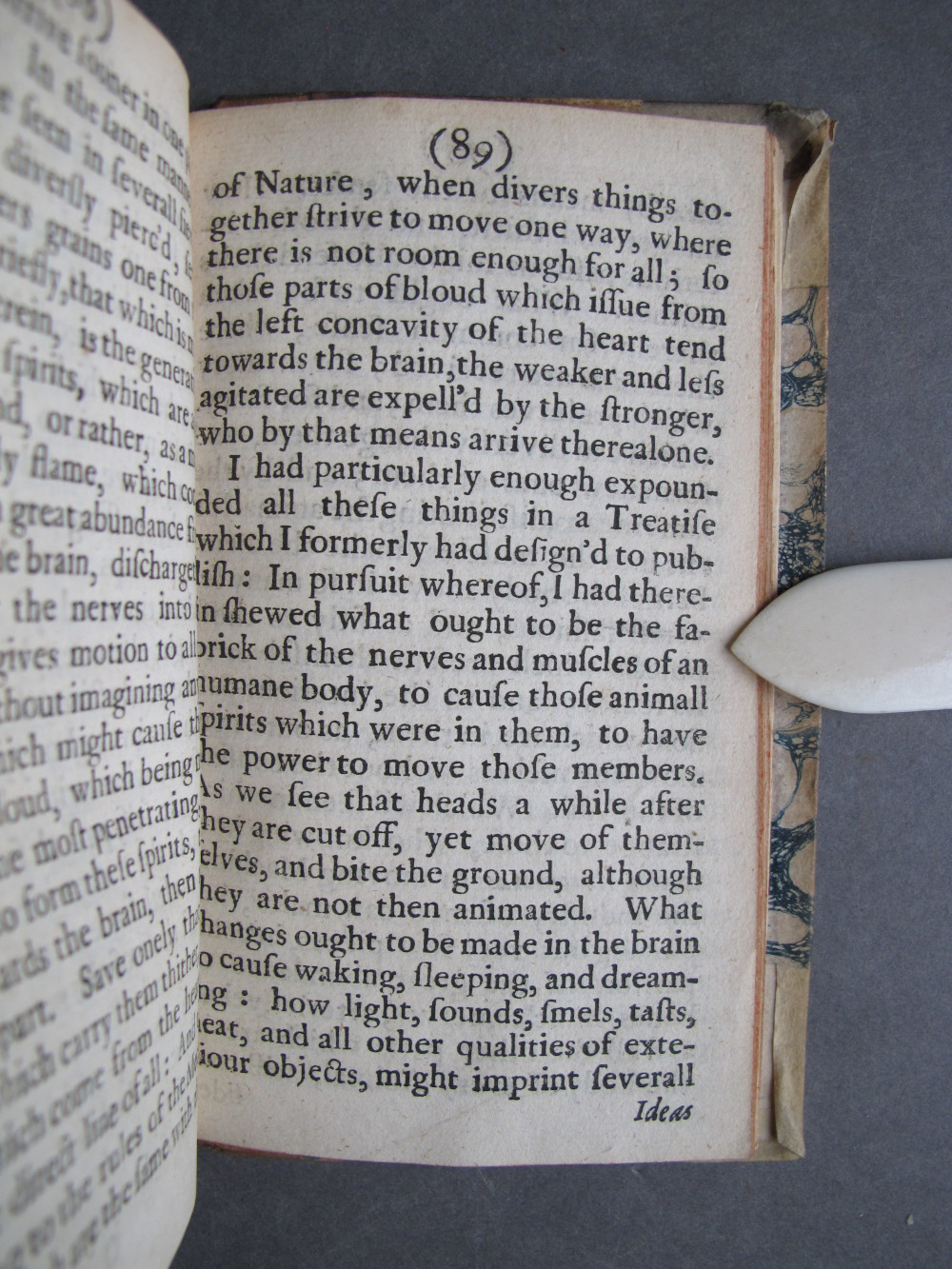

(Page 89)

[Image 108 / 152]

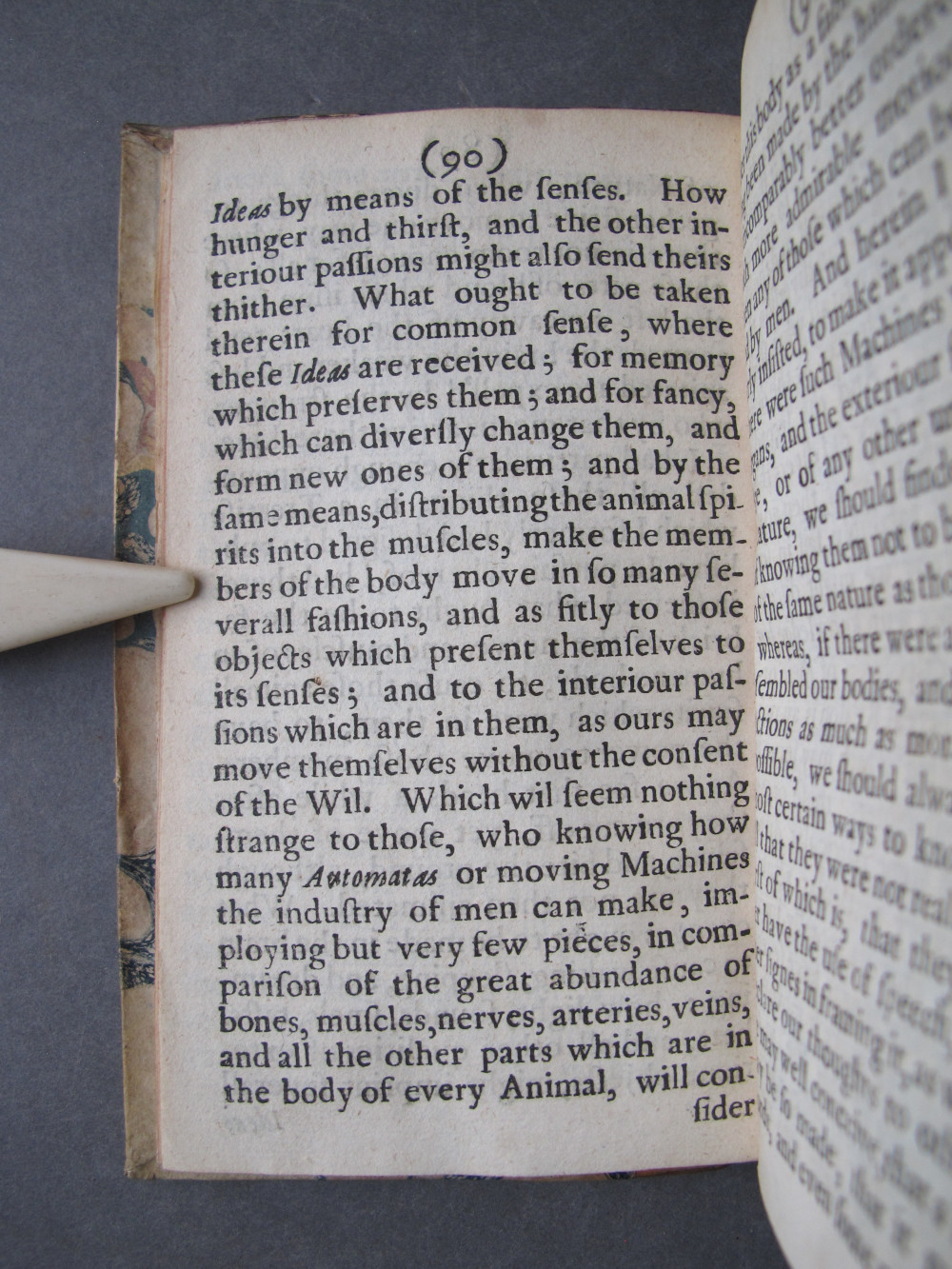

(Page 90)

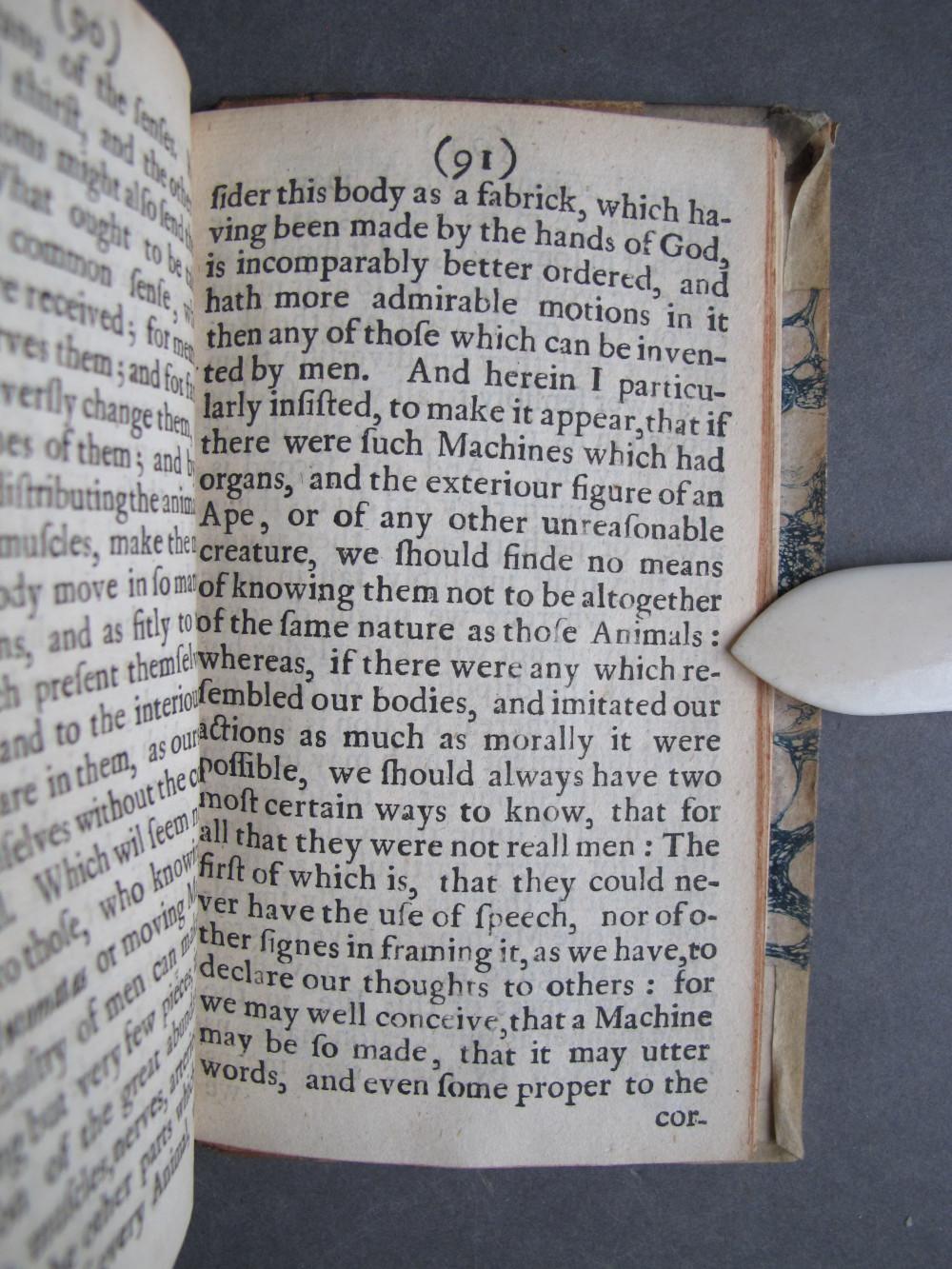

[Image 109 / 152]

(Page 91)

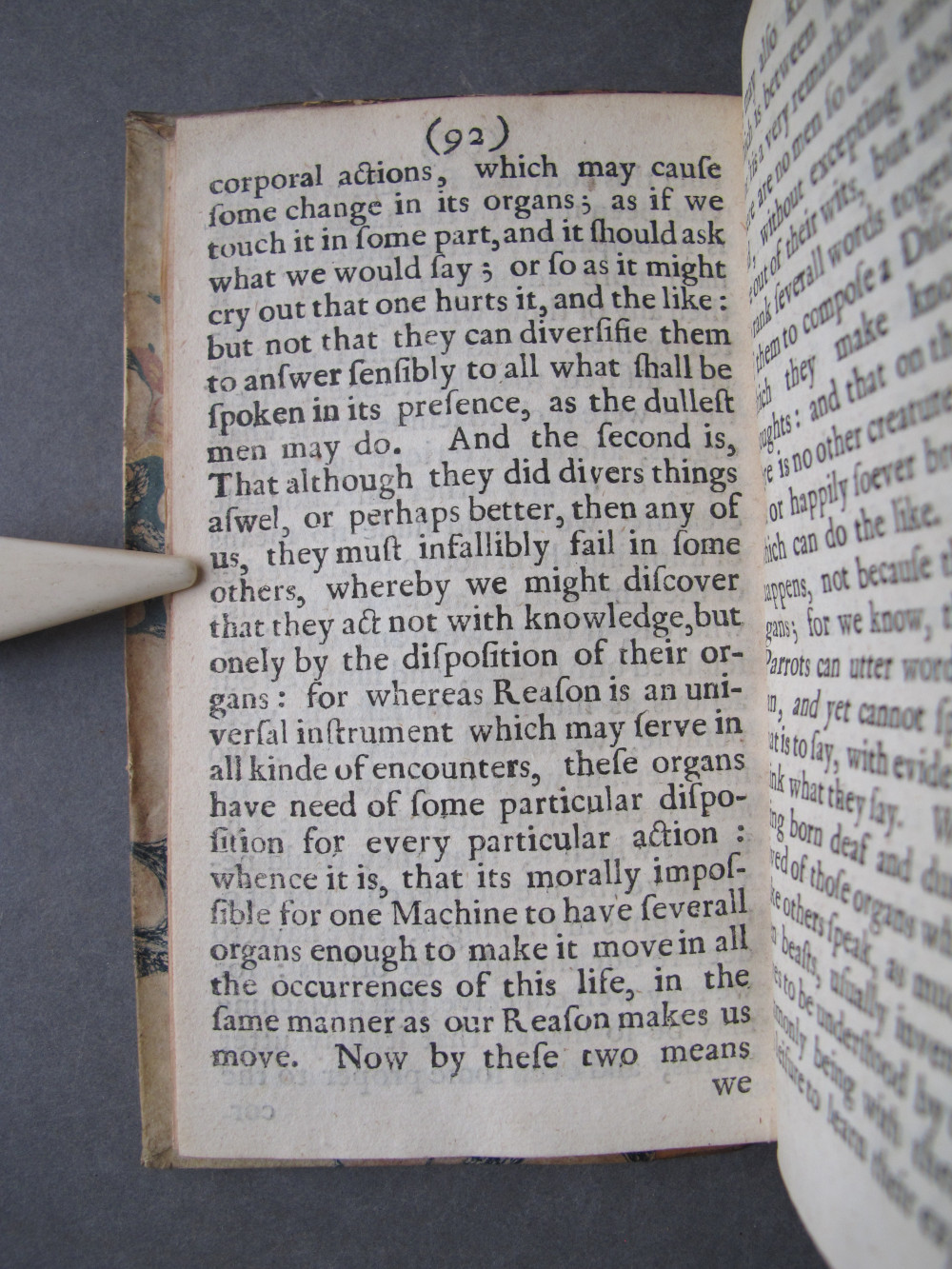

[Image 110 / 152]

(Page 92)

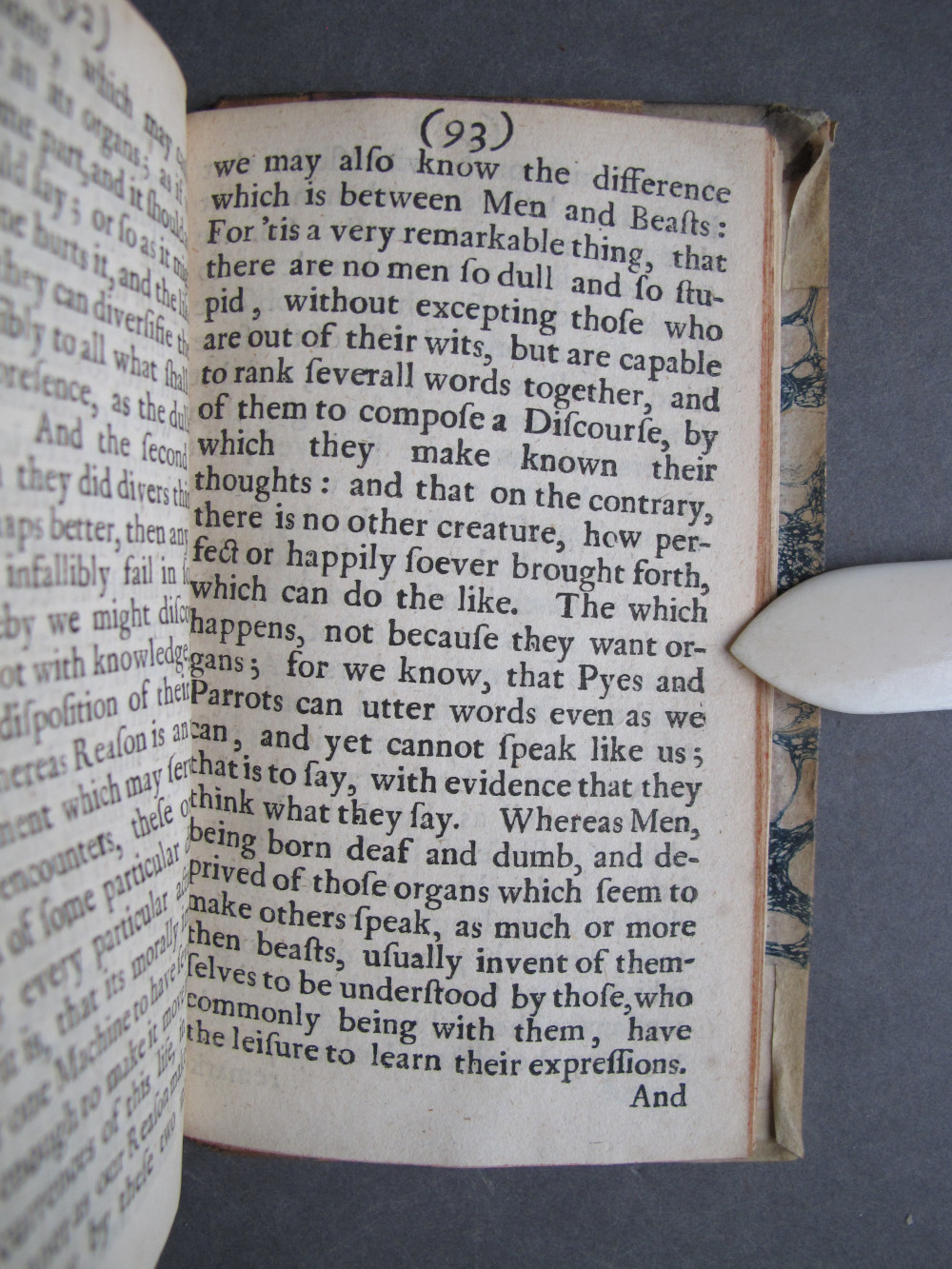

[Image 111 / 152]

