Preface

A glorious lockdown task to do at home in 2021 was to write a description of All Souls Manuscript 129, by Water, as he calls himself, Morgan, an untitled description of his years as a soldier in the Low Countries. Photographs taken by All Souls Librarian-in-Charge Gaye Morgan enabled this task. Having already written too much for the brief description it was meant to be, there is far more I could write about this fascinating work.

Duncan Caldecott-Baird's The Expedition in Holland 1572-1574 ... from the manuscript of Walter Morgan (London, 1976) will give you a complete transcription, reproductions of all the illustrations and commentary; I have tried not to repeat him. The title is inaccurate really as Holland was then only a part of the Low Countries north of Zeeland. Other sources to augment or examine Morgan's descriptions include three contemporary sources, each of which give eyewitness accounts: the illustrator Franz Hogenberg; the poet soldier Sir, later Captain, George Gascoigne and his The ffruites of Warre, Dulce Bellum Inexpertis Est and his Voyage into Holande both written for Lord Grey of Wilton; Captain Sir Roger Williams The Actions of the Lowe Countries written for Sir Francis Bacon1. The most useful and interesting modern work on the history of the wars is The Eighty Years War: From Revolt to Regular War 1568-1648, edited by Petra Groen (Leiden, 2019).

The illustrations reproduced in this paper from the MS are details. The minuteness of all Morgan's illustrations makes the choosing of certain details the best way of illustrating this paper. The complete MS is available on the Library's website. This paper is merely an introduction to Walter Morgan and his martial affairs. The four final maps, figures 37 to 40, are contemporary maps which Walter Morgan may have seen and which are referred to in this text.

Bibliographic description

The manuscript consists of around 100 leaves of thick white paper. It is finely bound by All Souls College in white vellum in the late 18th century. The front and back covers have fine insertions of oval leather medallions with the arms of Lord Burghley. The pastedowns are marbled in blue and white. It looks like the book was created with truncated pages and that folio leaves were glued to these truncations. Consisting of eighteen double page illustrations preceded by descriptive text. The final fifty leaves are blank.

The leaves look as though they have bevelled edges i.e. uncut (figure 10 shows this) and that two leaves are produced from single whole sheets with versos often blank. The illustrations seem to have been executed first, then folded in half with the front outside blank becoming the textual description of that action and the back outside being left blank. Figures 2, 23, 31 show a middle fold clearly. No watermarks are visible.

Text, contents and condition

The front verso paste down has college shelf marks and notes. The next following page is where the MS begins, starting with four blank endpapers including two pastedowns and two leaves. Two blank manuscript leaves are followed by thirty pages of text with accompanying illustrative maps or figures in 18 chapters. Each chapter, as well as the dedication, begins with a centred introduction of a few lines. There are no catchwords. The page numbering where it occurs was probably added at a later date, sometimes in pencil, possibly by Narcissus Luttrell, who owned the manuscript in 1687. Figure 2 shows pencil numbering in a hand different from Luttrell's, possibly by Luttrell's sister's grandson, Luttrell Wynne, who owned the manuscript in 1786, or by All Souls once the college owned it.

Dedicated to Lord Burghley there is no suggestion that this work was anything other than commissioned by Cecil so some of the corrections may be his. Morgan writes a short description of each action he describes, followed by illustrative maps of the same which he calls figures. Numbering of illustrations and of text pages differs. When there, the number is at the top right hand corner verso and top left recto (figure 2). Numerous neat round holes are visible, which are probably worm holes, for instance in the fall of Brill and the siege of Rotterdam (figures 17 and 4). The siege of Mons has what looks like two sticks sketched in the top right hand corner though this might be marks from a pin as it is mirrored on the facing page where it looks like a pin, or a pin and a stick or another wormhole (figure 2). The text of the siege of Mons shows the sheet has been folded in half at some stage and there are a few stains.

There are certain additions to the MS made when it was accessioned by ASC, for instance, the first manuscript page, the title page which is also the dedication, Morgan's preface, has "Liber Col Omn, Anim : Fidel : Defunct : in Oxon :" and opposite this "129". Narcissus Luttrell has signed the book on the third leaf "Nar. Luttrel: His book 1687" (figure 35).

There are various library marks on the endpapers and on the pastedown inside the front cover, a pasted-in library plate.

Double ruled lines can be seen throughout the text which has a habit of falling off to the right. The text is written with a thick nib. There are a few examples of marginalia; for example "Coūt Mark" is added carelessly, spoiling neat text, with a thin nib, possibly by Cecil, in the margin of the section on the taking of Brill. This is interesting and it may be this particular action is pointed out because Morgan declares Brill "the chife keye out of the sea too the counry of holonde". The sack of Rotterdam began on 9th April 1572 and this date is added in the right-hand margin in a later hand, also with a thin nib or pencil. Morgan's spelling of names is fluid.

Somewhat surprisingly perhaps Morgan makes corrections to the text. He uses carets and the corrections are very clear. For example, it seems that he added the word "desire" to the preface. He has done this throughout using a fine nib though it is possible these additions were made at a later date. Other additions or corrections include what could be a couple of corrections to the summary of the text of the sack of Rotterdam where "and direction" and "1572" appear altered (see figure 3). The same alteration to the date appears in the summary for the fall of Brill. On this same page there are many examples of textual additions or corrections. For example, a letter has been erased and then an "in" added in the original hand but a "too" in a more modern hand has also been added with an inserted caret in pencil. Some of the text is a bit haphazardly marked. This is especially noticeable in underlinings. Morgan rarely uses capital letters, though the word "beginning" twice has a capital b, and someone has read through parts of the text and underlined words and phrases haphazardly. It appears that only names have been underlined but places too have been drawn attention to. The underlining in the text of the siege of Goes is particularly clumsy where "syrr umphrey gillbert being" is underlined but the next town named is not. One obvious error, what seems to be a lacuna with "servant" omitted, is not corrected where, at the end of the dedication and prominently, Morgan signs "your honors hys humble too command water morgan".

Throughout transcriptions in this paper I have used v, u and s where we do now. Morgan consistently uses v at the start of words and u within words and I see no reason to follow this usage. I have also updated I for G, mainly used in Germany. Morgan's letters are uniform and clear though less so in the textual additions to his figures so it could be said he has a text hand and a glossing hand. He has few flourishes or curlicues; some are attached to compass roses and some to the first letters of a page text, for instance in the naval battle of Horne, the fall of Brill and the siege of Mons. Occasionally he adds a flourish mid text and at the end the siege of Ruermonde he adds a marvellous flourish to the g of "Auguste". There are few superscripts, one being viiid where the d is superscript and lxth where the th is superscript. Words ending y as in Germany are written ye but the y of July is written with y umlaut, Ϋ. His punctuation is interesting and I've not worked out its reasoning as it does not cause confusion because the flow of the language is so decorous. Full stops are not included at the end of the texts. Line ends are often justified with : or :: or sss; commas are used but I did not find any semi colons. I have not noted line ends when quoting Morgan's text though a double or triple colon is often used to justify lines.

Of more interest is that I can see no obvious mistakes in accompanying drawings which might suggest that on printing, the text would be corrected. The text about how Louis de Boisot took the castle of Rammekens for instance, is full of unwieldy underlinings while the accompanying figure is one of the most carefully drawn (figures 5, 6 and 34). It is likely that Morgan created, or rather copied, his illustrative maps with such care because he believed they would be etched for distribution but for some reason, maybe because the whole is unfinished, Lord Burghley never published the treatise. It is possible that copies of the MS were made which have yet to be rediscovered.