(Page 93)

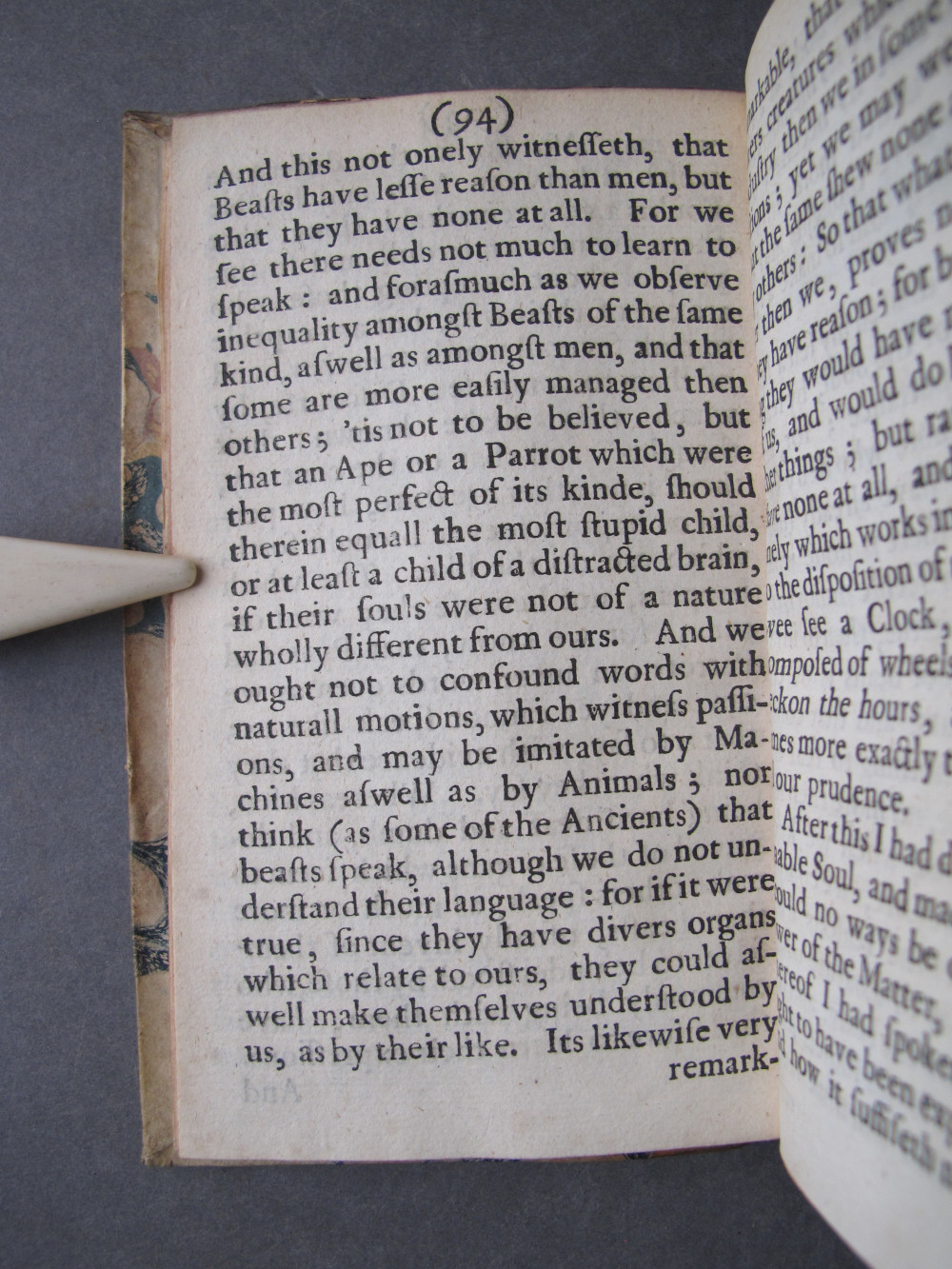

[Image 112 / 152]

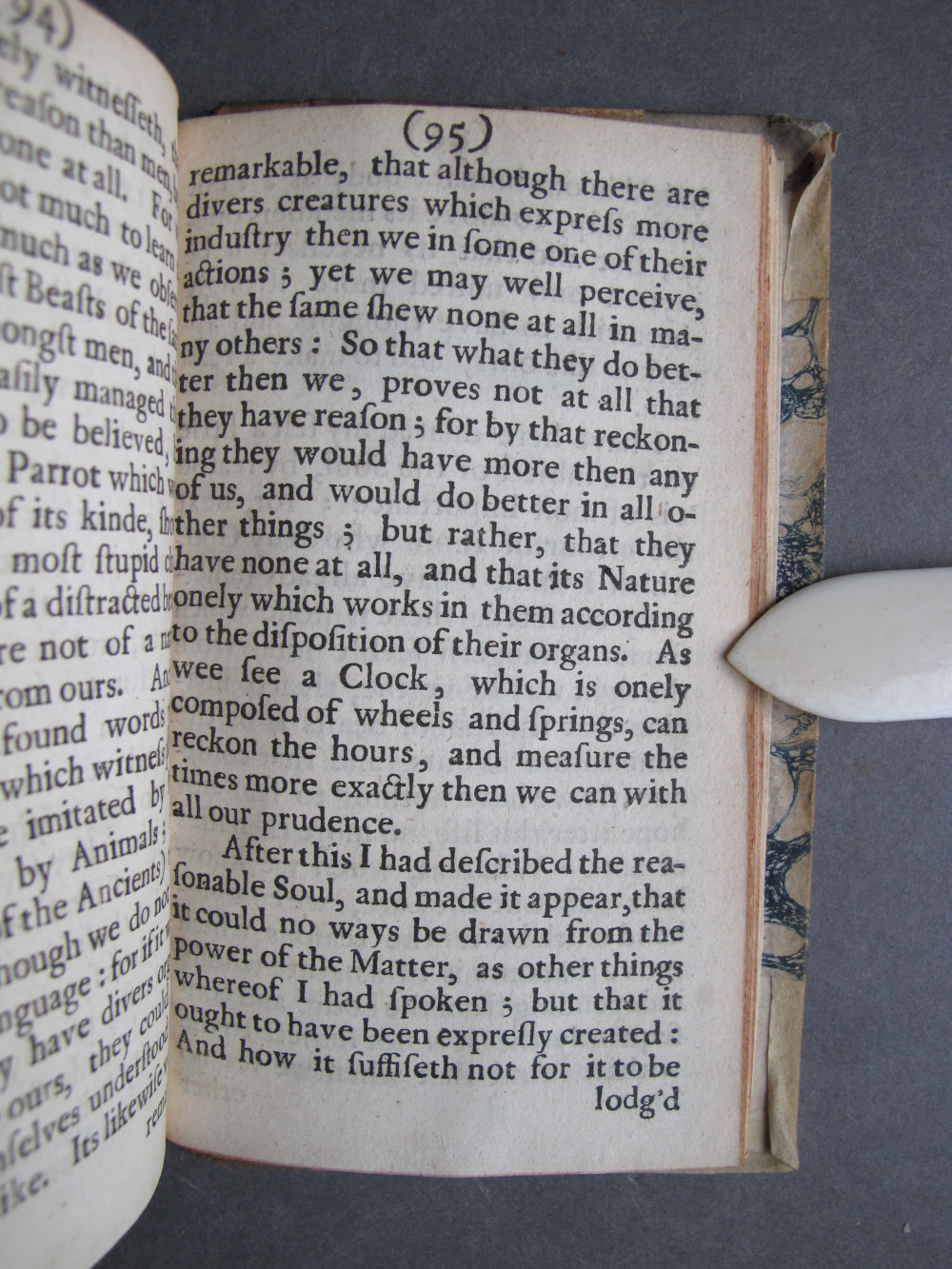

(Page 94)

[Image 113 / 152]

(Page 95)

[Image 114 / 152]

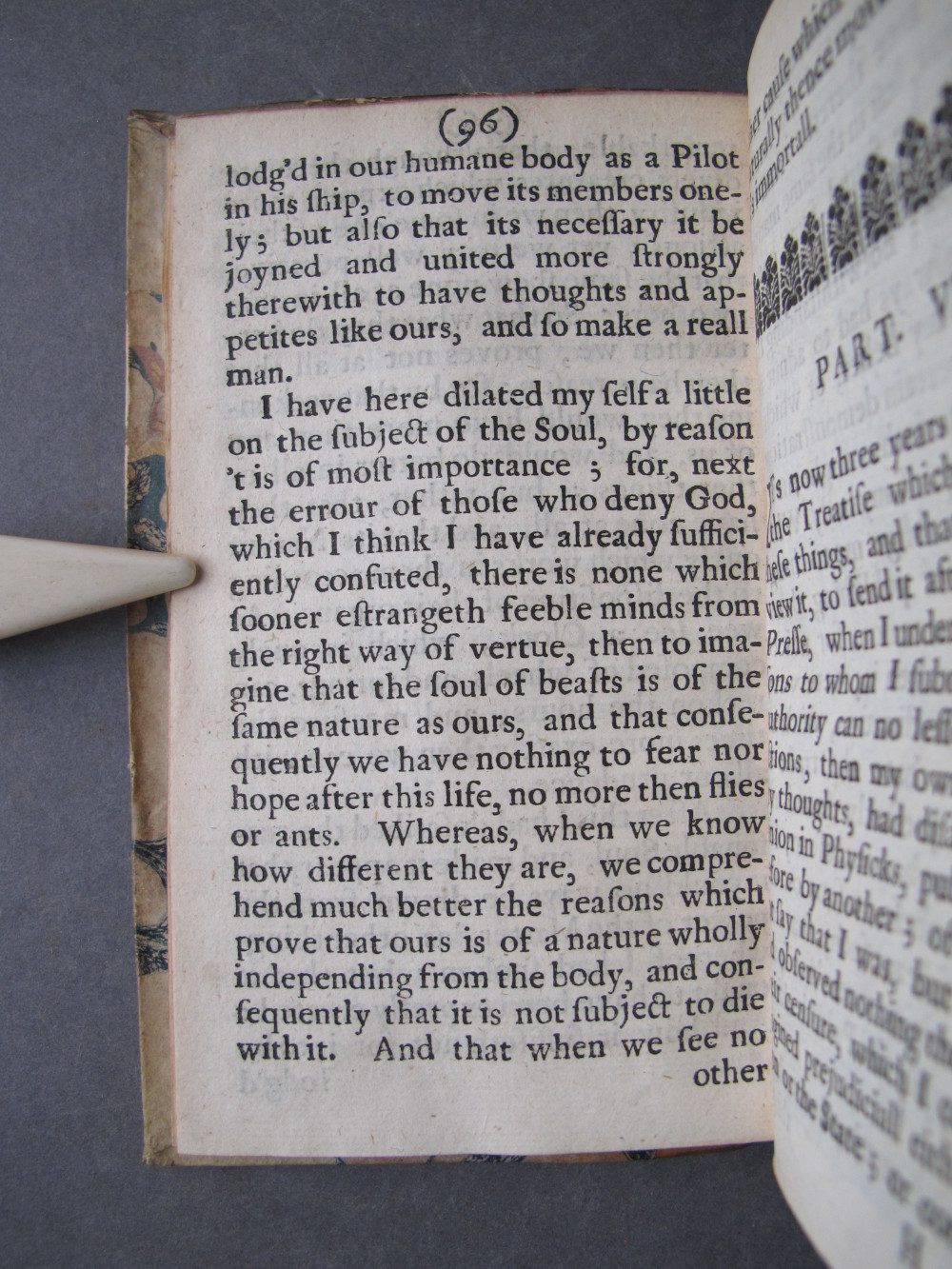

(Page 96)

[Image 115 / 152]

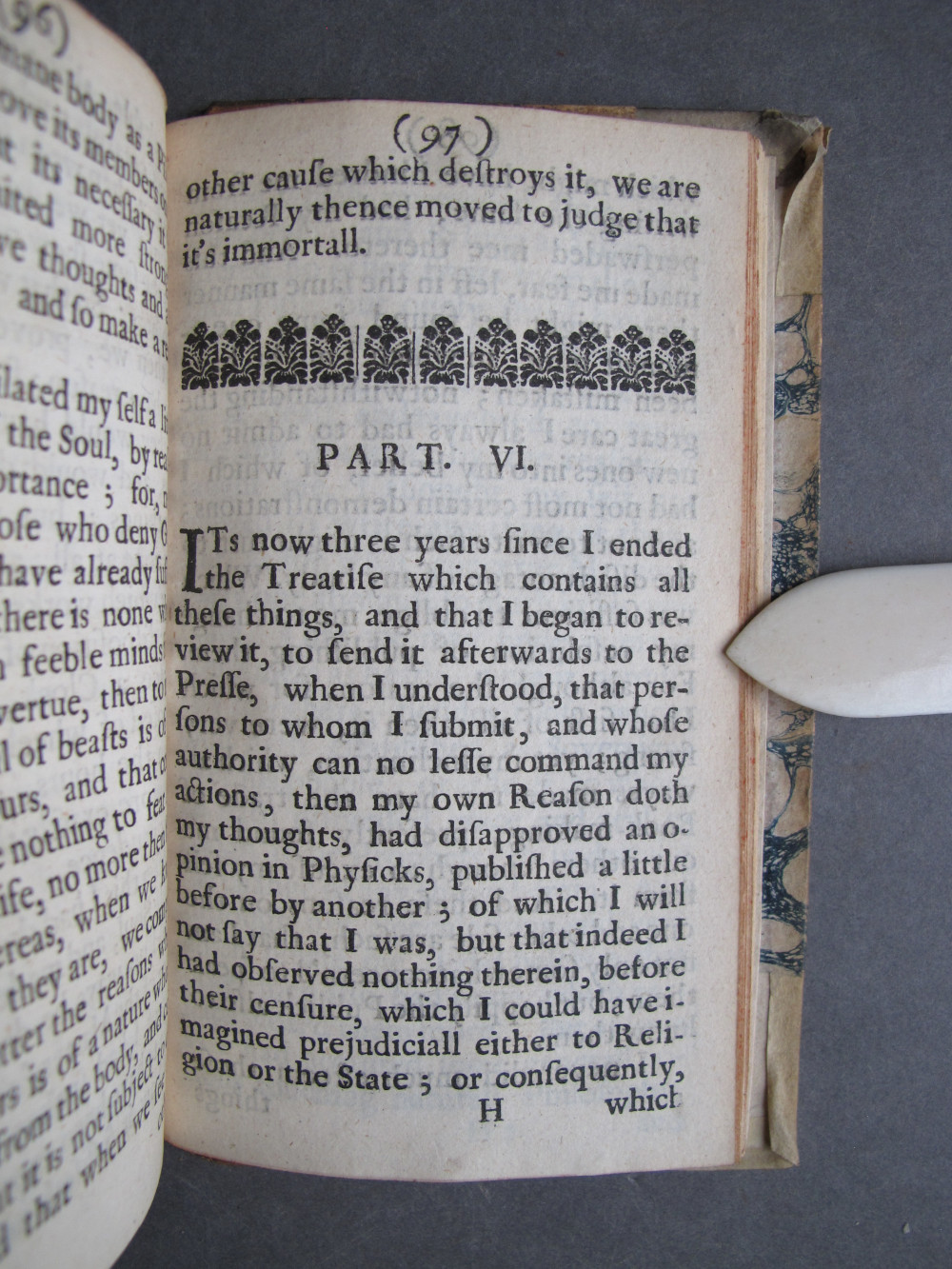

(Page 97)

[Image 116 / 152]

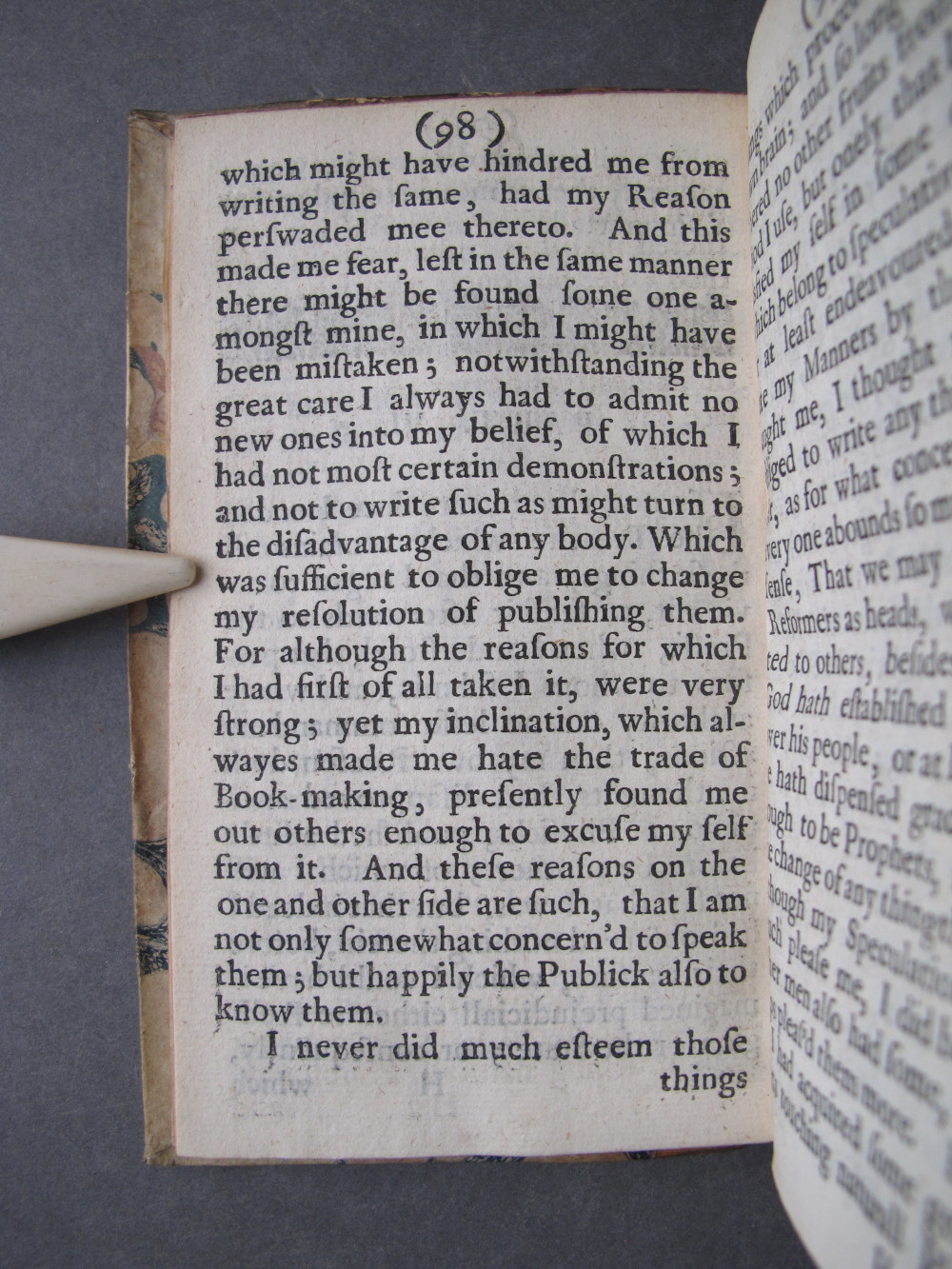

(Page 98)