Morgan's text reads fluidly and with grace. He is witty and his metaphors imaginative. He uses plain language as suits a soldier but with a sprinkling of proverbs and idioms. His description of the sack of Rotterdam, quoted below describe waves of Spanish soldiers descending on the coastal towns: they "came down towards the chiffest tounes too the seawards of that countrye too trye the disspocisions of the inhabitaunts ther" and the prose rises and falls as water. Water, or liquid, runs through the description of the sack of Naarden, a town surrounded by water but undefended, and the townsmen, fearing the fury of the Spaniard, welcome the Duke:

the boorgomasters of the toune wente owte too meete hym wythe three or foure peesys of raenishe wyne bere and the best vituells they had : poore syllye men drounde in so vaen a conseypte as too thynke that drynke shoulde apeace the wrathe of [the] Spanyarde whom thurstyd so mooche for bloode

Two examples illustrate his wit and use of idioms. When Alba executes Counts Egmont and Horne, Morgan says the Prince of Orange in High Germany "thoughte hyt farr better too bende a badd swoorde in defence of this horibille morder then too yelde his hedd as the rhest on the pillowe of the spanitshe provigion for the nobilitie of that countreye". And Alba, realising that Orange will find it progressively hard to pay his soldiers, especially soldiers from the Holy Roman Empire who will not shake the frost from his beard any longer than his monthly wages are paid: "forgettinge not wythe all the nature of the allmaen be hyt neuer so beneficiall untoo hym not too shake the froste out of hys berde in the feelde anye tyme longer then hee ys monthlye paede hys wadgis:"

Morgan has a surprisingly panoramic view of the actions he describes while he was in the Queen's service. This could be inspired by the illustrations he clearly worked hard to reproduce and embellish.

Morgan's illustrations

Morgan's task was probably a written account for Lord Burghley and he may be added his figures of battles, or actions, simply because he could and because by doing so he produced a unique document for his patron. Morgan describes for Burghley, according to the dedication, "the nature. of the situacions in fyrme lande marel woods seas meares and ryuers howe th [a wormhole has eaten the 'e' of the] tounes weare besidgid the order of theyr encampings batteries esscales bretchis and assaults wythe encounters uppon the land and water". Morgan's illustrative matter is based mainly on his own experience and on maps and illustrations he will have seen. His imaginative details are what give the text and the accompanying figures their charm and make them aesthetically pleasing; they are at the same time historical documents. The care taken over his illustrations and the lack of corrections which are found in the accompanying texts, suggests that the illustrations are final versions of earlier drawings. Canals, dykes, roads, pathways, sandbanks and so on are often depicted in such minute detail that their accuracy is assumed. The attack and sack of Rotterdam is especially carefully drawn for example; this landscape with trees and a house nestled within them shows that Morgan was a practised draughtsman, whether or not he was reproducing another's work (figure 4).

The same can be said of the illustration of the siege of Middelburg where Rammekens and Flushing are illustrated in a finely finished frame. The sharply drawn details of the fort at Rammekens, mean it can be used now, over four centuries later, to locate the fort so long as the compass is ignored (figures 5 and 6) because although Flushing's large church is correctly oriented, the compass is not. Flushing, so often invaded, is shown to have a large hospital, seven housing districts and a mill pond outside the town walls. Orange's flags fly large from the harbour entries. Sandbanks are depicted, which played such an important part in sea battles in the Low Countries and the concomitant lightships stand by at Rammekens. A rolling trench is shown snaking its way east from the fort. From the details of figures 4 and 5 it seems clear that Morgan enjoyed his art. Maybe that is why he added illustrations to his reports; maybe Lord Burghley's eyebrows shot up in surprise when he saw them.

All the illustrations describe an action or actions, which may take place over a number of hours or days, some on land, some on water, making each figure a narrative. The maps are more like tapestries than conventional maps so in this paper I mostly follow Morgan's lead and call them figures. Critics agree that it is likely that Morgan used military maps already in circulation and may also have seen tactical drawings but he is clearly educated and maybe took pleasure in discovering other depictions of battles he had assisted at. Burghley may have directed him to study maps, perhaps those among Burghley's own collection. He may have seen works by other cartographers, such as Lodovico Guicciardini, Petro le Poivre and almost certainly by Franz Hogenberg, and copied their designs2. S. Groeneveld has written a fascinating study of Morgan's and his contemporaries' illustrations, which are mostly anonymous, to show how much Morgan copied and which details he added. The prints of Mons, where Morgan uses Anonymous' map and Roermond stand out, along with the sack of Naarden and the siege of Haarlem; the artists of these originals are all anonymous. The figures of Orange and his men at the siege of Mons (figure 24) are exactly the same as the anonymous illustration of the siege of Mons (figure 40). The anonymous artist of the sea battle at Rammekens has the same smoke formations Morgan uses but lacks Morgan's cattle and horses; however, Anonymous' depiction of the Amsterdam supply routes, when the boers and their allies were chased back into Amsterdam, even includes cattle similar to Morgan's and it also shows the push of pike, line for line matching Morgan's copy. Anonymous' siege of Alkmaar even includes the same lollipop trees which Morgan depicts and in the same positions3. Caldecott-Baird has already shown the similarity between the anonymous print of the sack of Haarlem with Morgan's figure of the same. As it seems clear that Morgan copied most if not all of his figures, this goes some way to explaining why they are so neat and uncorrected. Of course the origin of his prints does not take away the pleasure they give to his readers.

Morgan's Flushing (figure 6) matches Braun and Hogenberg's 1610 map (figure 39) in almost every detail except Hogenberg shows no hospital outside the town walls and the gallows have been moved outside the walls; maybe the hospital had been destroyed in the intervening years. It is certain that Morgan knew Flushing and Rammekens but there is another reason I believe Morgan used somebody else's map which is because he marks Flushing Vlissinge which is almost the Dutch Vlissingen. In the accompanying text, the town is the anglicised Floushynge and it is the same in his illustration of the battle of Rammekens (figure 5). Another difference is that the map of Flushing and Rammekens includes a key which seems not to refer to anything noted in the map; Morgan, unusually, forgot to annotate the town's gates, Head Gate, Prison Gate, Ramekin Gate, Myle Gate etc (figure 16).

The siege of Haarlem, 1st June 1573, also features a key and far more explanatory text than any of the other illustrations (and in fact I am happier calling it a map). The key to the map is referenced in the accompanying text noting the Duke's and the Prince's trenches and also the names of Haarlem's gates (figure 7). The siege of Haarlem was probably the first action Morgan took part in which might explain the detail of his description. His text includes details of the accompanying figure such as "the duks trenchys ys notyd wythe:A:t: and the prynce hys trenchis wythe:p.t :" (figure 8). This map is also correctly oriented and probable that Morgan took part in this action. The text on the map appears to be the same hand as the accompanying text and it explains that a way was cut through the dyke so that the king's ships can come from Amsterdam to Haarlem. The text reads "A waye cutte thorowe thys dyke too come from Amsterdam to harlem mear withe the kings shipps".

Another illustration with explanatory text, this time of the battle over supply routes in the same area, Haarlem Mere, but shown a bit further north, reads "the newe waye cutte thorowe the sea wall to harlom meare". As the Spanish ships from Amsterdam try to relieve Alba's camp at Haarlem on 5th June 1573, Walloons are shown protecting another cut dyke from the Duke's men of Amsterdam and Utrecht (figure 9). The accompanying text describes how the Duke's men underestimated the Prince's Walloons and "wythe in shorte tyme wherof the fighte became verye whott betwixte them" and the cattle nearby look ever so slightly surprised (figure 10).

Morgan will have seen many of Hogenberg's maps of the same towns or even of the same actions. Morgan's illustrations of the sieges of Mons and Roermond could, with slight differences, both be by Hogenberg or the anonymous artist. The lines of cannons and the single figures of gens d'armes for instance match in Morgan's and Hogenberg's Roermond and Morgan's Mons, figure 24 is very similar to figure 40, Mons by Anonymous. Hogenberg is the better draughtsman, which is not surprising as Morgan was primarily a soldier, and his details are crisper but Morgan's placing of the town, of the soldiers, of resting captains in their tents, of the victuallers, the position of cannon, the naming of the Prince's army, the attitudes of many of the figures match Hogenberg's4.

The few portraits Morgan includes are not innovative, except maybe for a couple, and appear to follow a pattern which Hogenberg also uses so the giant figure of a commander such as Alba, shown in the siege of Mons gazing out of the frame calmly in the midst of battle and repeated in the illustration of the sack of Naarden (figures 21, 26 and Hogenberg's Roermond, figure 38) and which appears more than once in different scales, is based on Titian's painting of Charles V on horseback5. The depiction of the siege of Mons shows six major commanders, all on horseback, though one, having been hit, is falling off his horse. On the Spanish side are Vitelli, Julian Romero and Alba; on the Prince's side are Drunnen falling from his horse, the Prince and Mandersloo. The one exception to a stock character is Romero at Mons, whose horse bucks violently (figures 24-27).

Morgan shows major and often named players in particular incidents larger than the surrounding battle. The illustration of the fall of Brill matches the text which tells us how the burgesses of Brill were misled when they climbed up onto the town walls and took the whole tercio at their feet to be seasoned soldiers while in fact Counte Marke had placed "theyr droomms trompetts and enseygnes wythe a fewe armd men that they hadd in the for fronte of theyr batell too keepe covert the rheste beynge maryners". That and the aid of fire at the gates forced the town to yield. The importance to the outcome of these ensigns and musicians at the front is clear because the trumpeter is drawn larger than the soldiers in the body of the battle (figure 17).

Most of the ordinary people Morgan highlights are copied, even in the fall of Mons, where women are shown running for their lives, each with her dog, one with a bread iron on her shoulder and another woman with a cockerel on the bag she's carrying on her back, while behind them Louis, the Prince of Orange's brother who is mortally ill, is carried out of the town (figure 29). It is thought that Morgan was not present at Mons so both his illustrations of the town are from others' descriptions and others' maps and drawings. Many maps of the era include people but they normally do not take part in the action and are instead shown at the map's edge as in Braun and Hogenberg's map of Flushing (figure 39).

Morgan's written humour is certainly reflected in his drawing. He included many idiosyncratic details to his figures, such as the dog single-handedly sailing a hoy up the Scheldt, towards Goes (figure 11). In fact the dog is a historical figure, a hero, and probably refers to a story Williams recalls of how the Prince of Orange's life was saved during the siege of Mons by his dog, a Dutch pug6, who woke him by "scratching and crying, and withall leapt on the Princes face" and ever since then, many commanders kept dogs with them: "For troth, euer since, vntill the Princes dying day, he kept one of that dogs race; so did many of his friends and followers. The most or all of these dogs were white little hounds, with crooked noses, called Camuses."7 Morgan was at Goes, where he was one of a few captains present fighting for the rebels and leading in the van, however it is doubtful he saw a dog sailing a hoy.

Frames

Each figure has a decorative border within the page to frame the illustration. They are variously ornate. The sack of Rotterdam has scallop shells within two ropes and an outer knot pattern in bold (figure 4). The fall of Roermond has daisies or sunbursts within two ropes and a bold outer knot pattern within an outer rope (figure 12). Other illustrations follow a similar design or have a single rope-patterned frame. The fall of Brill has a simple pattern but the siege of Goes and the sack of Naarden are somewhat surprisingly decorated with hearts (figures 21 and 30).

The frames' complications vary and maybe show increasing confidence though it is impossible to know in which order the figures were created. The siege of Mons lacks detail in the left frame which is present in the right implying possibly an unfinished border as points included in the top, left and bottom of the frame are not added to the right hand side (figure 14). The frequent cannon ball design has them either in pairs or more often using three cannon balls. A cannon ball design could be seen as the appropriate presentation of the picture it contains and as such, it is decorous and shows respect for Burghley as it displays the artist's attention to detail. The sieges of Roermond and Mechelen have the most intricate borders although two of the companies illustrated at the siege of Roermond are unfinished (compare the companies in figures 12 and 14). By comparison, Guicciardini's maps tend to have plain borders and Mercator's are far more ornate but Hogenberg's borders, when present, can be similar to Morgan's, especially his use of dots or cannon balls and crescents or horseshoes (see Braun and Hogenberg's Civitates Orbis Terrarum, 1572).

Particularly interesting is Rotterdam church spire which, uniquely, stabs through the frame. To allow the spire to break playfully through the border adds to its immediacy, all the more so as frames distance and formalise pictures while making the contents of the frame appear accurate (figure 13). This is precisely the way Morgan uses witty turns of phrase to bring alive his descriptions. The other figures cut off spires and tall buildings at the frame, for instance in the town of Mons where they are squeezed into the frame's edge, Morgan relying on our own imaginations to complete the skyline (figure 15).

Compass roses

It appears that Morgan added the compass roses to the illustrations he copied and most of the illustrations have a compass rose, often by the top border. This would make his illustrations more accurate than those of Anonymous, for instance. Those which do not include a compass are the sack of Mechelen and the siege of Mons. These towns are both inland and maybe that is why they are not oriented with a compass though of course the fall of Mons has a compass as does Roermond so the lack of compass in these two is probably insignificant and their addition may simply have been forgotten.

Most compass roses are drawn in full and include the points Northe, Southe, Weste written at the points, usually with North pointing to the left and West to the bottom of the page. It is a recent fashion to orient all maps to the North. East is often omitted which suggests that the drawings are generally oriented to the East, two of the drawings accurately use North, which is surprising because for Morgan in the Low Countries, England is the most important land so one would expect the maps to be oriented West. He can't always have approached the towns from the West. The map of the fall of Mons has North where we now would expect it to be as does the illustration of the Drowned Lands. Initially it looks as though the map of Goes is also seen from the South with the compass oriented North but in fact Morgan shows us the town and Sir Humphrey Gilbert's camisado from the North. This is probably because he needed to add details of Gilbert's attack. Cristóbal de Mondragon marched his tercios to approach Goes from the East through shoulder-deep water of the Scheldt in order to surprise the rebels and thus relieve the town, so Mondragon's soldiers are about to appear unexpectedly and overland from the left of Morgan's figure; le Poivre sees the town from the other side, i.e. from the South in his map of the same action (figures 30 and 37) which suggests interestingly that Morgan's illustration was entirely his own.

Geertruidenberg, Flushing and Rammekens compasses have long curlicues falling from points of the compass and the sack of Haarlem compass points quarter the picture, with straight lines from N, S, W and in between SW, NW, SE. The south compass point below Middelburg and above Flushing curls delightfully round woodland and text beneath Middelburgh (figure 16).

The compass roses on depictions of action at sea are not, as might be expected, mariners' compasses, except for one: the illustration of the Drowned Land is oriented North and has no West noted. The compass is in the middle of the page with points of the prevailing winds marked in Latin which is more usual on astrolabes or wind roses found on sea charts than land maps: Septentrio, Oriens, Meridies and no Occidens (figure 18). It is more accurate, of course, to use a shipmaster's navigation aid for a sea battle and maybe suggests that Morgan copied this picture from a different source than the other pictures or that he took advice from a mariner, particularly as the illustration of the siege of Haarlem, one of the most detailed and most inclusive drawings in the book, with the Tie on one side and "Harlem Meare" on the other side, therefore largely sea, has the usual land compass rose with East at the top.

Historical background

Walter Morgan was a veteran of the Dutch wars from 1572 to early 1574. The following is not a detailed history but observations where relevant to Morgan's actions and drawing on the contemporary accounts of Williams, Gilbert and Gascoigne. The Dutch wars, or the rebellion of northern Dutch against the occupation of Catholic Spain, began in Gelderland a full 50 years before Morgan landed in Zeeland and later became the Eighty Years War. It was as much a civil war in the Seventeen Provinces between northern mainly Protestant, Lutheran and Calvinist Dutch for the Prince of Orange and southern mainly Catholic Dutch who fought for Spain. Orange, brought up in the court of Mary of Hungary and Burgundy, was Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht from 1559 though not continually, and Admiral General from 1572 when the Dutch took Veere arsenal, and he was an experienced politician. To Morgan, Orange is "the exelent vertuous and prudent lorde".

Walter Morgan fought for the Prince of Orange alongside French Huguenots, Germans, English, Scots, Irish, Welsh, Burgundians from Lorraine, Gascons, Landskechts and Reiters from the Holy Roman Empire. At Goes, Morgan was one of a few captains present fighting for the rebels, leading in the van with Frenchemen and Scots as he was at the siege of Haarlem according to Williams:

The Duke with the rest of his army stood in battell within the trenches. Our Generall and Chiefes placed our Waggons to frontier the fairest places where their horsemen could charge vs: our Walloons, Dutch and Flemish, stood within the Waggons in good order of battaile, all in one squadron with our horsemen on both the sides towards the enemies, our English, French and Scots stood, some twenty score before the front of our battaile.(Williams, p. 129).

At the siege of Haarlem, for example, there were around 200 English in various companies. The Scottish contingent was strong, the Scottish Wool Staple being in Veere, which the Scots called Camfer, as does Morgan. As recently as 1551 James I's daughter married into the ruling family of Veere and there is a Veere tartan. Alba's Spanish army was similarly constituted and also included tercios from Naples, Sicily, Sardinia and other city states. Soldiers from the old Habsburg Empire fought on both sides according to religion and to pay, for pay was a more important consideration for most soldiers than religion and the Spanish had a good reputation for paying their soldiers on time. Orange still needed to secure his tattered reputation for paying his soldiers. Other nationalities fought on both sides according to religion but there were Catholics who fought for Orange because they detested the Spanish occupation and because early in the uprising Orange promised them freedom of worship. Certainly Dutch soldiers and sailors could hold family allegiances in direct opposition to the side they were fighting for and as in any civil war, they frequently, if temporarily, changed sides for many reasons.