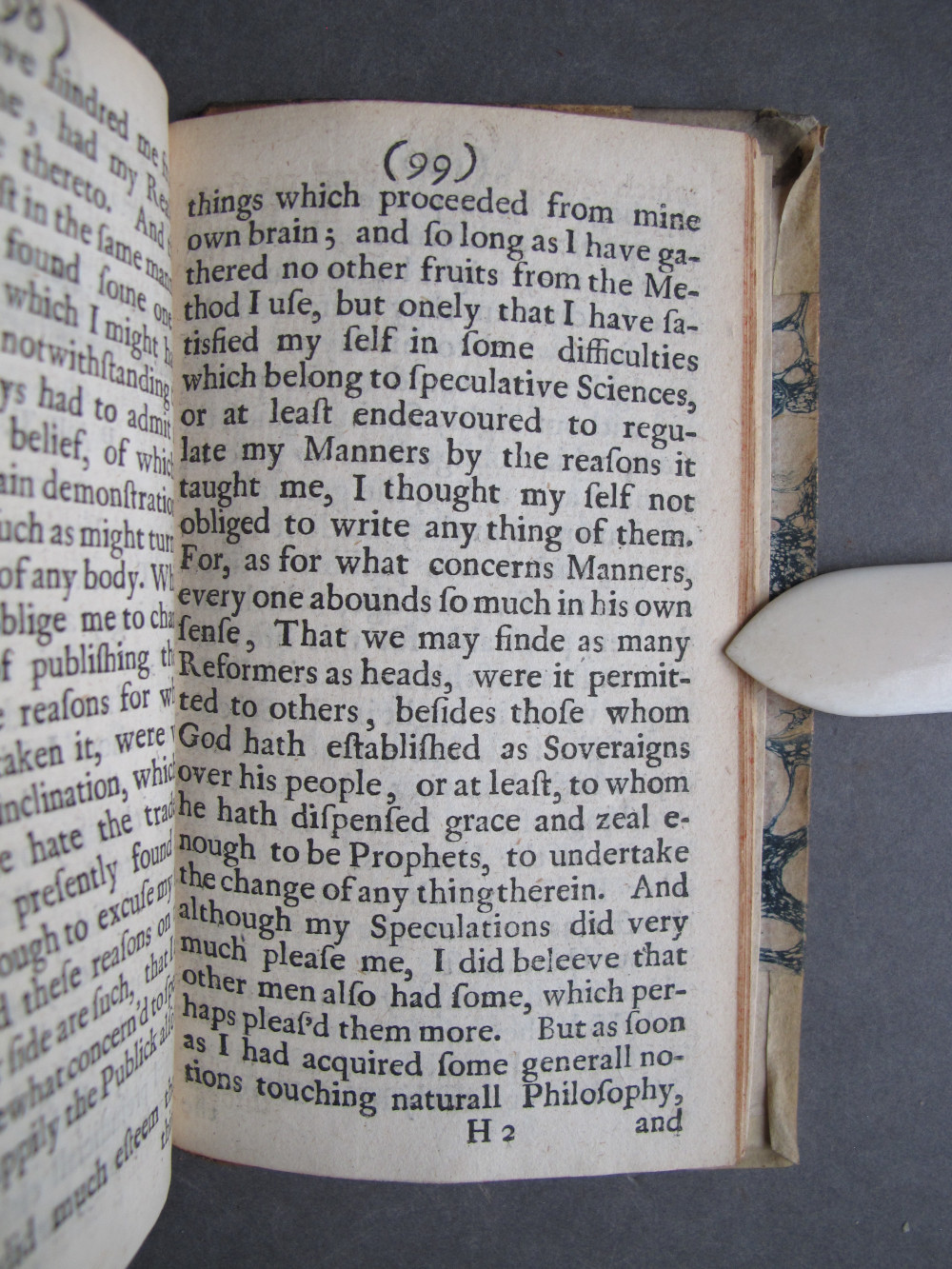

[Image 117 / 152]

(Page 99)

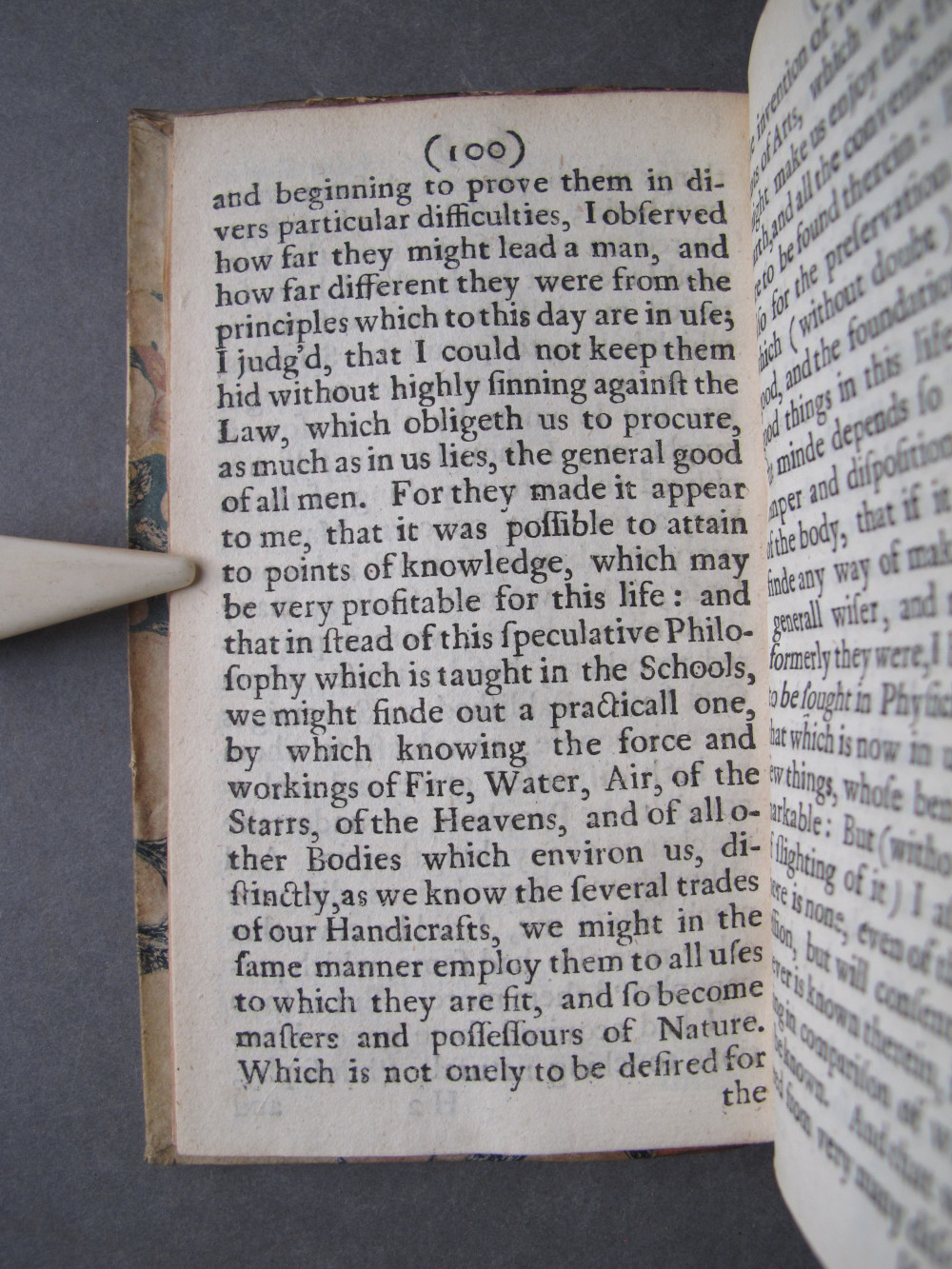

[Image 118 / 152]

(Page 100)

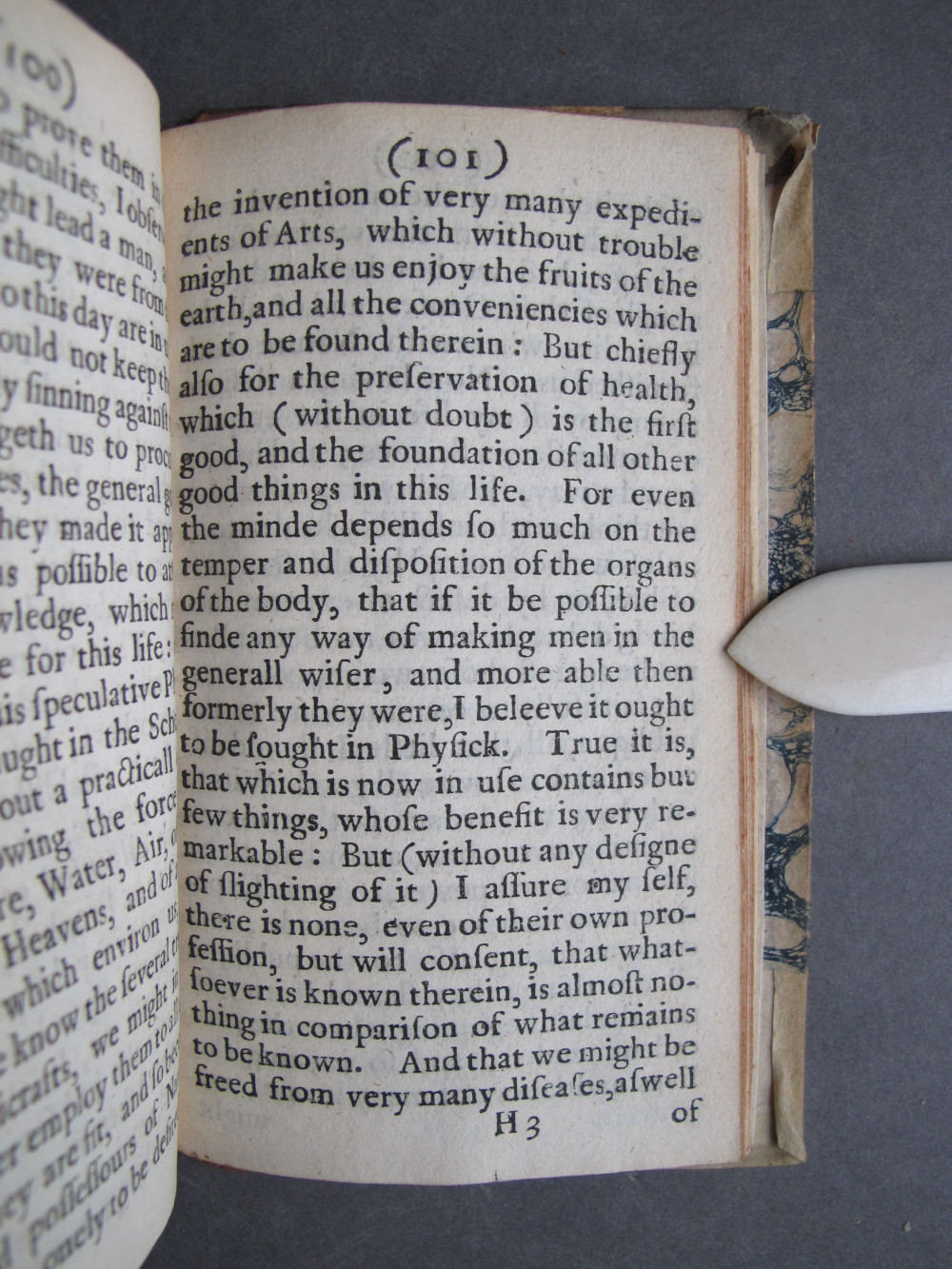

[Image 119 / 152]

(Page 101)

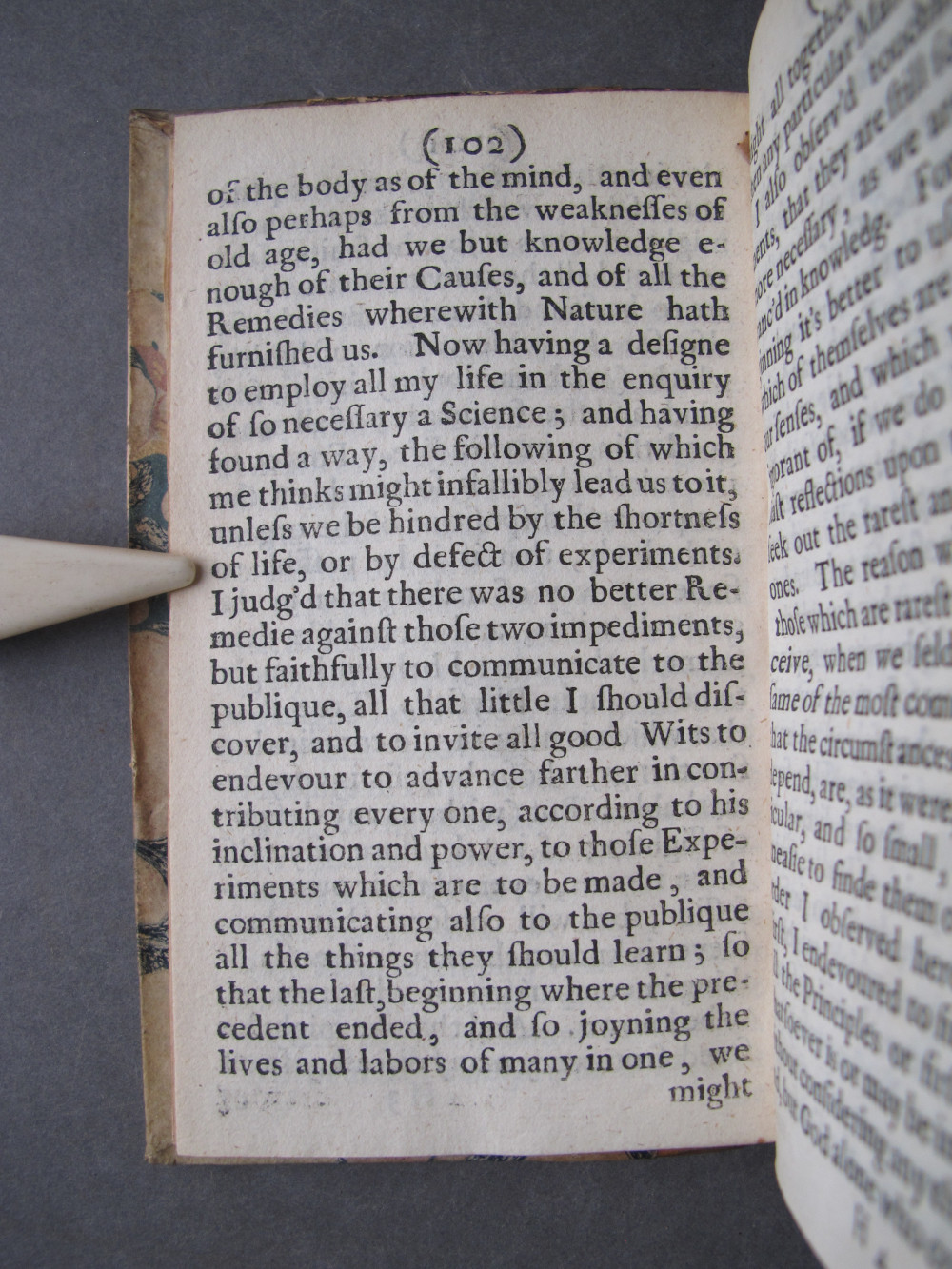

[Image 120 / 152]

(Page 102)

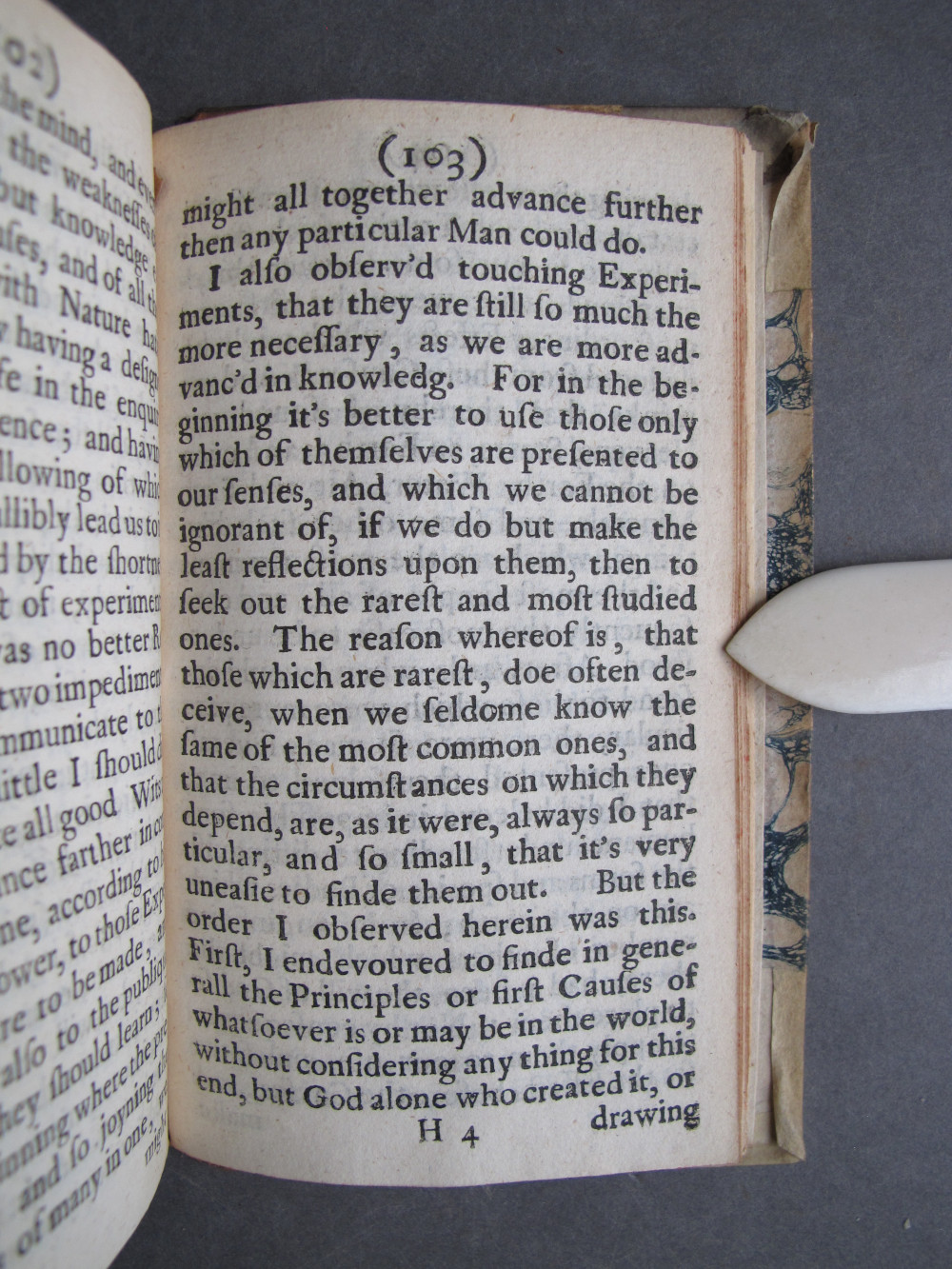

[Image 121 / 152]