Dutch propaganda taught until recently that soldiers fighting for the fledgling republic were "Fremdkörper, composed of foreign riff-raff"8, however, the need to protect a town's prosperity from interlopers meant that all were involved not just paid foreign soldiers. It was during the long siege of Haarlem that the legendary Kenau Simonsdochter Hasselaer (1526– 1588) appeared. It seems she provided for the defenders and maybe lent a hand but the legend tells of a company of women soldiers. Williams seems pretty sure of his facts9. He says of the soldiers defending the town "They caused also about sixe hundred Burgesses to carry armes; besides two thousand and more of all sorts of people, sufficient to supply the place of pioneers: of which were some three hundred women, all vnder one Ensigne. The womens Captain was a most stout dame, named Captaine Margaret Kenalt." Morgan does not mention her.

Mercenary Landsknechts and Reiters from the Holy Roman Empire were indeed employed to garrison towns by the civic guard to keep the peace and to defend them in times of war because when towns were taken these soldiers were usually the first to be killed. In a way these Landsknechts were a standing army though normally on only three-to-six-month contracts. The Dutch navy, such as it was in 1572, were called the Sea Beggars or just the Beggars, Guezen in Dutch, because once 400 noblemen had begged Philip II for their peers to be Governors. They behaved with the cupidity of mercenaries much of the time.

The depiction of peasant life as separate from that of the soldiers in so many of Morgan's and contemporary maps may have resonance in modern Dutch unwillingness to consider the early modern Dutch as warlike; the paintings of Pieter Breugel the elder tell a different story. In reality it seems that everyone took part in these civil wars, men and women alike, from servants to shopkeepers and civic employees. Morgan often mentions the boers for example, the farmers, most of whom near Amsterdam supported Spain and did so with more courage than skill. They value only creature comforts according to Morgan's description of skirmishes around the supply routes near Middelburg, and having "vicited withe the soldiours for certen vituells and bedds" received no comfort from the Prince's soldiers, who are desperately trying to raise the siege of Haarlem so they make haste to Amsterdam with stories of Protestants razing farmland thinking, says Morgan, "wone of thes twoo thyngs eyther that hit was no greate matter too wynne a trench kepte so farre from a place of socourse because they had not fayre howsys too keepe them drye when hyt raend and fether bedds too lye softe uppon when they woolde sleepe" or that there had not been enough time to make the trenches defensible. The accompanying figure shows how the Prince's men outwitted the Duke's men and boers of Amsterdam, 800 of whom were killed. It is true, however, that the Prince's men were mainly "frenchemen walons and lansquenights".

The Low Countries were occupied by Catholic Spain, headed by a Governor who, during Morgan's time, was the Duke of Alba followed briefly by Luis de Requesens. Many towns in the northern area, which Morgan seems to know best, remained in Spanish hands in the Low Countries such as Antwerp, Middelburg, Amsterdam. Previously Charles V had followed the Burgundian method of using a local intermediary to control the Low Countries and they were governed by someone considered local, latterly Mary of Hungary. The change made by Philip II, from a member of the royal family managing the Low Countries to a soldier ruling, exacerbated grievances. The rebellion was motivated partly because of a 10% tax introduced in May 1572 taken from people living in small towns, who were already living in straightened circumstances, and that in sparsely populated areas the levy was not lowered. Religious differences and anger at placards placed throughout the Netherlands demanding the populace worship as Catholics caused further unrest. For Protestants living in poverty near to wealthy Catholic churches and monasteries, Philip II's taxes were further resented. The text of the sack of Rotterdam describes this well.

the newes cominge upp the countrey of holand of the takinge of the bryll count bossue chife comaunder ther. so establised by the duke of allva. knowinge theyr estate ther too be in that kynde of fikellnes that they weare readier too revolte withe theyr contrary religion for the hope of a comoditie then too paeye so greate a fyne as theyr tenthe penye came too for a religion holden more awncient then good of a greate nomber:assemblyd certen compenies of spaniards an walons from dorte and other placis wheare they weare apoyntyd in garisons and came downe towards the chiffeste tounes too the seawards of that countreye too trye the disspocisions of the inhabitaunts ther in alegeaunce towards the kynge of spaeygne

Alba was a veteran of many wars by the time he arrived in the Low Countries and Requesens' experience included fighting the Ottoman Empire beside Don John in Cyprus. The Spanish Catholic occupiers, or as Morgan writes in his text on Brill "thos bloodie tyraunts whom weare so ymportunatt of desire too swalowe upp : the fruits of theyr countrey and too brynge them too the serville yoke of bondaedge", could provide a mere 8-9000 seasoned soldiers in 1571 to maintain their position in the Netherlands. Spain was short of experienced soldiers because of the continuing battles on sea and land with the Ottoman Empire and by 1570 southern Spain was being invaded by the Turks; in 1571 the Spanish were fighting in Cyprus and a few months before Morgan began his report, when the crusading Holy League was recreated, the Spanish fleet had been virtually destroyed at Lepanto. It is improbable that most of the Spanish seriously considered the wars of religion in the Low Countries as a crusade although Philip II professed to and the leaders of the Dutch revolt were executed as heretics by Alba's Council of Troubles. Significantly, Morgan begins his first description with Alba's execution of Counts Egmont and Horne in Brussels, two of Orange's most trusted allies. Gilbert's comments after the St Bartholomew's Day massacre are decidedly anti-Catholic, calling Papists "the enemies of Christianity"10. Morgan is far less dramatic, appearing to understand that Catholics and Protestants are two sides of the same coin, "a religion holden more awncient then good" when writing of Catholics in Rotterdam. In any event, Morgan describes the core of the Spanish army as experienced and tough so at the siege of Haarlem, Alba is "cleane tyryd in mynde" that such seasoned soldiers could be held back by Haarlem's meagre defences. The strength of Haarlem

amasyd the duke verye mooche too spend the floures of of the garysons of naples mylen and lombardye whiche the expence of so manie yeres in the warrs the admyracion of theyr galontness in saruis had poorchesyd.

Morgan knows that the Spanish were masters of battle tactics on land. The Swiss introduced fighting squares, which the Spanish adapted and called tercios, a formation most armies used by 1570. At the end of the 16th century Dutch soldiers generally followed Spanish custom of forming companies of around 150 pike men. Morgan describes these formations in most of his illustrations (figure 20). Pikemen are shown very close together but they actually stood far enough apart to be able to handle their weapons with around 3 feet and 7 feet between rank and file. Pikes were usually 6 yards long, made of ash with an iron spearhead, though the Landsknechts used slightly shorter pikes. They are shown in Morgan's figures as a solid mass of men because the push of pike worked only when all pikemen fought as one; any wavering and the enemy could find a way through. This figure shows five companies in the Spanish camp and one in the Walloon camp. Normally a tercio included pikes, arquebusiers and cavalry. The cavalry was made up of lances placed in four ranks. Each lance consisted of a man at arms and about 5 other horses. The guns used were arquebuses and calivers with a few unwieldy muskets, each firearm with its different problems, wetness being one of the most serious, especially for cannons, which, when they didn't overheat, became stuck in marshland11. Foot soldiers who were not pikemen carried a two-handed sword and a halberd. Dutch soldiers tended to use firearms more than the Spanish because much of the terrain was unsuited to the push of pike or to cavalry charges. As an example of the men Morgan might have commanded, Captain George Gascoigne led 20 halberdiers, 10 bowmen and 101 calivermen. When he left England, Captain Thomas Morgan's company numbered 300-400, one of whom was Walter Morgan.

A tercio was made up of three to fifteen companies or ensigns. Morgan notes in his description of Goes that Mondragon marched with "xi enseygnes three hondred too an enseygne". Each tercio was named after the territory most of the men came from so, for instance, there are the tercio Lombardia and tercio Cerdeña. Each company of pikes could be enclosed by archers or cavalry or firearms. They usually went into battle with archers or arquebusiers as wing men and Morgan shows this in the siege of Mons where a company of pikes is preceded by artillery which at Mons is being fired point blank at the cavalry opposite (figure 24). Most cavalrymen carried a light lance or pistol or a pistol and rapier or a light lance and a rapier. Each company was led by a captain and Walter Morgan and George Gascoigne were captains of companies under Sir Humphrey Gilbert.

At this period there was a new emphasis on military units but the maverick soldier still held sway12. Company cohesion as well as individual pride at being part of a group of like- minded brave men is clear in Morgan's illustrations because he shows both. Shakespeare describes this double identity in Henry's speech before Harfleur, writing "let us swear That you are worth your breeding", a sentiment aimed at gentlemen which encompasses all his soldiers. Henry calls on his soldiers' respect for personal reputation when exhorting them to fight for their country:

On, on, you noblest English.

Whose blood is fet from fathers of war-proof!

Fathers that, like so many Alexanders,

Have in these parts from morn till even fought

And sheathed their swords for lack of argument:

Dishonour not your mothers; now attest

That those whom you call'd fathers did beget you.13

Even with the new importance of fighting in units for country rather than for overlord, it is sometimes hard to tell who is fighting whom in Morgan's pictures even though commanding personalities are often drawn larger than life, Alba, Mondragon, Orange for instance. Thankfully Morgan often adds names to these soldiers as in the drawing of the siege of Mons where the Duke of Alba and the Prince of Orange join battle. The detail in figure 24, the siege of Mons, shows the Prince of Orange, Lord Drunen and von Mandersloo with names written over them. In figure 26 Alba is shown on a rearing white stallion, in a pose which echoes Titian's representation of Charles V painted in celebration of the Battle of Mühlberg when the Protestants were defeated in 1547 so for this design to represent Alba was appropriate. Alba is also shown enlarged directing the sack, or "morder" of Naarden (figure 21) and it is likely that Morgan copied Hogenberg's picture of the sack of Naarden with Alba mounted. It is almost as though there was an Alba seal. At Naarden, Alba looks on as his soldiers create havoc, killing women and children as well as the garrison; a woman begs for life while a man reaches for a baby's ankle (figure 21). Hogenberg's sack of Naarden also shows Alba on the same horse but from behind and, like Morgan's depiction, larger than life. The same cavalier, though without ostrich plumes on his helmet, is shown on almost exactly the same horse, with, amusingly, two raised hooves, each with the same trappings, rider in full armour, facing the same way three times at the sack of Haarlem, one of which is placed, seemingly floating in the air, just in front of a cart offloading bodies ready to be thrown into the Spaarne (figure 22).

Confusingly, both sides appear to carry not just similar arms but also colours. On further examination, this effect is because a push of pike or melée is being drawn. In Morgan's figures Northern Dutch provinces flew Orange's orange, white and blue colours in stripes while Count Bossu's flag was a gold bend dexter on red. Spanish Habsburg colours were, or could be, red bends on a yellow background but were more often a ragged saltire, or both. English soldiers sent to the Low Countries in 1556 tended to wear blue, as did the Scots later in the century. Along with the profusion of colours flown, pikemen, cavalry and arquebusiers added their own colours and they also had their own shape of flag so infantry carried a six foot square standard, lancers carried long swallow-tailed flags, the cavalry had small square standards while commanders were accompanied by their own standards. Each tercio carried its own normally small square flag, if Spanish then usually a red saltire raguly, often on a yellow ground, reflecting the Habsburg coat of arms (figure 14). All these variations can be seen in Morgan's maps.

There is a portrait by Remigius Hogenberg showing Lumey de la Marc on April 1st 1572 after the Beggars took Brill. He wears a padded white surcoat with arms, probably over body armour, and red troos. On the ground by him are his shield, a red lion with red and white squares on a gold ground and next to the shield are his ostrich-feathered helmet and his gauntlets. He holds a spear and a sword is in his belt to his left with a dagger to his right. Morgan shows both Mandersloo and Romero and of course Alba, with plumed helmets (figures 24, 26, 27). The Beggars mostly wore grey with an orange sash. Any colours worn would have been the scarves, shirts or tunics. Soldiers under Parma (Philip II's governor from 1578-92), so probably under Alba too, occasionally wore their white shirts over their armour to be recognised, especially at night. In 1575 some undercover agents wore crimson sashes so the Spanish would recognise them. These people were locals paid by Spain who fired Protestant villages to distract villagers from manning the dikes and bridges14.

The ships' ensigns Morgan shows for the armada were red on white saltires; most 16th and early 17th century depictions of the armada show ships flying these same saltires, see, for instance, the Woburn Abbey version of Elizabeth's Armada portrait. When Alba marched along the Spanish Road into the Netherlands in 1567 he passed through northern Italy, Switzerland and Burgundy and more colours were probably added to his army. There are a few clear flags with saltires in the siege of Mons. Flying in Mons itself there are clear orange white and blue striped flags but there are similar striped standards and saltires. This is one example of the flags showing that armies were clashing in a melée. Morgan's fabulous picture of the naval battle at Horne shows both the Prince's and the King's flags (figure 32).

Occasionally a Landsknecht or Reiter, who could be employed by either side or by a town, is shown with flamboyant clothing, split troos and large feathers in their caps. A good example of this is in the sack of Rotterdam where it appears that a wealthy family follows a mercenary with feathered cap and baggy slashed troos (figure 23). German mercenaries were not known for running away though neither did they like to be penned in by a siege, as Morgan writes of them at Alkmaar. The bravery if not bravado of mercenaries was displayed for all to see by their style of clothing; their clothing got them attention if nothing else. They were normally pikemen though this soldier seems to carry a mace.

Alba is named and shown in a white ruff (figure 26); only the Spanish wore ruffs to battle. Alba's colours were blue on white but he is usually painted wearing a red sash. Alba's army polished their armour to protect it, decorated and gilded it. Williams describes the soldiers at Haarlem advancing "with Drummes, Trumpets and glistering armours" (Williams, p. 126). The parade armour dated 1575 and worn by Parma, a Governor after Alba's departure, looks very like the armour of Henry VIII now in the Tower. The Dutch tended to blacken their armour with ashes and linseed oil but neither can be discerned in Morgan's figures. Of course battle once joined was a confusion and soldiers needed to be able to see the colours of their leaders.

Added to the confusion of battle at Goes is Morgan's position in the vanguard so it is hardly surprising that it is often hard now to tell which soldier is fighting for whom in this battle. Williams comments on the siege of Goes that once Mondragon arrived he managed to invade the town:

Mondragon tooke his march towards Tergoose, having intelligence of the towne: and beeing in sight, the towne sallied and entered into hotte skirmish with our guardes, on the side from their succours: In such sort, that the most of our Campe made head towards them. While we were in hot skirmish with the garrison, Mondragon passed his men through the towne pel mel with ours: ... Wherefore our disorder was great ...(Williams, p. 120)

Details of an army's organization are shown throughout but the drawings of the siege of Zutphen (figure 28) and of Roermond show victualling in process in detail as the battle is being fought. Cauldrons heat while men rest in their tents or on the ground and just the other side of the river, where swans glide, other men fight and die. Hogenburg's map of Zutphen also shows cooking while a phalanx of soldiers races over the bridge to the main gates and drummers sound the attack; canons fire and the town is as yet unscathed while swans float on the Ij and townsfolk run for their lives from one of the town gates. Swans also circle the towns in the sacks of Rotterdam and Naarden as townsfolk and country dwellers try to flee from pillage inside the town walls15.

The expedition of Sir, later Colonel, Humphrey Gilbert's and Captain Thomas Morgan's companies into the Netherlands was joined principally for mercenary reasons, to make a living, but it was also seen as a soldier's training ground. For example, Roger Williams writes that seasoned armies function like "an universitie" (Williams, p. 27). In 1586 about a third of the soldiers fighting for the Prince of Orange, 12,000 men, were from Britain.16 However between 1574 and 1578 the Dutch only reluctantly allowed the English to fight with them because of their reprehensible behaviour. They were considered cowardly and unprofessional. They in turn openly despised the Dutch, whose freedom they were after all fighting for. In his lines about the Flushing frays, Gascoigne calls them variously treasonous, robbers, "the drunken dutch, the cankred churles" whose "braynes with double beere are lynde" and so on17.