(Page 103)

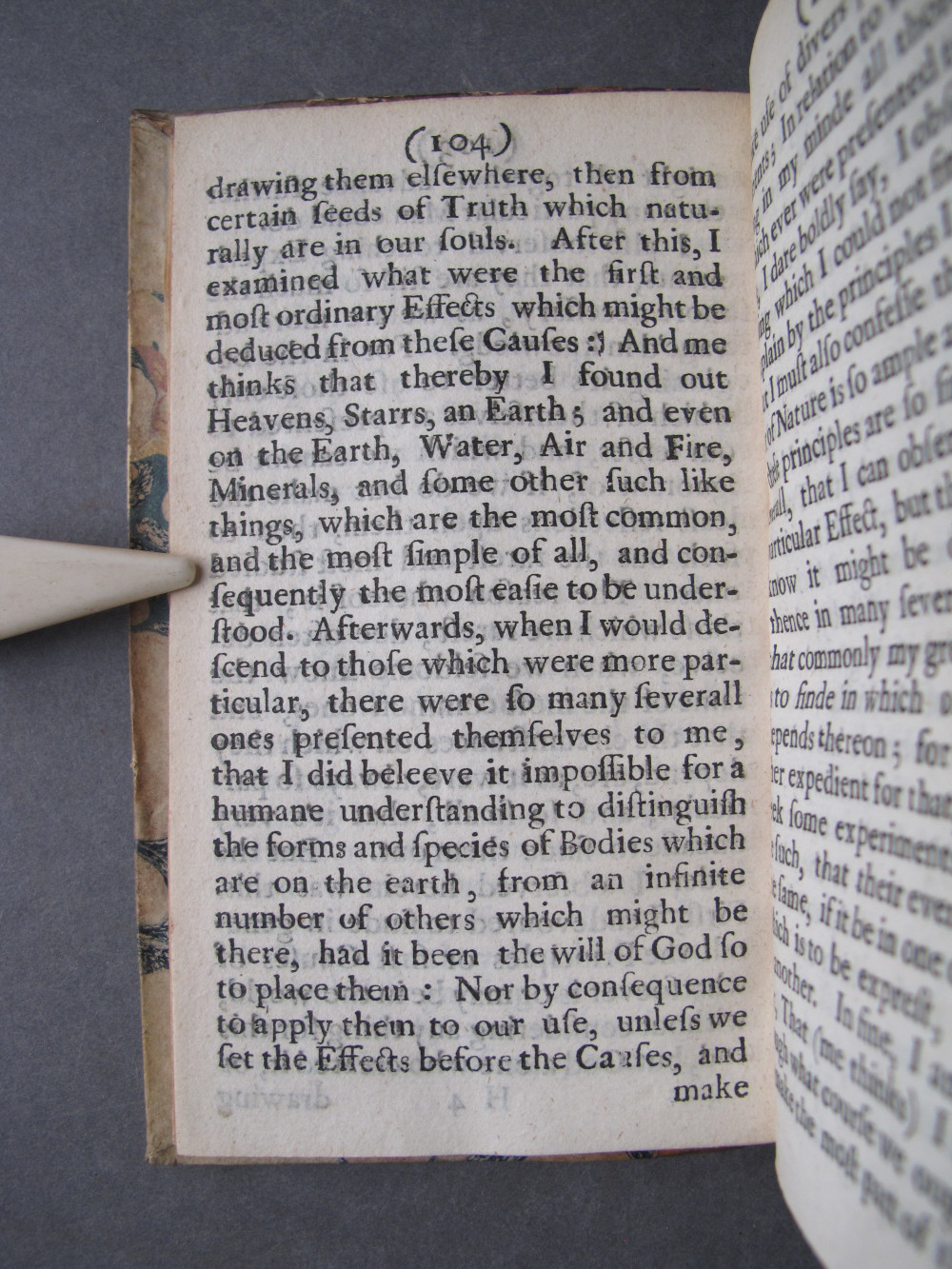

[Image 122 / 152]

(Page 104)

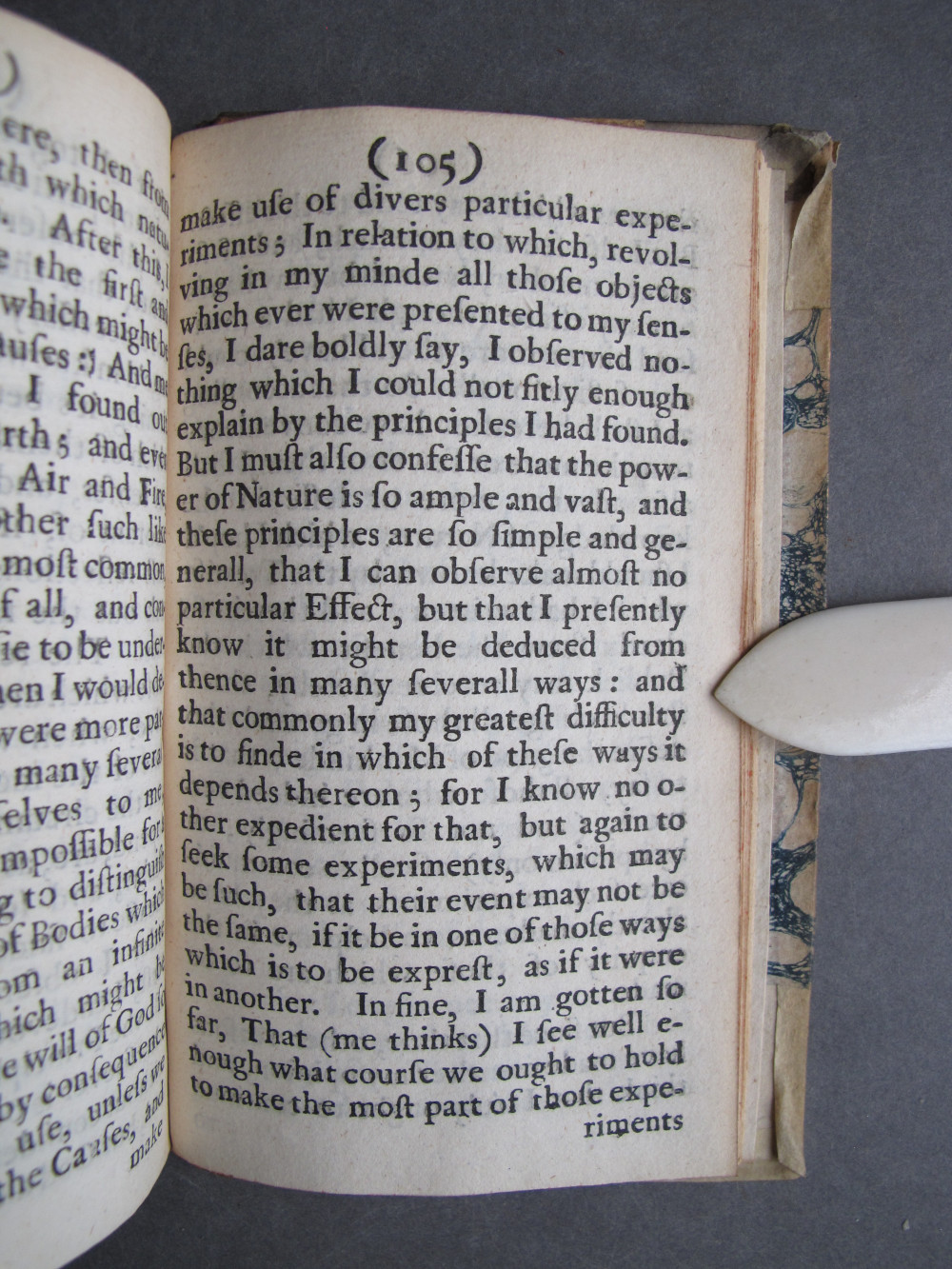

[Image 123 / 152]

(Page 105)

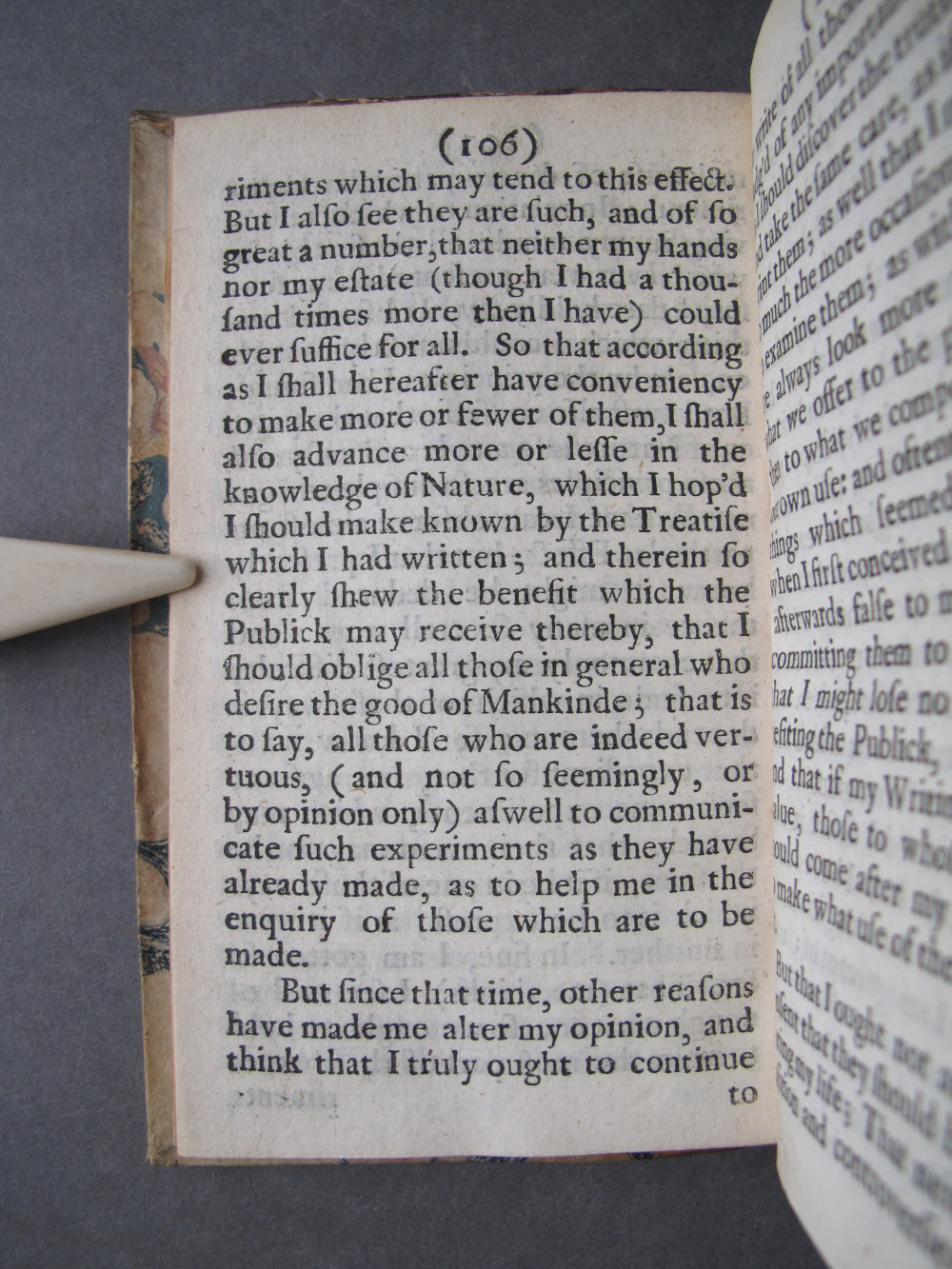

[Image 124 / 152]

(Page 106)

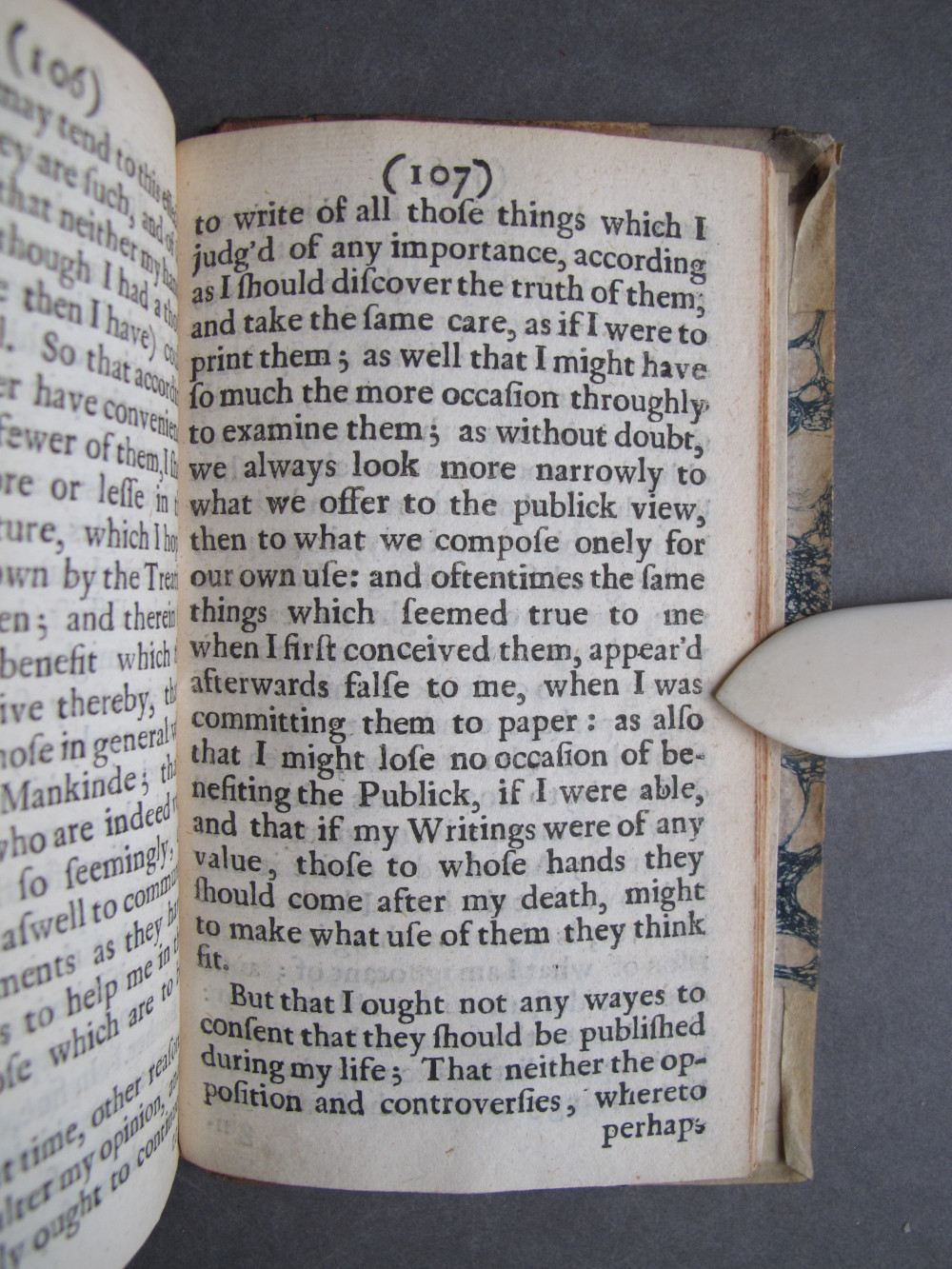

[Image 125 / 152]

(Page 107)

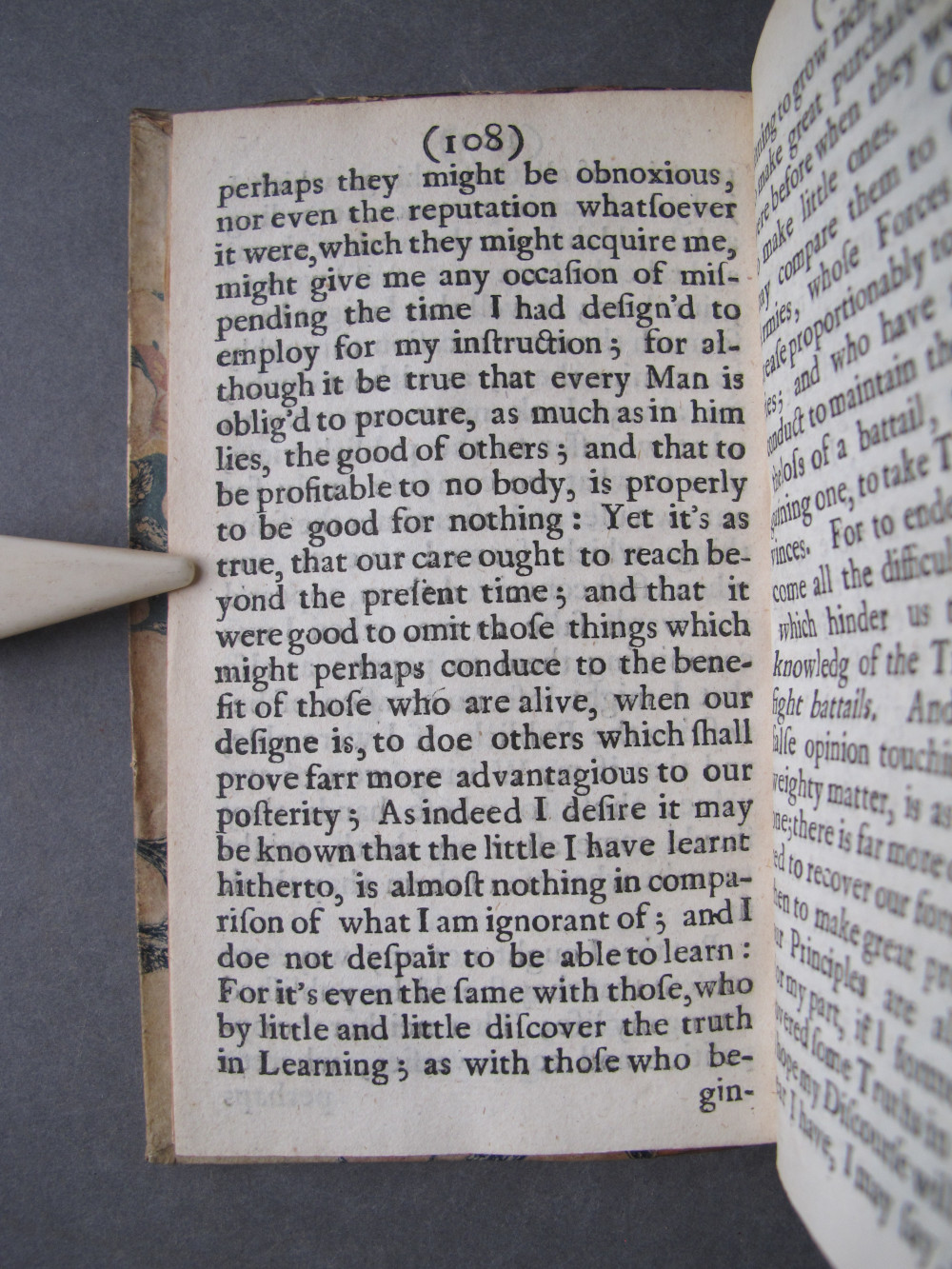

[Image 126 / 152]