Of Captain Walter Morgan's reasons for joining the expedition little is known for the moment bar his own texts. According to Williams he was indeed courageous soldier. Both Morgan and Williams describe the siege of Goes in detail. Morgan describes how the Prince of Orange's man Jerome T'seraerts entrenched before the town and then sent for battering pieces which took three days to arrive, along with two thousand landsknechts and "iii canons and a collveringe and plasyd them [added with caret] in the chappell platte afor the chyffe gate of the toune as by the figure ys desscribed". They are drawn by Morgan carrying muskets, crossbows, lances and pikes, among the salt hills, attacking what looks like an impregnable defense, "a peece of fortificacion" Morgan calls it, climbing scaling ladders (figure 30). Williams writes of the same siege, that the fighting was heavy and finally, he writes

For I perswade my selfe, the most of them were afraid. I am to blame to iudge their minds; but let me speake troth. I doe assure you, it was not without reason; for the most of us who entred with Yorke were slaine; such as escaped, swam, and struggled through muddy ditches(Williams, pp. 112-13)

Walter Morgan was wounded while "Captaines Bouser, Bedes, and Bostocke English" were killed, Williams writes, "besides Walloons and French which served most valiantly. But the chiefe praise next unto God, ought to bee given to the English Ensignes and armed men. Captaine Walter Morgan served very well; who was overthrowne with a musket shot in the head of the armed men. All the rest did most valiantly" (Williams, p. 116). Gascoigne too describes the scene: "I was againe in trench before Tergoes," he writes and agrees with Williams about the bravery of the attack of Goes and suggests that they were a hot-headed lot:

Yet surely this withouten bragge or boast,

Our English bloudes did there full many a deede,

Which may be chronicled in every coaste,

For bold attempts, and well it was agreed,

That had their heads be ruled by warie heede,

Some other feate had bene attempted then,

To shew their force like worthie English men.18

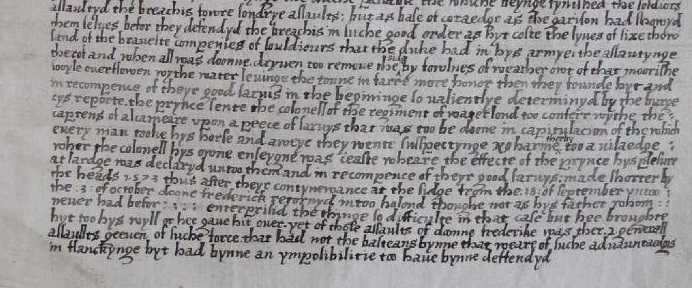

What does Morgan write about Goes? He does not mention being wounded. The illustration is very careful (figure 30). The turrets are easily picked out and the salt hills, which Morgan also calls salt houses, are marked with text. Gilbert's men, who included Gascoigne, are drawn large, swarming up the hill they've created, while guns fire from the walls and cannon relentlessly beat on town's defences. A phalanx of Landsknechts are seen arriving with massed lances and pikes and lances edge the battlements like porcupine quills. Morgan agreed that the attack was rash and writes that Gilbert, their Colonel, who rose from his sickbed when he heard of the unsanctioned exploits of his men, thought the whole affair, "thys stolen peese of sarvis", impossible to achieve:

syrr umphrey gillbertt theyr coronell was not [not is added with a caret] ther whom was too geeve his consent thorowe advisemente in anye mater of ymportaunce.the other was that the peece beynge taken wiche was not too be doonne wytheowte greate losse of men in : the esscale by reason that the vamure was not dissmembryd. was too be comaundid by smalle towretts that over lookte hyt beynge taken: syrr umphrey gillbert beynge in flooshinge at the physike for hys fever. heeringe of thys stolen peese of saruis pretendyd in hys absens.forgott hys sickness alltogether [alltogether added with a caret] in hys expedycion made too come thyther. wheruppon hee was : made pryveye therof at hys commynge and requestyd theruntoo.whiche in woords hee utterlye refusyd uppon intelygencys that was geeven hym of the evyll provigions of laders the flanckynge placys and vamures not beten doune : : soundinge in reason an ympocybylitye too doo anye good therin : yet all thes woords and knowledge of dificullties all for. in thys exployte. too showe hys resolucion therby too avoyde suspecte. that hyt was not cowardlynes that causyd hym too gaynesaye thys enterprise hee was the formoste man on the laders that putt thys exployte in execucion ...19

We know Morgan was present at least at one of the actions in and around the Drowned Land and Haarlem Mere because Williams mentions him. He is at least as adept at depicting, or copying, naval as he was land skirmishes. At the time of the taking of Rammekens, Colonel Morgan's regiment was striking for pay and demanded to be sent back to England, but some of his men continued to fight for the Prince:

Notwithstanding divers Gentlemen of that regiment accompanied Mounsieur de Poyet; amongst other Captaine Walter Morgan, Master Christopher Carlell and Master Anthonie Fant ... Poyet advanced his forces on the Ramkins dyke, towards Middleburgh. Being arrived right against the enemies guards at the head, ours intrenched themselves in that place; lodging our forces on the dyke, from the Ramkins to the said first guarde: having betwixt us and the enemie the haven, which might bee some threescore broad; where wee had divers good skirmishes, as well by those that sallied from Middleburgh, as by them that lodged at the head(Williams, p. 148)

Sieges

Most of the sieges Morgan describes are against towns or villages (in Williams' description, for example The Hague was a village). Most coastal villages had their own dialects and their own government and were largely independent of each other. Zeeland, where many of the actions in Morgan's work took place, very much survived separately from the other Low Countries, even Holland, with a poorly developed sense of national identity. Any governor offering freedom of religion and low taxes would suit them; any who did not would be unwelcome. Haarlem had 18,000 inhabitants and was besieged by Alba's son, Don Frederick, for seven months before the town fell. When Frederick took Haarlem, 2,300 were killed according to Motley. Blockades described by Morgan take place mostly in the approaches to Antwerp, which was a major European port.

The wars in the Netherlands were mainly siege warfare, which both sides had experienced, the Spanish from their Mediterranean wars, St Elmo, Malta (1565) and Famagusta, Cyprus (1571) for instance. Besieging, tunnelling, trench warfare, climbing ladders to attack, mining walls, building platforms, all were imagined by the English to be their forte but all European countries were well versed in siege warfare. Morgan praises Alba's siege of Mons, however, and does not suggest the English could have done better. "The Duke of Allva in person besydgde the toune and hadd entrenchte hym sellfe so forcesiblie therabout too the rhiver side that his campe in force was not moche inferior too the stregth of the toune thoughe lesse in comoditie."

Williams comments that even were the enemy three days march away, the first thing he did was to order deep trenches (Williams, p. 90). Sometimes "a forced hill" was "made with mens hands" as Williams says (Williams, p. 102) to give the besiegers advantage. Morgan describes the same hill at Goes: "they tooke another enterprise in hande. whiche was the attemptinge of a peece of :: fortificacion that they byllte wythe owte the toune joyninge too the walle too flanke all the weakest parte of that side of the toune that they encampte before." Once an attack on a town failed and a siege begun, focus was on supply lines which, in the coastal regions of Holland, usually meant shipping.

Often suburbs were destroyed either by the town besieged to prevent attackers taking cover or by attackers to give them a clear target. Morgan describes and figures salt hills fired to prevent besiegers at Goes: "wheare the garison persevinge greater forcys then they weare of abilitie too withestand.in dowpte of the besydginge of the toune putt theyr suburbes a fyre. whiche for the moste parte weare sallte howsys that they sholde not : so comodiouslye encampe in drye howsys so neere theyr wall." (figure 30).

Morgan's description of a couple of days besieging Goes gives a good idea of what was involved. They took:

iii canons and a collveringe and plasyd them [them added with a caret] in the chappell platte afor the chyffe gate of the toune as by the figure ys described. wheare they began too batter the corten by the gate ii daes toogether or they founde the difficulltie too make a breache ther then bente they theyr artilerye on the gate disscoveringe small good too be donne in the other place and applyed theyr batterie contynewallye all the daeye tyme theruppon tyll hyt was verye neer sautable

This initial siege of Goes failed and it was following this that Gilbert's ill-fated camisado was attempted quickly followed by Bartel Entes and his 2000 Landsknechts which attack also failed, a failure blamed by the Landsknechts on Jerome Tseraarts, which name Morgan transcribes as "serace".

but as befor when hyt was allmoste sautable ther was no more booletts too be had and the lanskynghts roonnynge upp too the tope of the breache seynge the weye too greate too leape doune cryed owte on serace thorowe the campe as a traytor when they sawe hyt so.neere sautable and so : : easye to be doonne for wantynge that that shollde fynishe hit : wheruuppon for hys saftye hee departyd aweye in too holande too the prynce too cleere hym sellfe of thys acusacion

Along with pikes, swords, firearms and bows there were rolling trenches. Williams describes them as skonces which held "at the least three hundred men", made of boards and horse- drawn which ran on wheels with openings every five to ten paces "as pleased our Enginer"20. Gascoigne also mentions the rolling trench which is illustrated by Morgan (see figure 5). He writes

I was in rolling trench,

At Ramykins, where little shotte was spent,

For gold and groates their matches still did quenche,

Which kept the Forte, and forth at last they went,

So pinde for hunger (almost tenne dayes pent)

That men could see no wrincles in their faces,

Their pouder packt in caves and privie places.21

Rolling trenches were dug with many curves, like a worm. Trench warfare would normally be fought only with firearms but rolling trenches made it possible to move from one part of the field to another with many vantage points from which to attack. Sieges in the Netherlands could last for months. Williams describes "our ignorant poor siege" of Goes, for instance, lasted from August till October. We hear from Morgan a soldier's constant complaint, one which Williams also makes, that ammunition had run out but this was only one reason why sieges could last so long. The siege of Haarlem lasted for seven months. Middelburg and Flushing seemed to be under constant threat, standing on the Scheldt, the trading route to Antwerp.

Some towns were well supplied but some broke dykes to create supply routes. Morgan explains that after the St Bartholomew's Day massacre the promise of fifteen thousand Huguenot soldiers could no longer be kept so the Prince abandoned the battlefield at Mons and ordered his brother Ludovick to reach terms with Alba. Mons was well "storyd wythe monyshion: and fornyshed wythe good soldiours in : : suche wyse that they weare well assuryd that hyt sholde coste manye a broken pate before hyt sholde be woone" and so the Duke agreed to terms with Ludovick. Alba allowed Mons to surrender with all townsfolk and Ludovick allowed to leave unmolested, only the garrison punished (figure 29).

Reinforcing towns continued throughout the wars in the Low Countries. Indeed Rammekens was built defensively in 1547 by Charles V using an Italian engineer (figure 5 shows Charles V's fort on the Scheldt). Old town ramparts could not withstand cannonades so they were reinforced by earth strengthened by stone bastions using the Italian method of pointed rather than rounded defences. Morgan's illustrations show both older and newer defensive ramparts.

Siege warfare was in many ways Alba's downfall because while he excelled at traditional battles in traditional battlefields, he could not use his soldiers the same way on marshy ground, crisscrossed by streams and woods and scattered with fortified towns. Orange learned fast that trench warfare and scattered firepower was more effective than full scale battles in his coastal territories; his soldiers lacked the control Spanish tercios had learned on the plains of Italy and Spain. His men scattered when faced with massed companies of pikes moving as one but his forces had more guns than the Spanish. It was probably at Mons, between 12th and 18th August 1572, that the Dutch realised that battles against the Spanish were no longer an option. Morgan describes the battle for Mons where Ludovick of Nassau, Orange's brother, was under attack (figure 24). The Prince and his advisers cut off Alba's supplies to force him to fight in the trenches but his infantry refused to be separated from the cavalry, still thinking the only way to defeat the Duke was in full battle. Meanwhile the Duke proved his "supptilitie of [of added with caret] wytte" and ordered trenches to be built at a distance, quietly, at night, not a musket's shot from the Prince's camp. Alba whose plan was "never too hasarde anye thinge on the hands of fortune" sent out Romero as a decoy in the morning and the Dutch believed battle was about to begin. The Prince, Mandersloo and Drunen charged with their men at Romero, their Reiters charging after Romero and right into the Duke's new trenches. Four or five hundred horsemen were killed and the Prince realised that without the strength of the Huguenots he could not win Mons in traditional battle.

Confusion about how to fight in the marshy country continued. The battle for Haarlem was lost because Battenberg, the Prince's commander, was incompetent, not because he was a dishonourable coward; he had not realised that warfare around the coast could not be large battles. From Williams' account, Gilbert's followers, along with Morgan, arrived before Battenberg's shameful retreat so Morgan writes from experience. Williams writes "Thus were wee ouerthrowen with ill directions and ignorant government." (Williams, p. 130). Morgan agrees saying that "Harlem the metrapolitan toune of that countey" was lost partly because Batenboorke was in charge, "a man of so base a capasitie in hys direccions as Counte Battenboork" that "hys directions resspectynge not the losse of grounde" meant the Spanish broke Haarlem's access to victualling even though the Dutch had mastery of the sea.

During Morgan's time in the Netherlands sieges of coastal towns were usually broken by shipping delivering supplies. After the battle of Haarlemere, and the breaking of a dyke, Haarlem was completely surrounded and fell to the Spanish. This battle was the only naval action lost to the Spanish and after this the Dutch navy continued to increase in strength until they had mastery of the wealthy trading ports of Holland and Zeeland. Morgan writes of Alba's shipps: "the duke beynge contynewallye overmatched allweys by the prynce on : the water harlem meare exeptyd"22. Gascoigne confirms that Middelburg was under siege the whole period of Morgan's service.

The force of Flaunders, Brabant, Geldres, Fryze, Henault, Artoys, Lyegeland, and Luxembrough, Were all ybent, to bryng in new supplies To Myddleburgh: and little all enough, For why the Gæulx would neyther bend nor bough.23

The navy was funded by sea blockades to exact goods and money from trading vessels and from privateering which funded the repair or building of ships. Once Veere was taken in May 1572, the Beggars had a well-equipped naval yard. Meanwhile the Spanish armada lacked easily manoeuvrable ships and experience in shallow waters so found it hard to break Beggar blockades to free supply lines.

Reputation

Who is brave in this tract? In the dedication, Morgan calls the main players in this game "perssons of credite". If any soldier is presented as noble it is the Prince of Orange, whom Gilbert, Gascoigne and Williams equally respected. Not all the Dutch protestant contingent is described with respect. The Calvinist Count Lumey de la Mark, "a noble gentyllman of coraedge accountyd hardie", leads not a troop of brave sailors but band of "fugitives" known in England for their piratical attacks on English ships of trade and thus evicted by Elizabeth II in late 1571, early 1572.24 He was feared in Brill after he sacked the town in 1572 so Morgan's "hardie" is one way describing him. In time these fugitives, the Sea Beggars, would be the mainstay and saviour of the Protestant republic.

Morgan presents Alba as "beynge wylye" but Alba's image is given precedence often enough in Morgan's illustrations to show that as a man of war if not as governor, he was respected; admired as a tactician if not as a human being. His lieutenant Julian Romero, however, is more reckless than prudent. At the siege of Mons Alba, like Romero, is seen facing the enemy while his pikemen and arquebusiers are forced back by Orange's pikemen and arquebusiers; halberdiers run between companies. Lord Drunen and von Mandersloo are shown on stallions and Orange on a mare along with two squadrons of Landsknechts. Lord Drunen and 4 or 500 horsemen were slain, writes Morgan, and his figure indeed shows Drunen hit and collapsing backwards over his horse (figure 24). Charles Oman describes this action:

Morgan has chosen to introduce into his picture of the retreat from Mons the one episode of actual fighting which occurred, during the operations of this abortive relief. On September 12th a single Spanish regiment, under Don Julian Romero, executed at dawn a daring raid into the Prince's camp -- which they surprised, cutting down the sentinels and penetrating as far as William's own tent, from which the Prince escaped in haste -- his master-of-the-horse and secretary were actually killed. Romero then turned back to re-enter the Spanish lines, but had to cut his way through the enemy's cavalry, who were hastily getting under arms. This he did, with some loss, but much less than he had inflicted on the Prince's army.25

Alba, though a cunning tactician is also shown to be a murderer of 3000 townspeople and defenders at Naarden. He is subtle, a "tyranous spaniarde" and a wily fox. His tactics at Mons, building trenches in the night and leading his enemy into an ambush the next day, are typical of his schemes. At Naarden, however, he had no need to scheme. The town literally gave itself up to murder and plunder as Morgan delares in his preface to his text:

the horible morder at narden doonne by the duke

of allva beyinge recevyd intoo the toune in hys

comynge from zuytphan too harlom whom

putt all the inhabitaunts thereof too :

the swoorde man woman and :

chyllde the. 30. november 1572

Mondragon was generally admired for bravery as well as inventiveness especially when relieving Goes by marching a regiment of footmen through the shallow sea, where Orange's ships could not sail thereby achieving a feat "unhard of befor". This event allows Williams to accuse his captains of sluggishness because, he writes, Mondragon could have been overcome while resting after the sea crossing before taking Goes. Morgan agrees and writes that an ensign of 200 landsknechts who had been left as a guard simply abandoned their position, allowing Mondragon's tired soldiers to reach dry land and rest.