(Page 108)

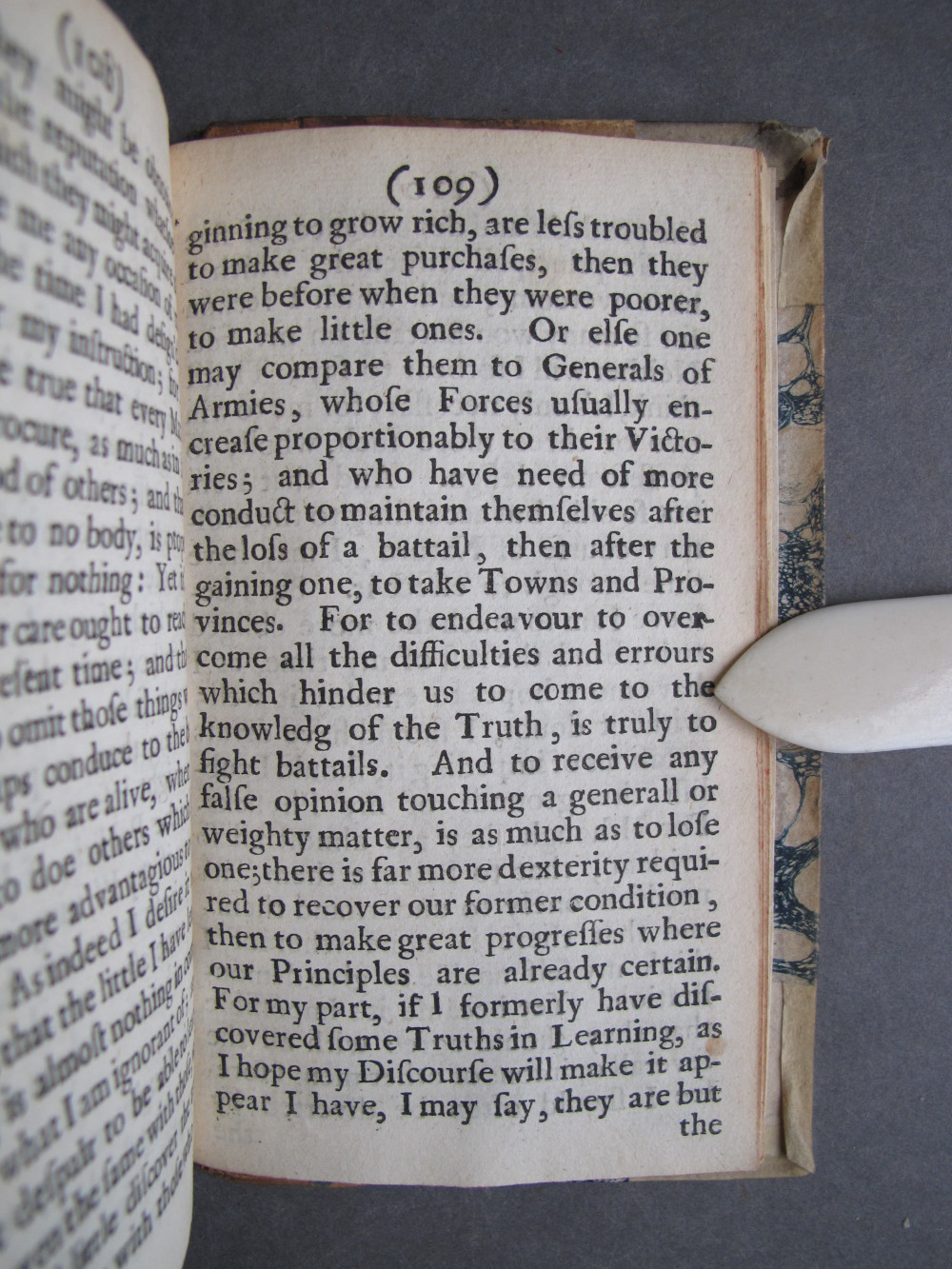

[Image 127 / 152]

(Page 109)

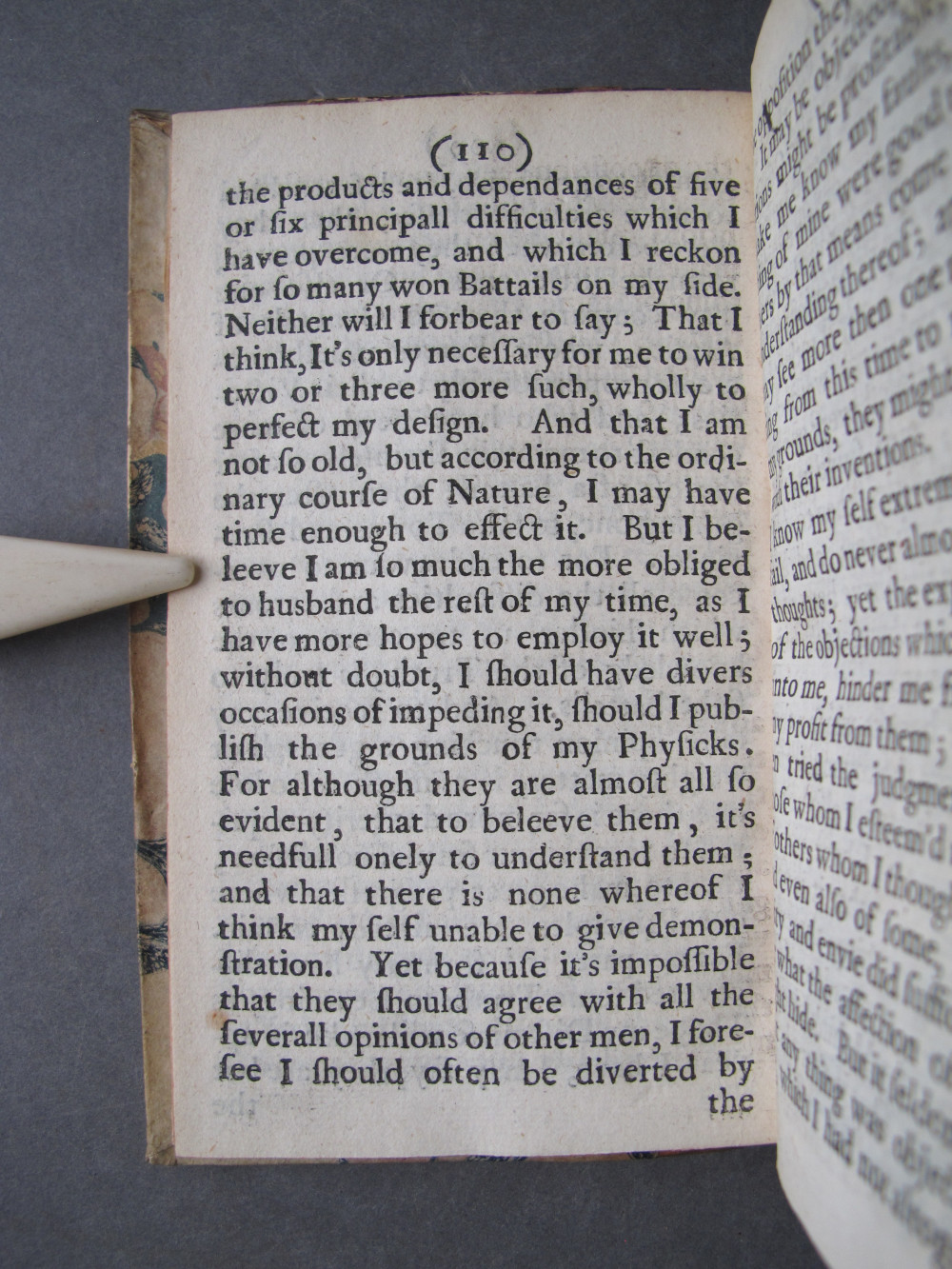

[Image 128 / 152]

(Page 110)

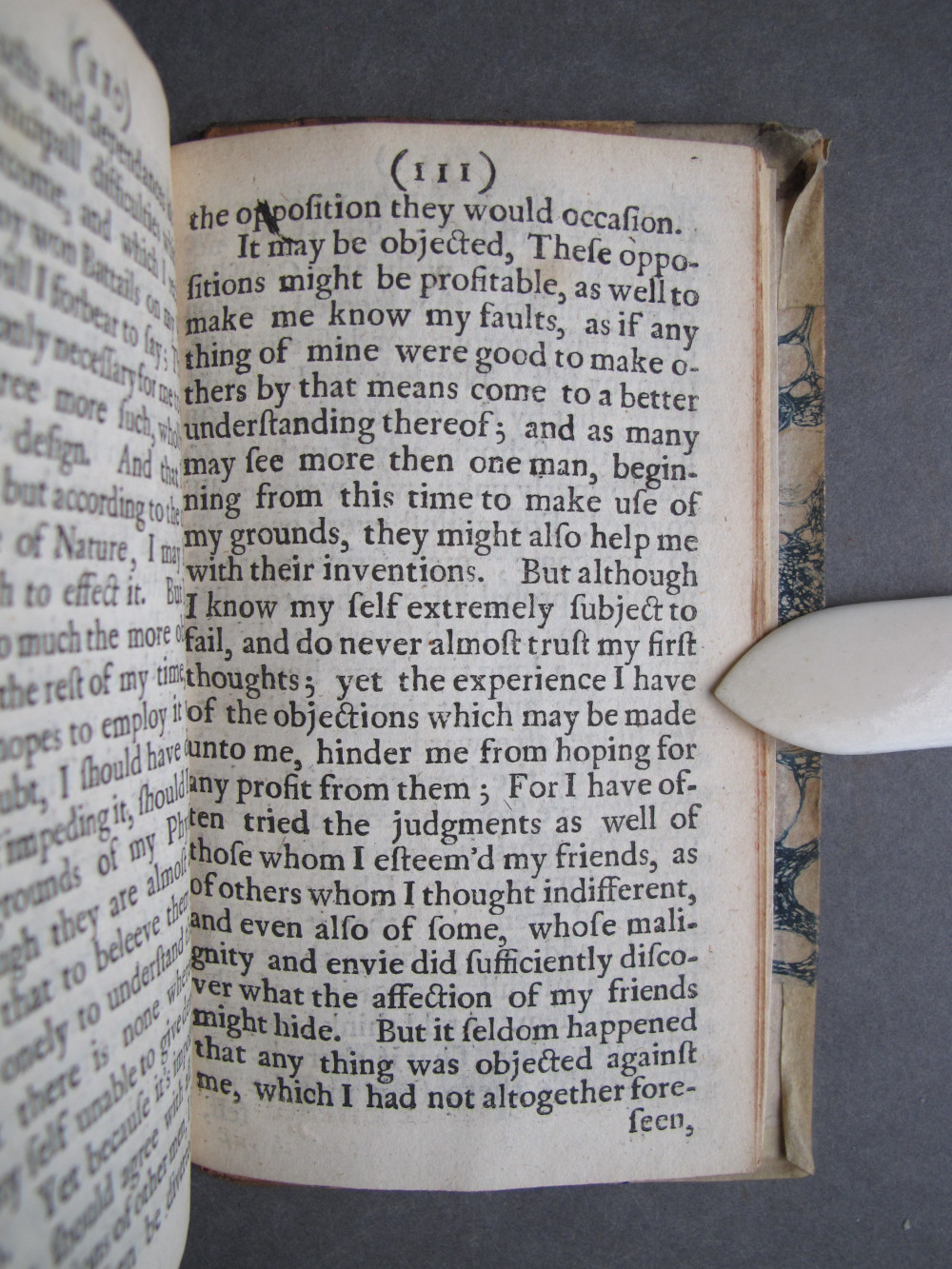

[Image 129 / 152]

(Page 111)

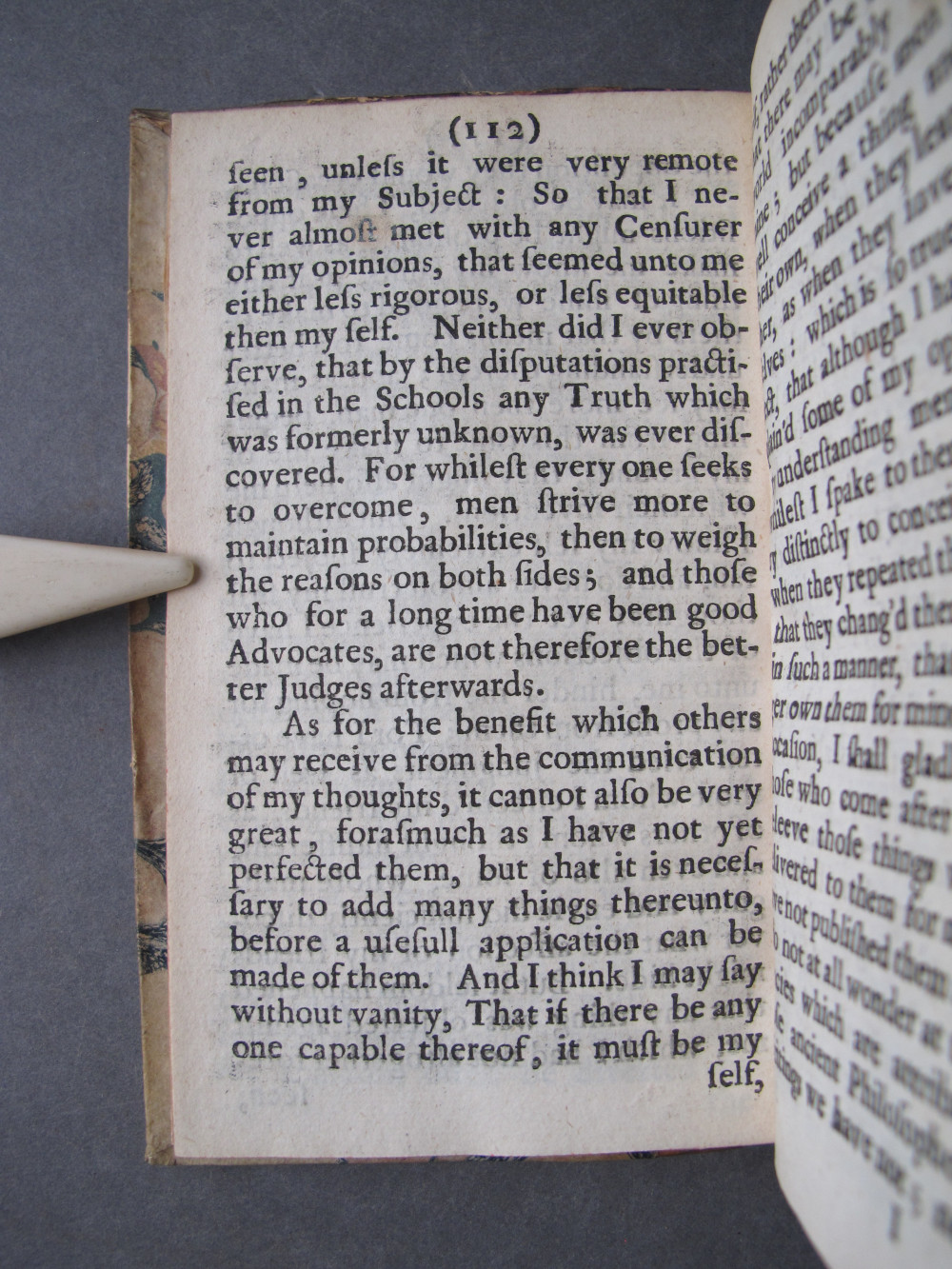

[Image 130 / 152]

(Page 112)