Violent acts were always committed by fighters during normal warfare, or as Williams writes "There can bee no braue encounter without men slaine of both sides." (Williams, p. 116). The Spanish fury and the Beggars' brutality stand out. What does Morgan do about the negative stereotypes of soldiers' reputations? He is happy to condemn the Spanish but skates over Dutch and certainly English plundering. He fails to mention how large a contingent of Englishmen followed the Prince and how many at the least profited by plunder or were, as Gascoigne puts it is "armed with avarice always" (Dulce Bellum Inexpertis Est, stanza 68). For instance Morgan describes the Beggars under Lumey de la Mark attacking Brill, which the townspeople try to defend. The attack turns into a slaughter the kind of which is described and pictured in detail in Naarden and Rotterdam but Morgan says simply

counte marke callde too the gonners too geeue fyre wythe an unserten nomber of teribyll othes shakinge hys swoorde uppon them in threttnynge that they sholde fynde no more mercye at hys hands then doggs after that somnaunce for so mooch as they hadd not the grace to consyder the benefitt thereof too be the welthe of the whole country.: in whiche furie hee comaundid hys soldiours withe toorffe and strawe too sett the gate a fire , the whyche grewe too suche a smoke and flame that the poore boorgessis thought that the /// worlde hadd bynn at an end withe them whiche was the full time of repentaunce in whiche feare the yeldid them sellves and theyr toune in too hys hands too use hys wyll wythe all the fyrste of aprell 157 2

The memory of the atrocities committed by Lumey and the Beggars in 1572 is sharp still when Gasciogne sails to the Brill in 1573. The townsfolk were loath to let the ship in thinking that they too would plunder and pillage. He writes

Now ply thee pen, and painte the foule despite

Of drunken Dutchmen standing there even still,

For whom we came in their cause for to fights,

For whom we came their state for to defende,

For whom we came as friends to grieve their foes

They now disdaynd (in this distresse) to lend

One helping boate for to asswage our woes ...26

Alba's fearsome reputation would have been known to Captain Thomas Morgan's and Sir Humfrey Gilbert's contingents of soldiers from his Catholic Council of Troubles, which condemned to death Protestant leaders of the Dutch rebellion as heretics, with which Morgan begins his treatise, and also that one of Alba's monikers was de IJzeren Hertog, the Iron Duke, because of his unbending cruelty in 1572-3. This cruelty partly inspired the description la leyenda negra, the black legend, a term which describes specifically Spanish brutality. The term normally describes exaggerated stories of atrocities but in this case Alba's command deserved the description. Williams writes that Alba promised "to his Captaines and souldiers, that the spoile of Holland shold be theirs, upon condition they would execute all they found"27. That Philip II equated the revolt in the Netherlands with heresy gave him licence to punish with severity. His cruelty was not unique to the times, vide Elizabeth I executing Catholic heretics for treason, especially after her excommunication in 1570; however, the cruelty of Philip II's army is striking. Pieter Bruegel the Elder painted his Massacre of the Innocents in 1565-7, the year Alba became Governor, with Herod's soldiers now Philip II's, painted when Alba was Governor, the scene painted again by Bruegel's son28. Bruegel, based in Mechelen, Antwerp and then Brussels when the centre of power moved from Mechelen to Brussels, also painted The Triumph of Death in 1562 which shows skeleton soldiers laying waste to a blackened land, inhabitants fleeing and an auto da fe in the background, so the Low Countries were used to a violent occupation. Alba's son, Don Frederick, followed suit when he forced captives from Haarlem to dig offensive positions at Alkmaar, ignoring their pleas for mercy by offering them a death in honourable service to Spain rather than by hanging.29 The citizens of Haarlem, Morgan writes,

crauyd compasion at doone frederiks hands who aunsweryd them that hyt was farr more honorable for them too dye in so : noble a peese of sarvis as that was lyke men then too be stranglyd uppon a gibett lyke doggs acordynge too theyre deserts for theyr ofencyss comitted whiche was never too be forgeeven. by whiche : : martyrdome they weare forcyd too fynishe the same theyr slaughter therin respectyd no more then yf they had byne turks in makynge the ditche passable the whiche beynge fynished the soldiors assaultyd the breachis fowre sondrye assaults: ...

The citizens of Haarlem knew what an honourable death at the hands of Frederick's men meant. Peter Geyl writes about Frederick's investiture of Haarlem, "Don Frederick decided to try moderation this time, and the citizens' lives were spared. Five executioners were nevertheless set to work on the soldiers, and finally, when arms had grown too tired to wield the sword, those that remained were thrown, bound back to back, into the river Spaarne."30

Morgan took part in naval actions as well as on land. In both, he represents rebel forces as more merciful than the King's but the rebels also needed to pay their soldiers and intercepting foreign trading ships to demand tax was one way of funding to "release the countreye from bondaege" as Morgan writes, and the many battles around Rammekens were both to take Middelburg and to make money. Williams describes one of the skirmishes near Rammekens, dated 3rd April 1573:

The enemy perceiving our resolution, fell in rout before the winde, with all the sailes they could make, to recover the river of Antwerpe. Notwithstanding, wee tooke, burnt, and forced to runne on the sands, above two and thirty sailes; & returned victorious, with their vice-Admirall, rere-Admirall, and divers others in to our towne of Camfier: where we filled our prisons with Spaniards, Walloons, and great numbers of their marriners.

Morgan describes how in the same battle, Rammekens, on 3rd April 1573, twenty-two great ships of the Spanish armada reached safety - or so they thought - under Charles V's new fort. Morgan tells this piece of service to praise the bravery and foresight of Captain Worst but it is the rebels' reputation for cruelty to captured men which stands out. The armada had to be attacked but the seas were not navigable and Worst waited and waited for the water to rise, every minute seeming to be an hour:

passinge awey the daeye nyghte drewe on whiche in spendinge the tyme or the tyde cam in as hit fell then.capten woorste beynge weried therwythe by desire too se the triall of this matter thoughte everye houre a monthe tyll wooord was broughte hym : that the floodde sarved

At last the sea was high enough and after reconnoitring among the Spanish ships in a pinnace with a dozen oars, he called the drums and trumpets to sound a charge. Morgan berates the Spanish for not even bothering to stand sentries. The Spanish panic because "they knewe righte well ther was no mersie too be founde at the floushingers hands [hands added with caret] yf they weare overcomd:".

Some of the armada were such huge ships, built so high, that they could not be boarded so they were fired with burning trunks of wood. Figure 33 shows one of the Spanish battleships sinking as it is attacked by Dutch hoys and battleships.

Morgan clearly knew a great deal about Worst so it is interesting that he depicts him as brave and moral and fails to mention the cruelty he showed towards Pedro Pacheco, Alba's governor of Flushing, although admittedly this event happened a few days before Morgan arrived at Rammekens. It is worth quoting this section from Williams because it confirms the theory that Morgan did a certain amount of whitewashing for Lord Burghley. According to Williams, Vorst and other Flushingers refused to accept Pacheco as Governor and carried:

Seignior Pacheco to the gallowes; where they hung Duke d'Alvaes Scutchion, at which they hanged Pacheco, with his Commission about his necke; although Pacheco offered them assurance of tenne thousand Duckets to have his head struck off. They hanged also some five and twenty of his followers; beating them with stones and cudgels all the way as they passed to the gallows(Williams, pp. 99-100)

Alba retired in December 1573 and Luis de Requesens took over as Governor. Alba had failed Philip II; his harsh punishments turned Dutch towns against him rather than frightening them into submission but Morgan displays respect and understanding of his enemy when he writes in his fluid prose that Alba, though "so suptyll a foxe", is unable to wade through the toiling turmoil of civil war in his old age. Spain was close to bankruptcy by 1572, bankrupt by 1575, and its soldiers had not been paid so they mutinied. Plunder was one way the soldiers could be rewarded. Economics and religion again.