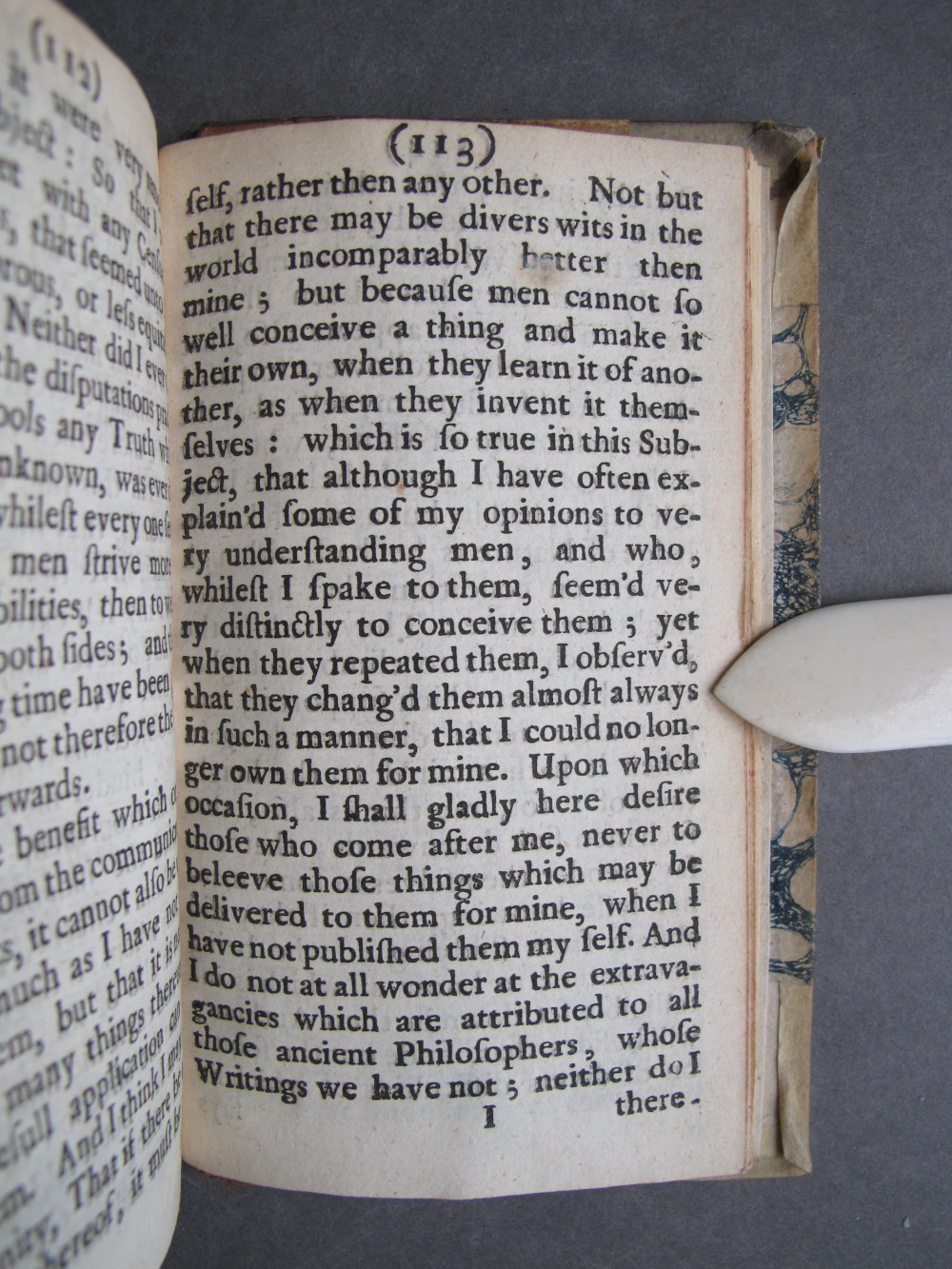

[Image 131 / 152]

(Page 113)

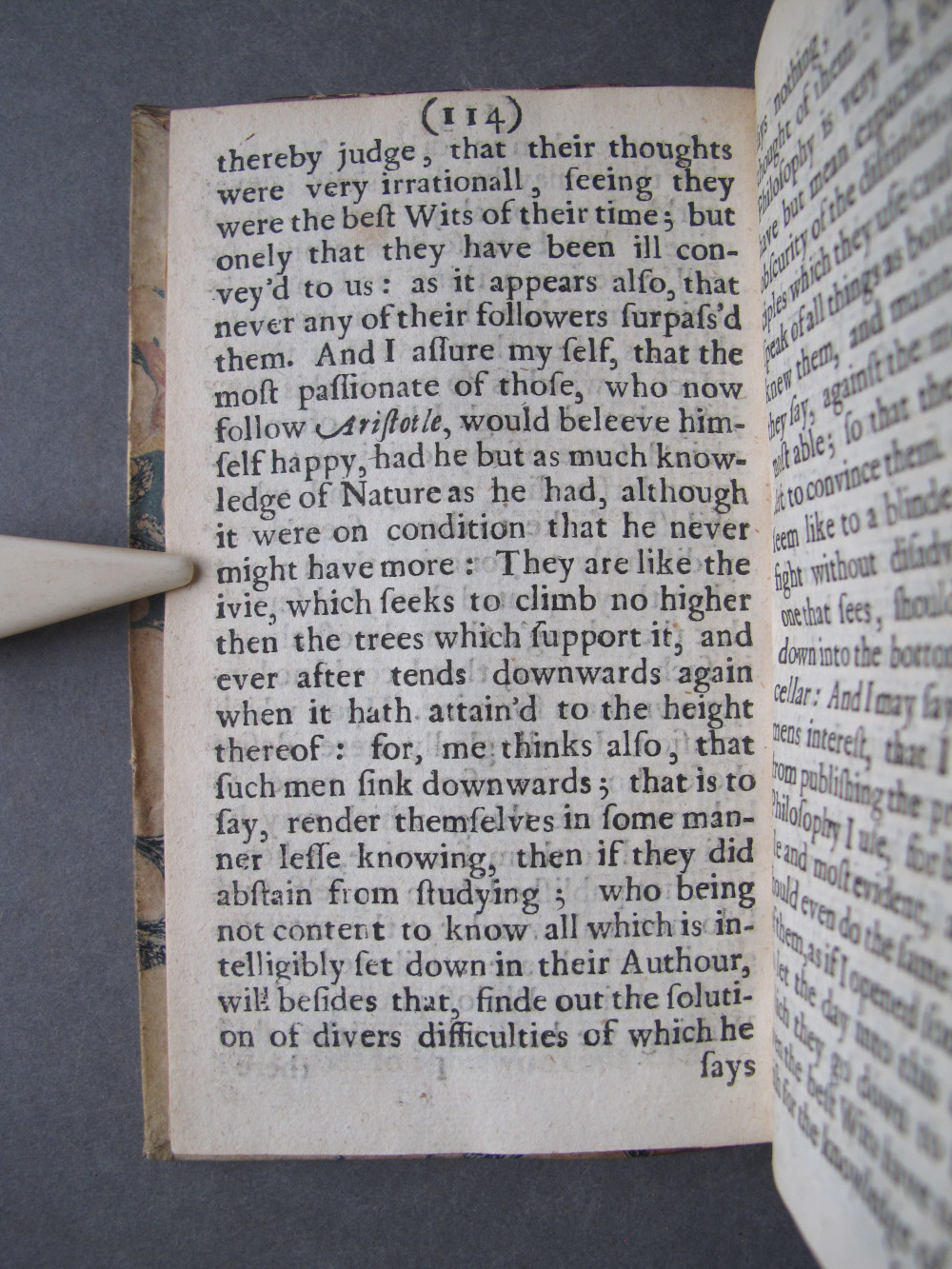

[Image 132 / 152]

(Page 114)

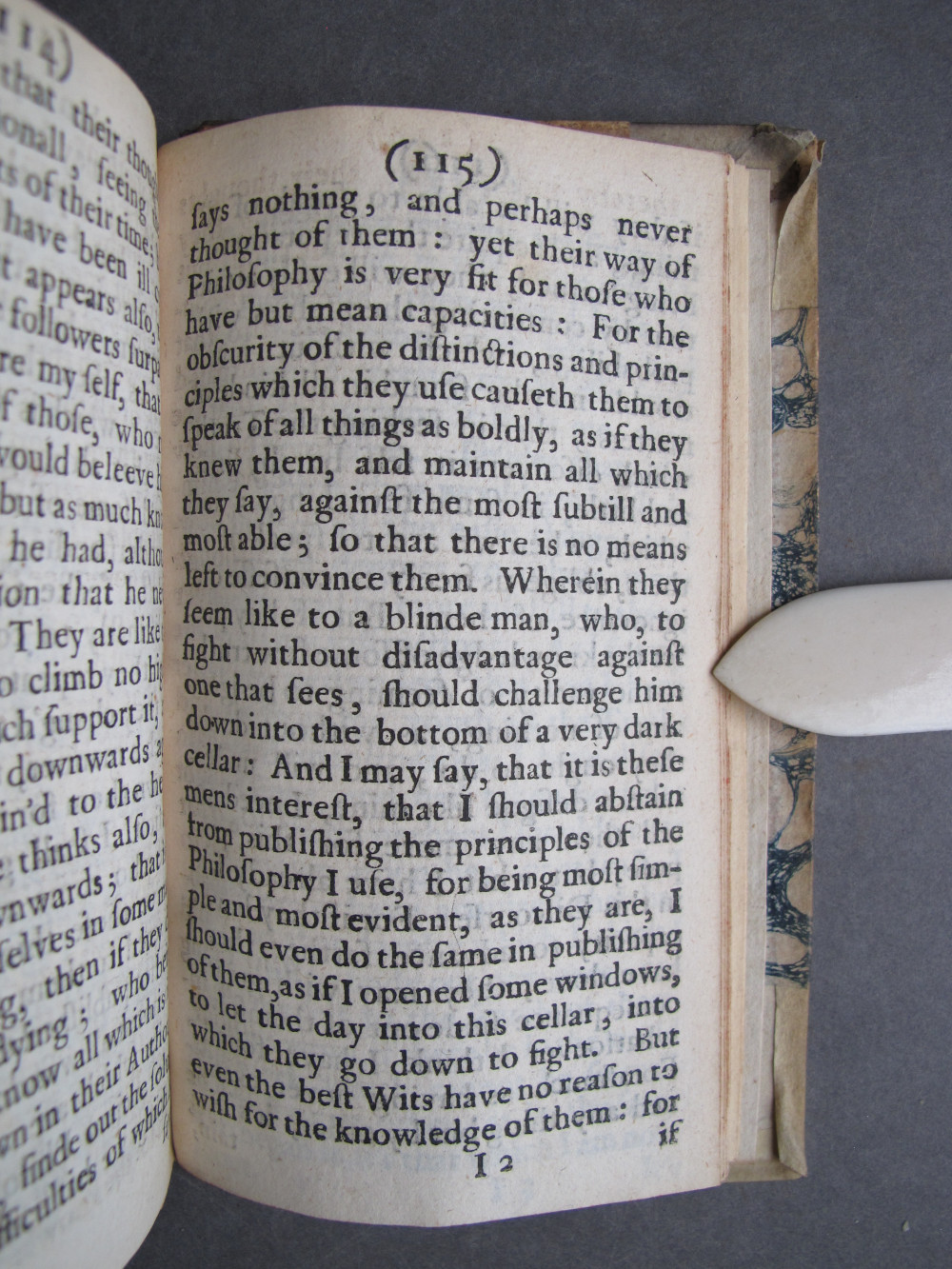

[Image 133 / 152]

(Page 115)

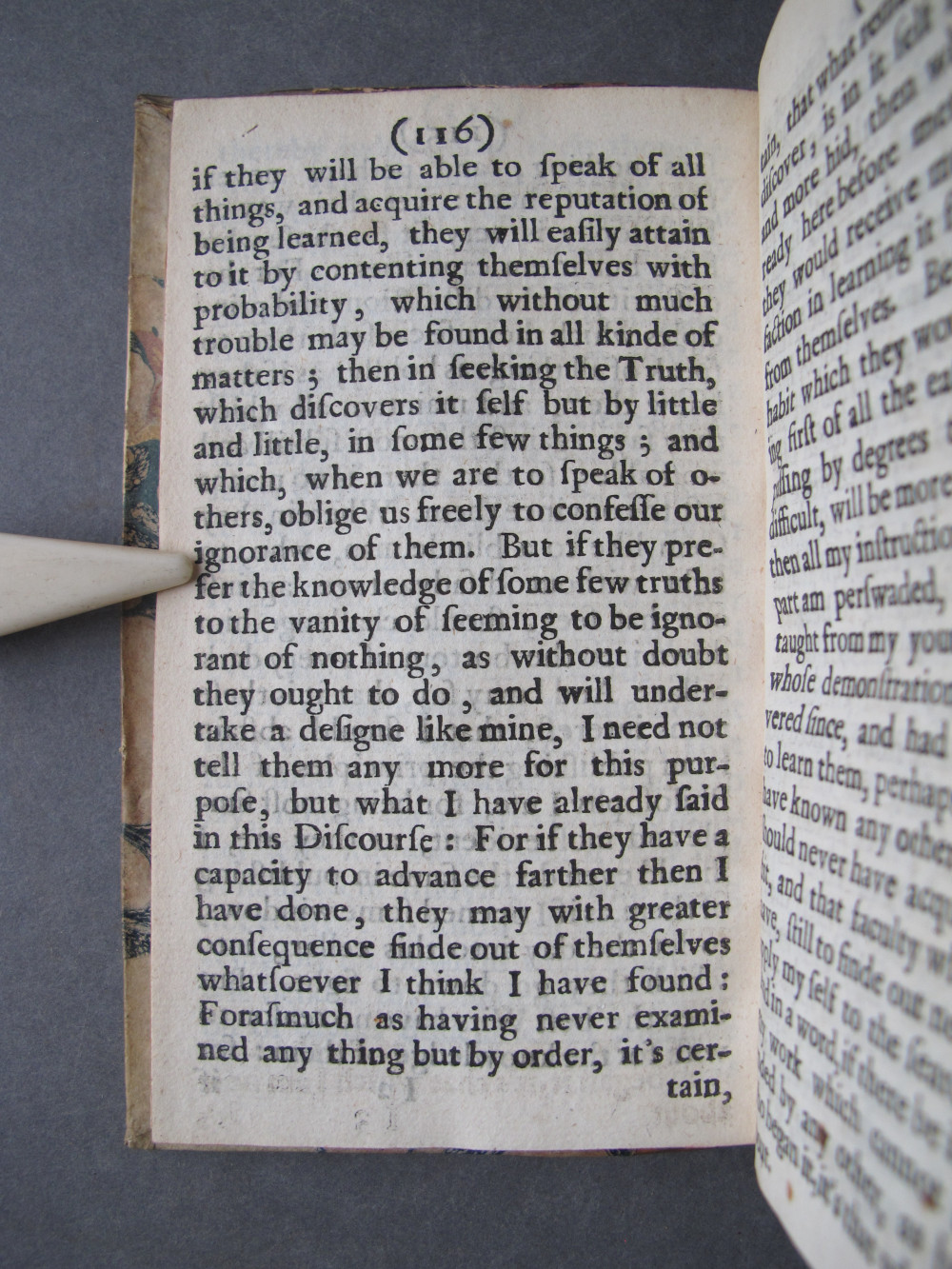

[Image 134 / 152]

(Page 116)

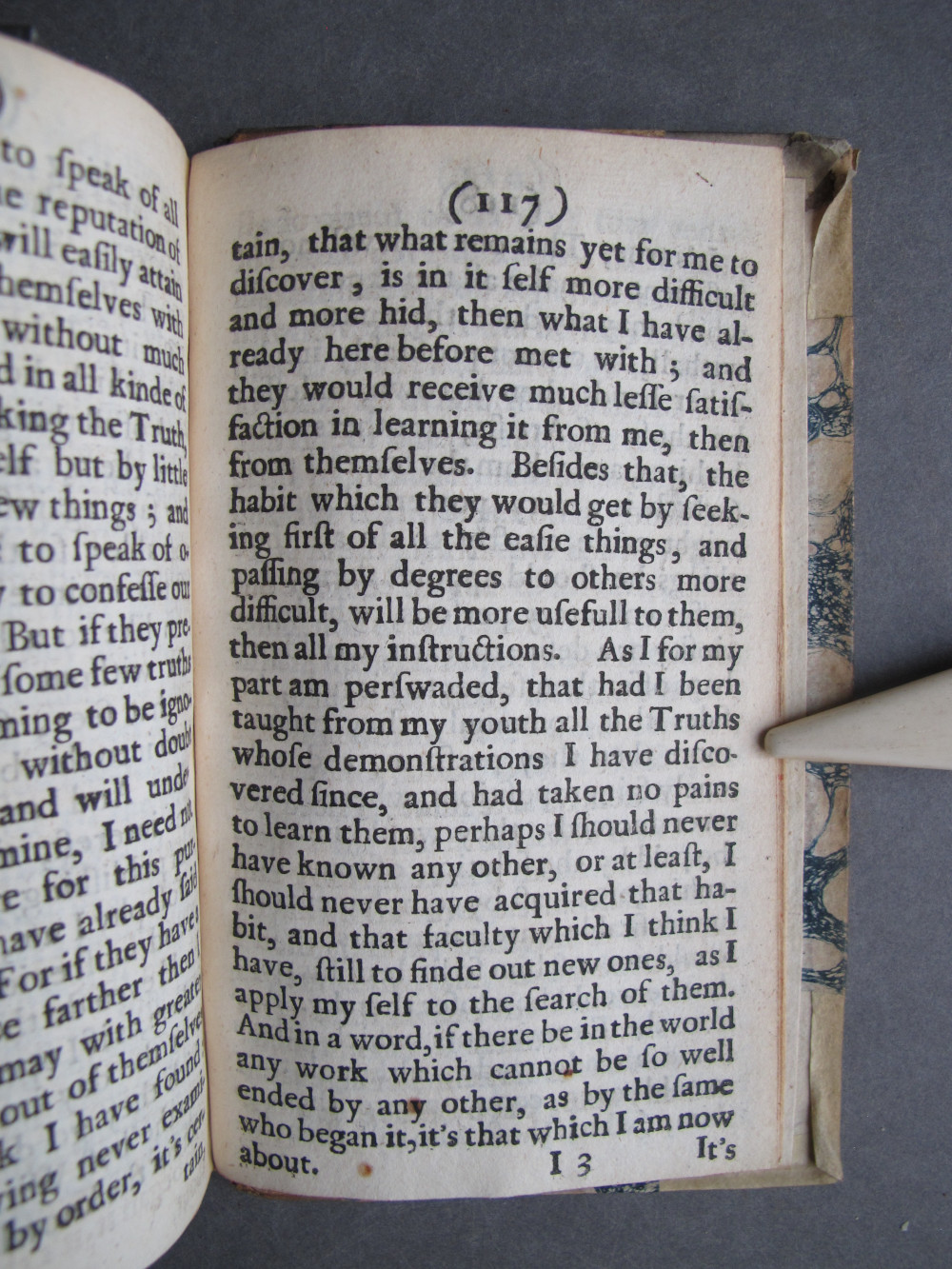

[Image 135 / 152]

(Page 117)

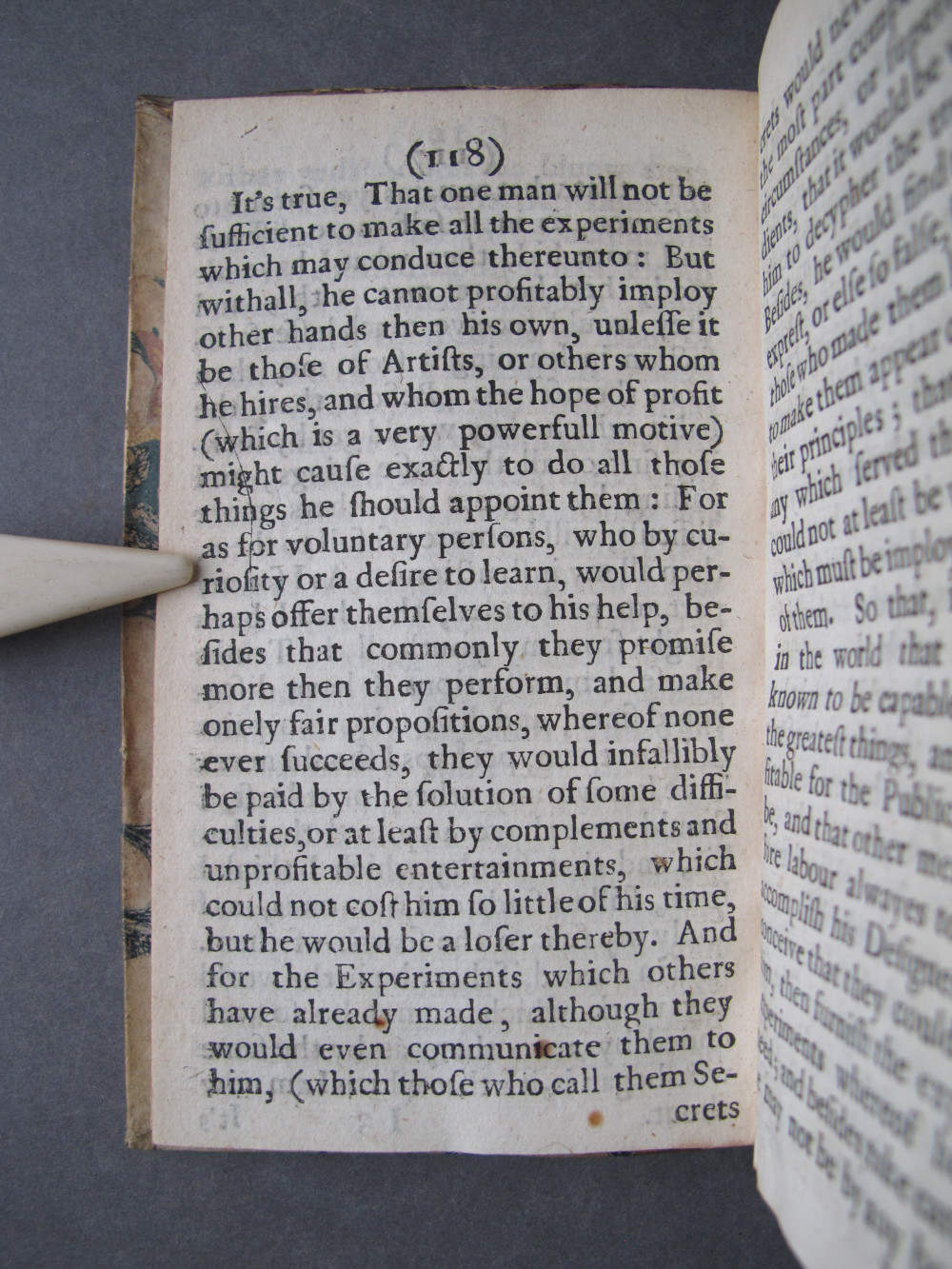

[Image 136 / 152]

(Page 118)

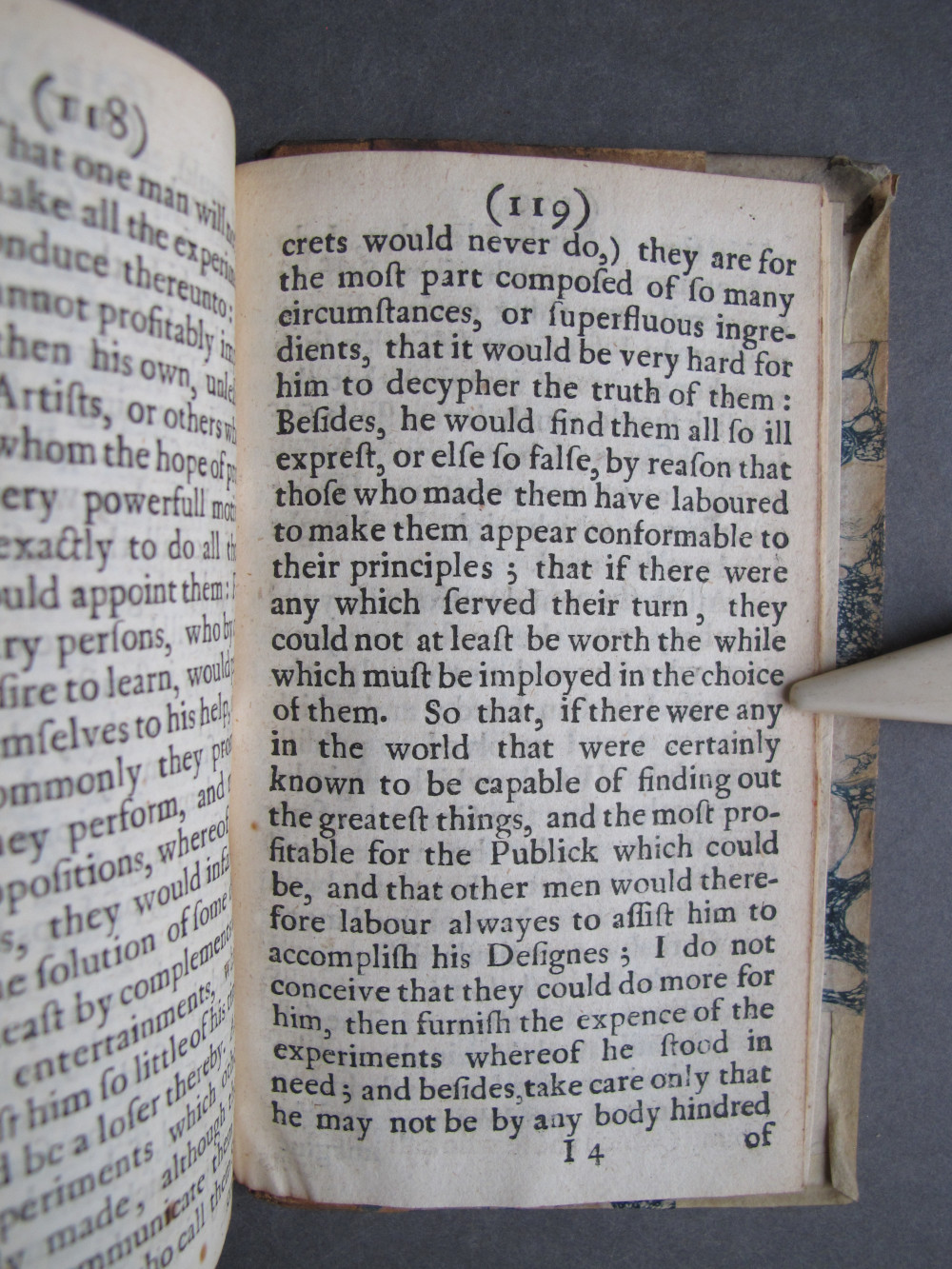

[Image 137 / 152]

(Page 119)

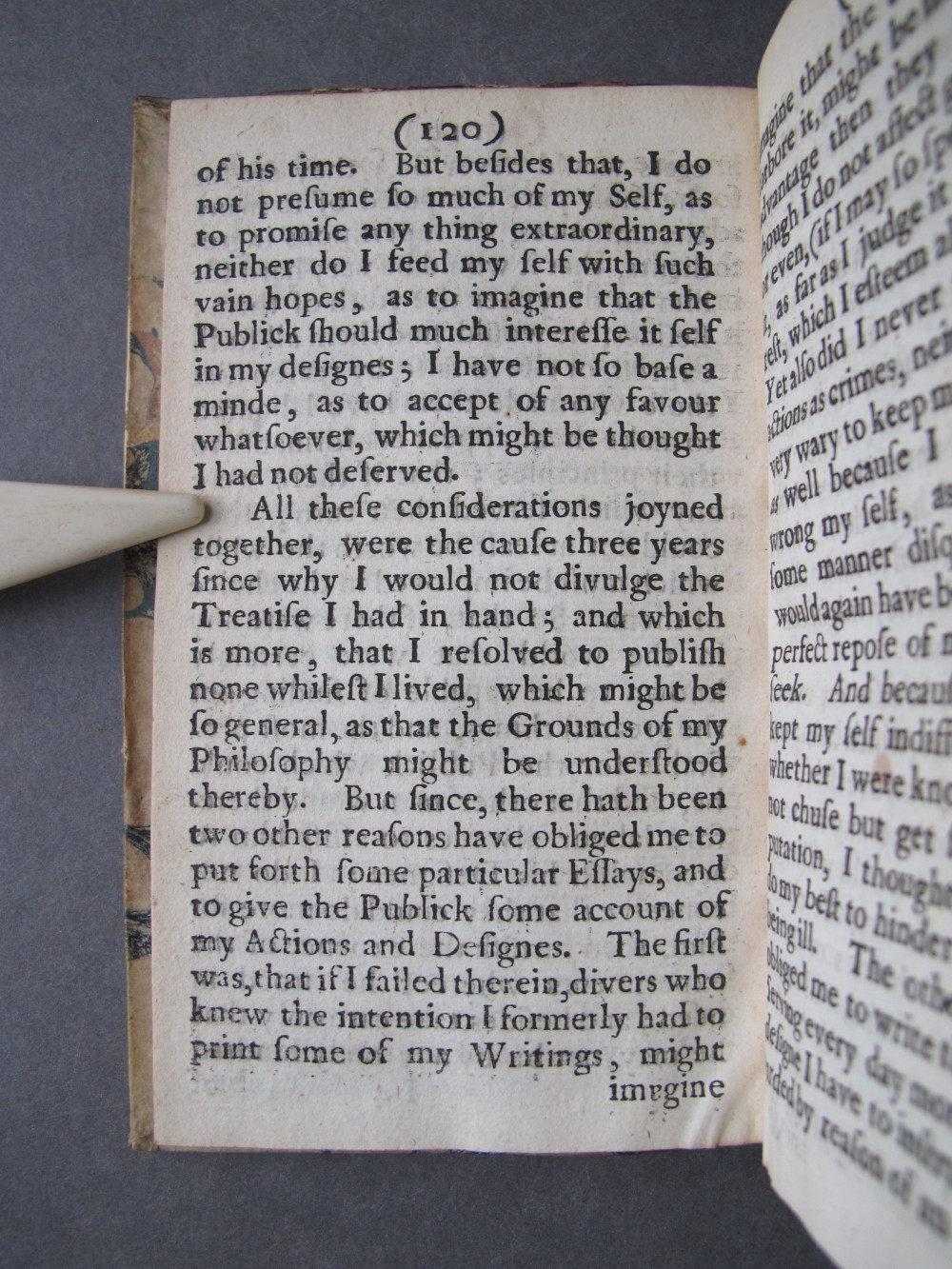

[Image 138 / 152]

(Page 120)

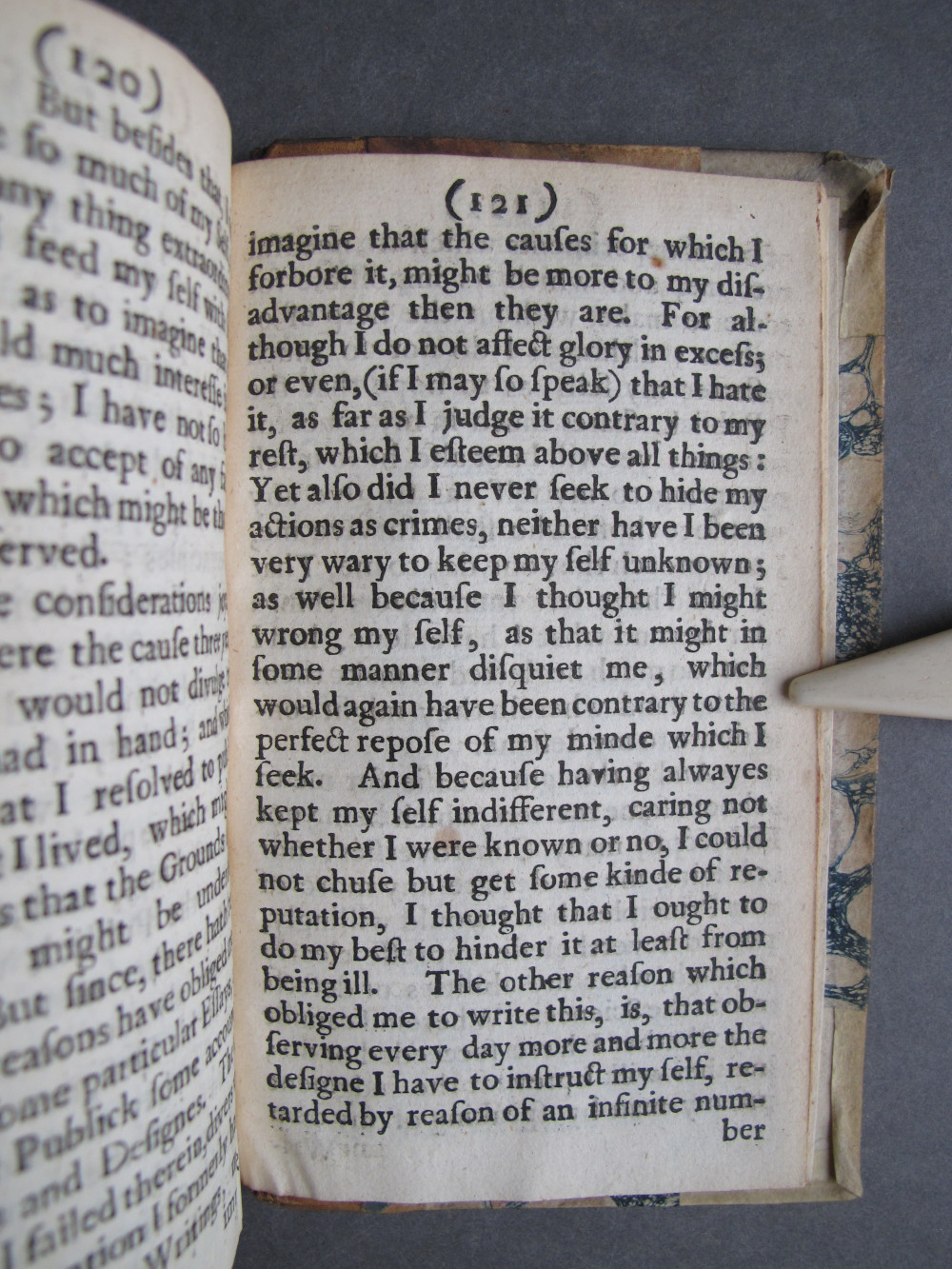

[Image 139 / 152]

(Page 121)

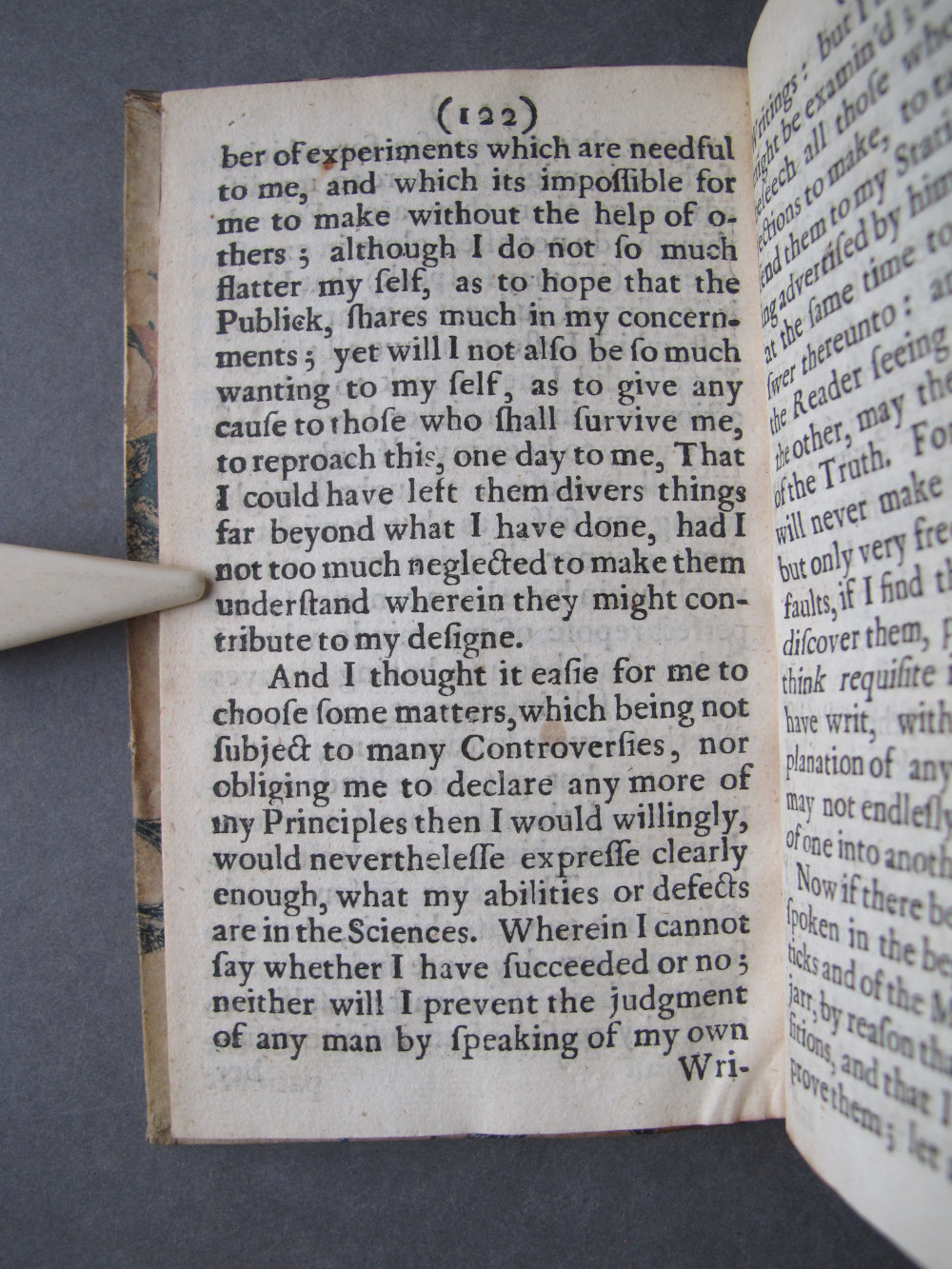

[Image 140 / 152]

(Page 122)

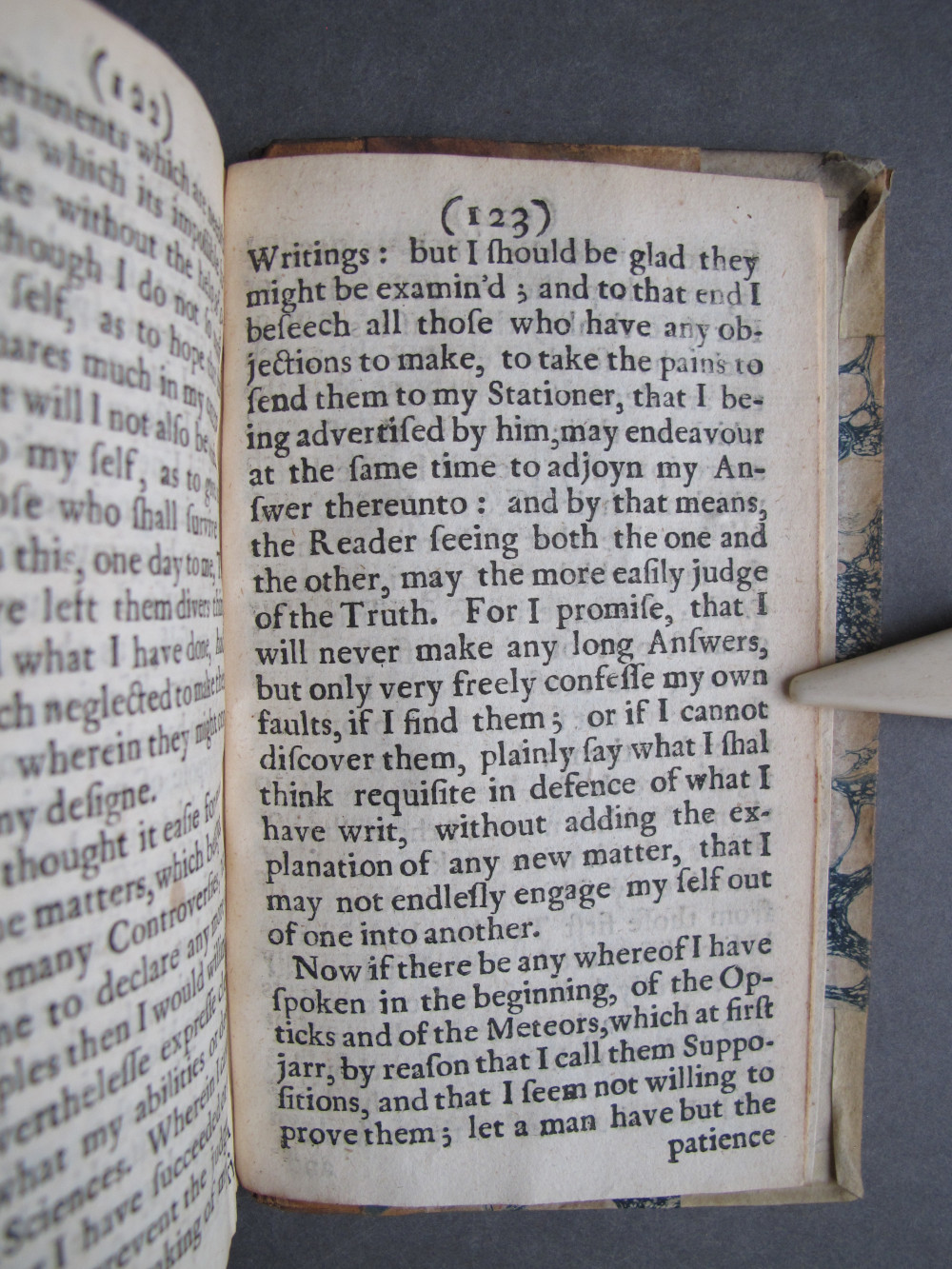

[Image 141 / 152]

(Page 123)

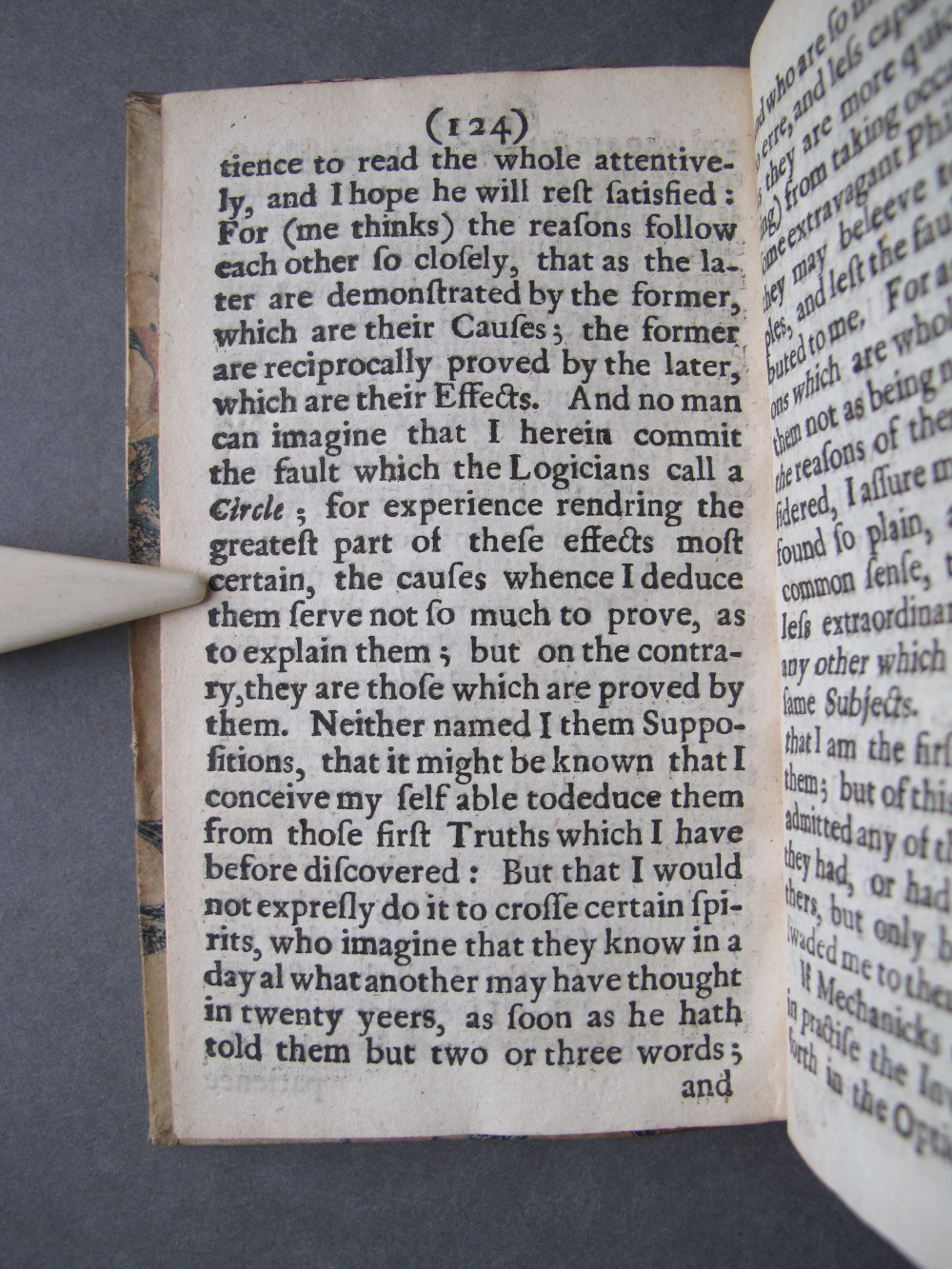

[Image 142 / 152]

(Page 124)

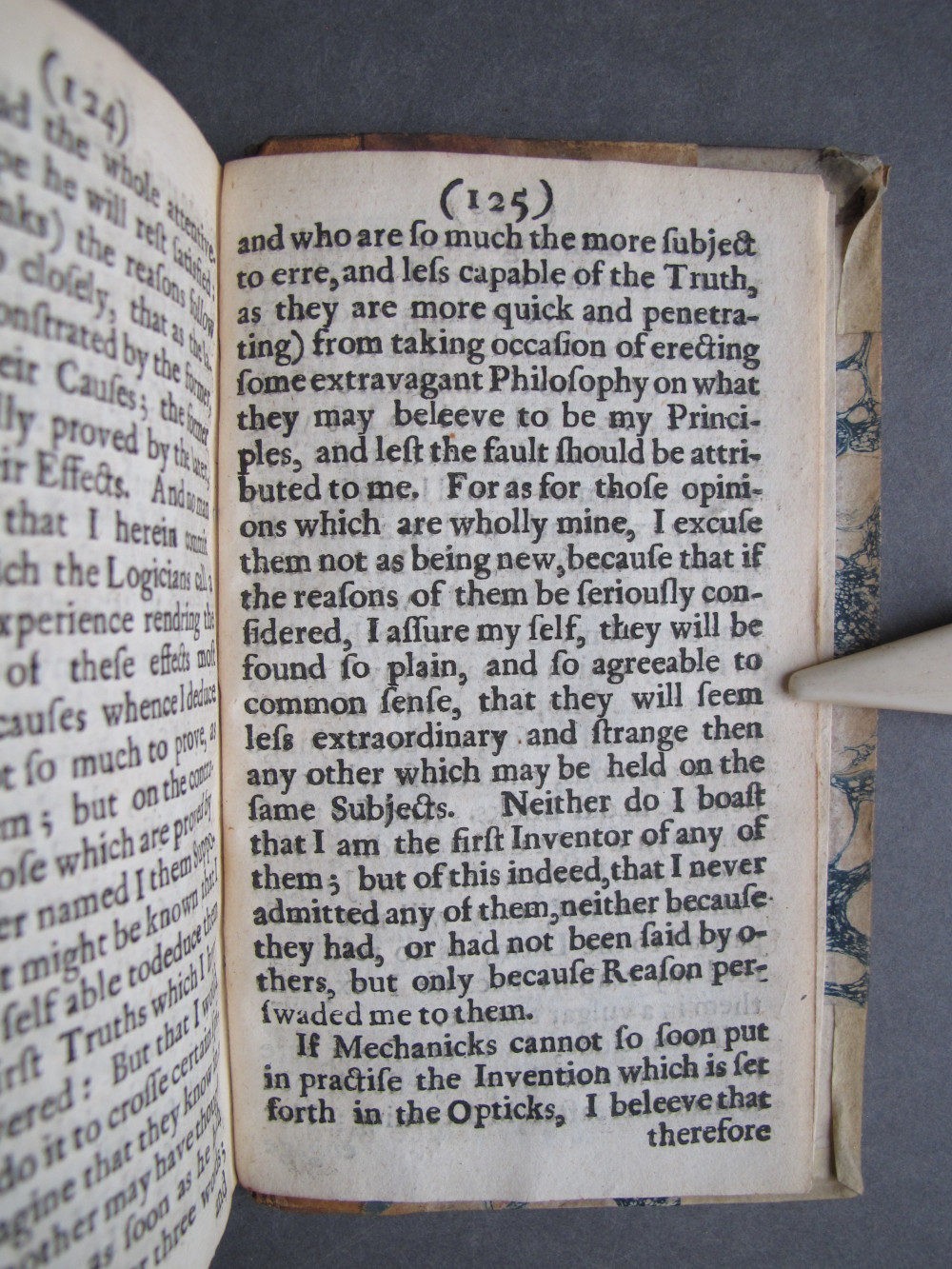

[Image 143 / 152]

(Page 125)

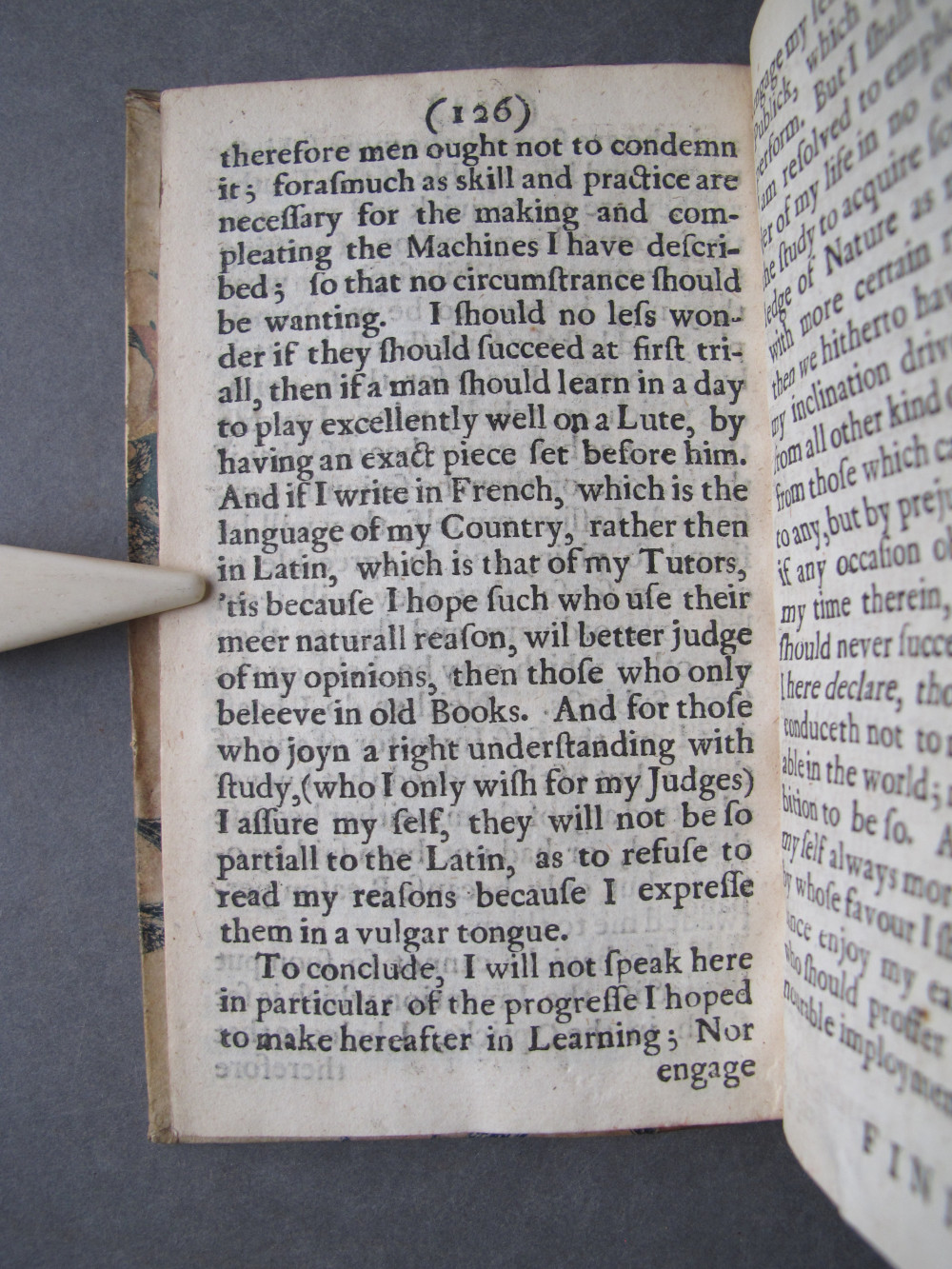

[Image 144 / 152]

(Page 126)

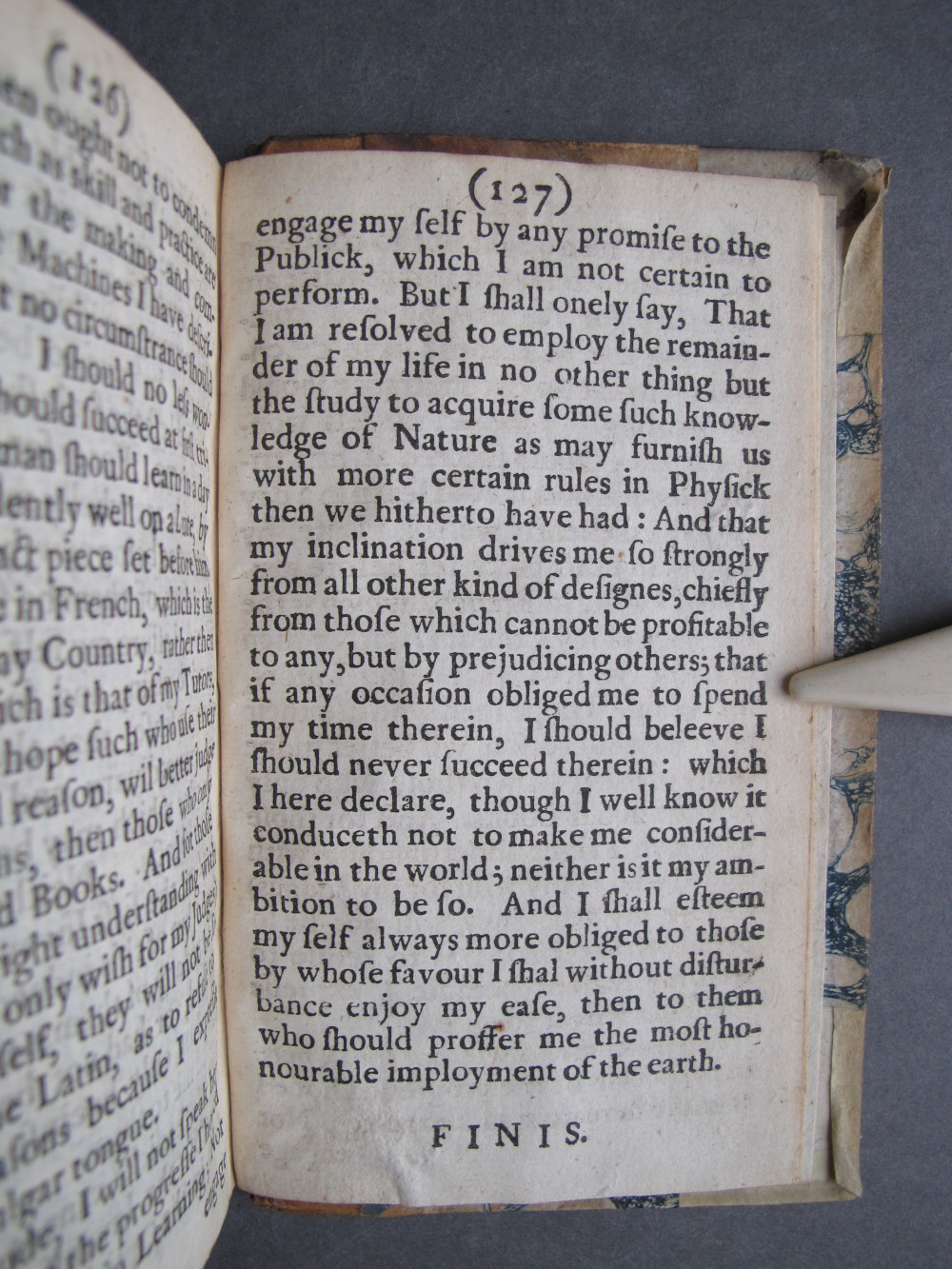

[Image 145 / 152]

(Page 127)

[Image 146 / 152]

[Image 147 / 152]

[Image 148 / 152]

[Image 149 / 152]

[Image 150 / 152]

[Image 151 / 152]

(Lower Pastedown)

[Image 152 / 152]

(Binding)

Download all files (.zip) Download transcribed text (.txt) Copy a link to the current image